Birds Reinvent Voice Box in Novel Evolutionary Twist

September 24, 2018

Birds tote around two vocal organs inside their bodies, but only one works.

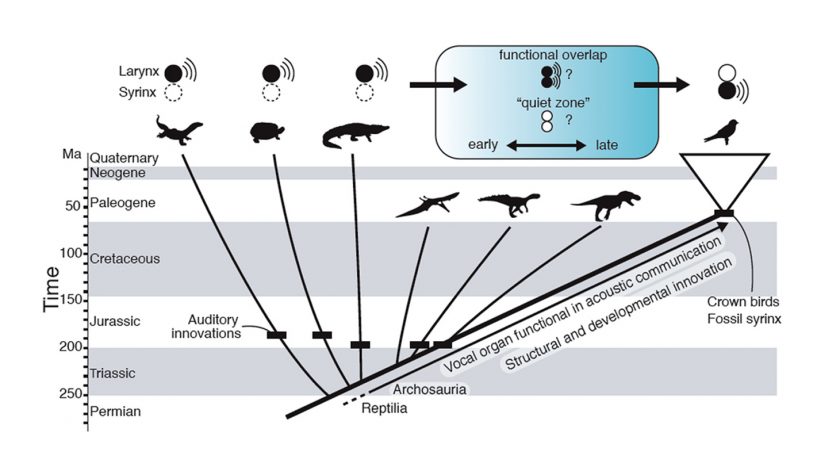

New interdisciplinary research suggests that this distinctly avian anatomy arose because birds, somewhere in their evolutionary history, opted for building a brand new vocal organ — the syrinx — instead of modifying an existing one that is present in an array of animals but silent in birds — the larynx.

The researchers, a team of scientists including developmental biologists, paleontologists and evolutionary biologists, said that the evolution of the syrinx — which is unique to birds — raises questions about changes in bird vocalization over time and can help shed light on the mechanisms driving the development of new structures in animals. The syrinx is an especially interesting case because it is one of the rare instances in which a new structure evolved without serving a new function.

“The syrinx is a kind of novelty that you don’t see commonly in the tree of life,” said lead author and principal investigator Julia Clarke, a professor at The University of Texas at Austin Jackson School of Geosciences. “What’s kind of peculiar about it is that in a lot of biological novelties the structures change in response to a new function, but in this case you have apparently the same function.”

The diverse team, including Evan Kingsley and Cliff Tabin from Harvard Medical School as well as UT affiliates Chad Eliason and Zhiheng Li, published their study in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on Sept. 24.

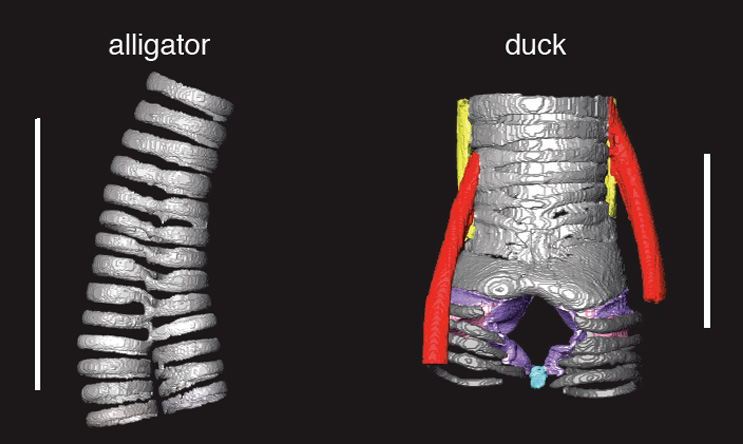

The syrinx sits at the base of the windpipe near the heart in birds. The larynx is located above it within the windpipe. Whereas most land-dwelling animals with a backbone produce sounds with vocal folds within the larynx, birds don’t use it. Instead, birds create calls in the syrinx by passing air over soft tissues supported by cartilaginous rings.

The study investigates how and why birds developed this completely new way of producing sound.

Some animals modify sounds produced by the larynx with the help of other structures. For example, male koalas have vocal folds above their larynx that create deep bellows, and toothed-whales can modify vocal sounds using folds in their nasal cavity.

However, the syrinx of birds stands out because it is a distinct vocal organ that exists alongside another vocal organ. Although the larynx is now defunct in birds, the fact that it’s functional across the animal kingdom presents a possible evolutionary scenario in which the ancestors of living birds may have had two functional vocal organs — a larynx and a syrinx — that sounded together

The researchers also explore an alternate scenario in which the larynx stopped working and the syrinx evolved to give the ancestors of modern birds their voice back.

“Instead of arising as an accompaniment, the syrinx evolved as a replacement noise-maker after the larynx lost its primary sound producing function, ending a potential ‘quiet zone’ in evolutionary history where bird ancestors didn’t make a peep,” said Eliason, a postdoctoral associate at the Field Museum of Natural History and a former Jackson School postdoctoral researcher.

However, the researchers note that the presence of a perfectly functional larynx in the closest living relatives of birds and improvements in hearing in multiple lineages of dinosaurs make the syrinx and larynx functioning together a more likely scenario than the “quiet zone.”

In addition to looking into the evolutionary environment, the team investigated the developmental history of the syrinx in comparison to the larynx.

“Despite their related function, the syrinx and larynx have distinct developmental histories — forming from different tissues,” said Kingsley.

The origin of a unique developmental path and novel bird organ could be linked to other amazing avian innovations — from the dawn of flight to the evolution of complex bird song and the development of long necks in extinct dinosaur ancestors of modern birds.

“What we show about syrinx development suggests fundamental differences from the larynx and has important implications for how the enormous variation we see within birds in song and structure arose,” Kingsley said.

Even though the syrinx may be just for the birds, Clarke said that understanding more about what led to its origin and development could help scientists learn more about how biological innovation works in the big picture.

“When we put this all into the context of biological novelty, we gain insight into how new structures and functions arise in the history of life,” Clarke said.

The research was funded by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.

For more information, contact: Anton Caputo, Jackson School of Geosciences, 512-232-9623; Monica Kortsha, Jackson School of Geosciences, 512-471-2241