Jackson School Rapid Response Mission Continues Collecting Data from Seabed to Study Impacts of Hurricane Harvey

September 28, 2017

By Monica Kortsha

Jackson School Science Writer

This post is second in a series documenting the Jackson School of Geoscience’s Rapid Response mission to study the coastal impacts of Hurricane Harvey. Read the first post here.

Portland, Texas – The Jackson School’s Rapid Response team started its Tuesday by transporting their “baby CHIRP”—a miniaturized seabed scanning sonar device— from the bed of a pickup truck to their boat, the Research Vessel Scott Petty, stationed at the Bahia Marine in Ingleside, Texas.

Although they call it the “baby,” it still weighs 150 pounds. A Texas State Trooper stationed at the marina lent a hand lifting the device off the truck, and was quick to recognize the importance of the research team’s survey of the seafloor off Port Aransas in the wake of Hurricane Harvey. He suspected that the hurricane surge shifted the sediment on the seafloor, and that navigation maps may need to be updated for fishing boats and barges.

It’s a plausible scenario. Part of the team’s mission is to collect the hard evidence to see if change occurred, and if so, seek to explain the processes behind it. The researchers are aided by survey data collected in 2009 and 2012 by the Marine Geology & Geophysics undergraduate field camp course, which will serve as a “baseline” of the seafloor setting.

If the research does find significant changes in sediment distribution, a short term benefit could indeed be improved navigation maps. But the team primarily has the long view in mind. They’re hoping that by understanding how sediments change along the seafloor after a hurricane, they can improve predictions on how storms move sediments and how that impacts beaches and barrier islands along the Texas Gulf Coast. Understanding these issues is vitally important to vulnerable coastal communities and infrastructure, which depend on barrier islands and dunes for protection from storms like Harvey.

John Goff, a senior research scientist at the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics (UTIG), even envisions data on sediment movement one day being incorporated into computer models used to understand a hurricane’s impact.

But before they can do any of that, they need the data.

On Sunday and Monday, the team successfully imaged the majority of the Lydia Ann Channel using multibeam and sidescan sonors, two complimentary methods that collect data on seafloor topography. On Tuesday, they started collecting multibeam data on Aransas Bay, the channel directly across from Port Aransas—a city built on a barrier island that was hit particularly hard by Harvey.

From the boat, John Swartz, a Ph.D. student on the mission, pointed out a bluff of bright white sand near the water’s edge. He said that the white sand—free of the grassy vegetation that covered most of the undeveloped part of the island—was a sign of erosion likely caused when the hurricane’s storm surge took sand back into the sea with it. Erosion and deposition of sediments like sand is a constant process on barrier islands. But a hurricane’s storm surge can remove a large amount of sediment in hours and quickly erode vital sand dunes or make other changes to the

island that more gradual natural processes can make worse.

Choppy waters cut the multibeam scanning short Tuesday. And despite happily chirping during test boot-ups both at home and earlier on the boat, baby CHIRP wasn’t working properly when the team deployed it in the water. Still, the researchers managed to have a successful day by focusing on pulling sediment samples from 14 different locations in the Lydia Ann Channel.

The team chose the sampling areas based on data from the multibeam map of the channel’s seafloor generated from surveys on Sunday and Monday. They wanted samples from the most interesting spots, areas patterned by ripples or marked by changes in depth, but also the flat “boring” spots, as well, said Goff.

“You can’t understand interesting if you don’t know boring,” he said.

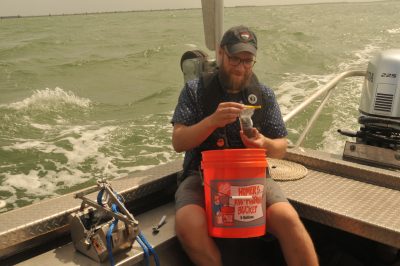

The process involves dropping a spring-loaded metal claw called a “Petite Ponar” off the side of the ship, and rapidly pulling it back up as soon as it snaps sediment up from the seafloor. To the untrained observer, most of the samples looked the same: a slop of grey-brown sand grains. Swartz said that a closer analysis back in the UTIG lab will help determine the grain size composition of the samples, a value that could help with interpreting any observed changes on the seafloor.

One sample included clumps of sand stuck together, a structure that’s associated with very fine-grained material that was rapidly plucked up by a high velocity flow in one area and deposited in another. Swartz said that it is an interesting find, but one that can’t be tied definitively to the hurricane.

“It helps fill in the story on how this tidal channel is working,” Swartz said. “This could happen all the time, or it could be indicative of the storm.”

The team still has two more days of surveying planned, and is hoping they’ll be able to repair baby CHIRP before they head out to sea again on Wednesday. Back at the marina, they cleaned and lubricated the sonar’s parts with the help of a socket wrench lent by Jimmy, a local who lives near the marina and was eager to help out by sharing his tools and the contacts of surveyors he knew.

“Meeting people is one of the nice things about fieldwork,” said Swartz. “You meet people who might have access to potential new data sources you wouldn’t have known about otherwise.”