Texas Serengeti

October 25, 2019

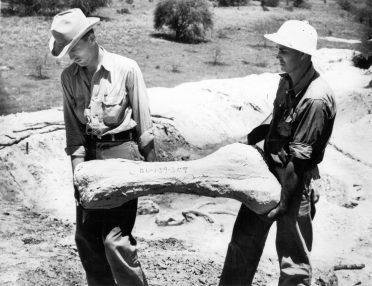

During the Great Depression, some unemployed Texans were put to work as fossil hunters. The workers retrieved tens of thousands of specimens that have been studied in small bits and pieces while stored in the state collections of The University of Texas at Austin for the past 80 years.

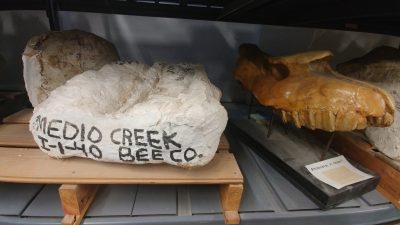

Now, decades after they were first collected, a UT researcher has studied and identified an extensive collection of fossils from dig sites near Beeville, Texas, and found that the fauna make up a veritable “Texas Serengeti” — with specimens including elephant-like animals, rhinos, alligators, antelopes, camels, 12 types of horses and several species of carnivores. In total, the fossil trove contains nearly 4,000 specimens representing 50 animal species, all of which roamed the Texas Gulf Coast 11 million to 12 million years ago.

A paper describing these fossils, their collection history and geologic setting was published April 11, 2019, in the journal Palaeontologia Electronica.

“It’s the most representative collection of life from this time period of Earth history along the Texas Coastal Plain,” said Steven May, the research associate at the UT Jackson School of Geosciences who studied the fossils and authored the paper.

In addition to shedding light on the inhabitants of an ancient Texas ecosystem, the collection is also valuable because of its fossil firsts. They include a new genus of gomphothere, an extinct relative of elephants with a shovel-like lower jaw; the oldest fossils of the American alligator; and an extinct relative of modern dogs.

The fossils came into the university’s collection as part of the State-Wide Paleontologic-Mineralogic Survey that was funded by the Works Progress Administration (WPA), a federal program that provided work to millions of Americans during the Great Depression. From 1939 to 1941, the agency partnered with the UT Bureau of Economic Geology, which supervised the work and organized field units for collecting fossils and minerals across the state.

The survey found and excavated thousands of fossils from across Texas including four dig sites in Bee and Live Oak counties, with the majority of their finds housed in what is now the Texas Vertebrate Paleontology Collections at the Jackson School Museum of Earth History. May’s paper is the first to study the entire fauna.

In order to account for gaps in the collection, May tracked down the original dig sites so he could screen for tiny fossils such as rodent teeth. One of the sites was on a ranch near Beeville owned by John Blackburn. Using aerial photography and notes from the WPA program stored in the university’s archives, May and the research team were able to track down the exact spot of an original dig site.

“We’re thrilled to be a part of something that was started in 1939,” Blackburn said. “It’s been a privilege to work with UT and the team involved, and we hope that the project can help bring additional research opportunities.”

Back to the Newsletter