PTERODACTYLS AT DUSK

March 27, 2018

Jackson School scientist co-authors a paper reporting seven pterosaur species from the end of the Mesozoic Era

By Brain Andres, Ph.D.

Research Associate

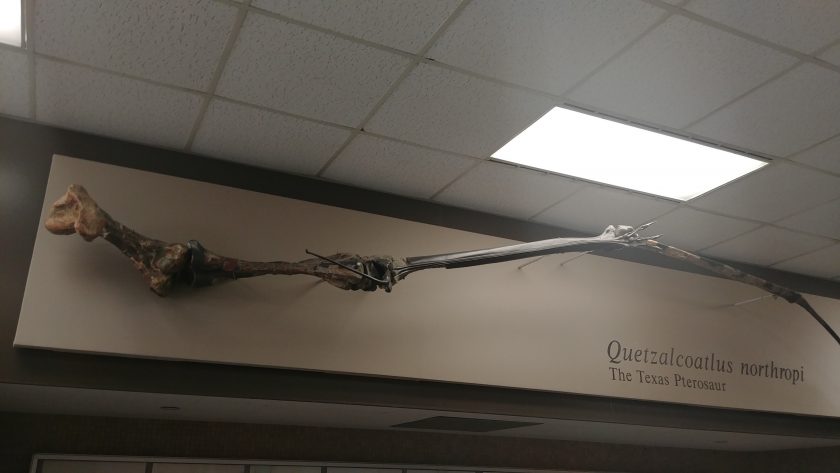

On the ground floor of the Jackson Geological Science Building hangs the giant wing of Quetzalcoatlus.

The label proclaims it as The Texas Pterosaur, and for good reason. Quetzalcoatlus, which hails from the Big Bend region of Texas, is the largest species of pterosaur (and therefore largest flying animal) and the last known pterosaur to live before the extinction event that killed off all pterosaurs and non-avian dinosaurs (a specimen found within inches of the end of the Mesozoic Era).

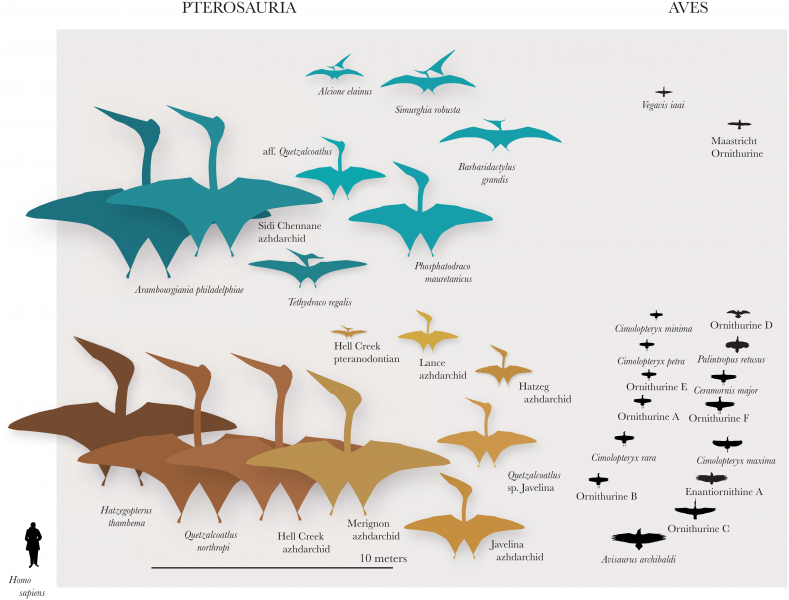

At the end of the Mesozoic Era, only one group of pterosaurs has been recognized, the Azhdarchidae, of which Quetzalcoatlus was a member. This is surprising, considering that pterosaurs are a diverse group of over 200 known species that dominated the skies for over 150 million years. The lack of other pterosaur groups found during the end of the Mesozoic has led to speculation that pterosaurs were on the decline before their extinction, possibly due to competition with ascendant birds.

New research led by Nicholas Longrich (University of Bath), David Martill (University of Portsmouth), and myself (research associate at Vertebrate Paleontology Laboratory, Jackson School of Geosciences Museum of Earth History) turns this question on its head by reporting seven species of pterosaurs from the last million years of their reign, almost doubling the number of species known from the time.

The new study reports a diverse assemblage of marine pterosaurs from the end Mesozoic phosphates of Morocco. Previously, the latest pterosaurs were almost exclusively found in terrestrial paleoenvironments; it was not known that so many ocean-going pterosaurs were alive at the time. Four of these pterosaurs are new to science and were given new species names. Three are similar to previously known pterosaurs and were not given new names

What is not surprising is the identity of the new pterosaurs. They represent previously known groups of pterosaurs that lived millions of years earlier. The new species Tethydraco regalis is a relative of the well-known crested Pteranodon. Whereas, Alcione elainus, Barbaridactylus grandis, and Simurghia robusta are small, medium, and large relatives of the even more bizarrely crested Nyctosaurus. The three unnamed pterosaurs appear to be marine relatives of previously known azhdarchid species, including a giant pterosaur and a smaller version of our own Quetzalcoatlus.

The study also includes an analysis of pterosaur evolutionary relationships, which discovered that some species previously identified as azhdarchids were actually late surviving members of other groups. The possibly fruit-eating tapejarid pterosaurs, the sea-striding thalassodromines, and a couple many-toothed groups make it to the later Mesozoic, and may have been alive at the end. Instead of declining, there is evidence that pterosaur diversity was on the rise at the end of the Mesozoic Era. In addition, we conducted a functional analysis of pterosaur features related to their ecologies and lifestyles, and found that pterosaur functional diversity was also on the rise over their last 20 million years.

Why the 180 on end Mesozoic pterosaur diversity? The initial hypothesis of a decline was based on the reported presence of one pterosaur group at the end of the Mesozoic, the Azhdarchidae. However, it was not until this new study that an evolutionary analysis of all end Mesozoic pterosaur species was conducted and recovered multiple different groups alive at the time. We have known about azhdarchid pterosaurs for almost a half century, and they were the first members discovered of a very large group of pterosaurs. Therefore, many pterosaurs were referred to the Azhdarchidae because there was no other group known at the time in which to classify them.

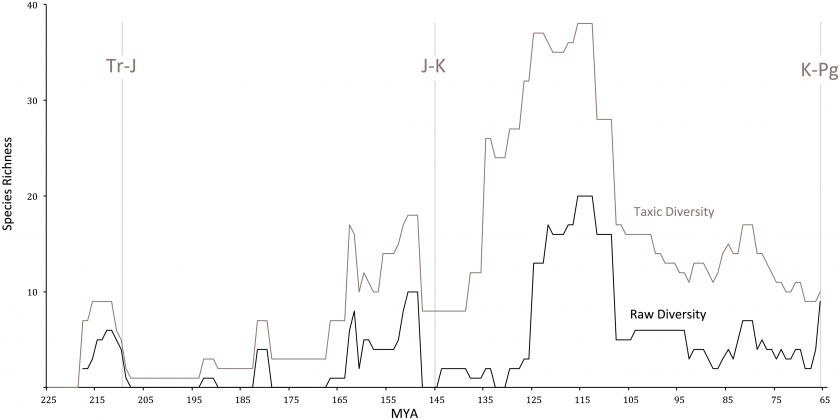

This initial hypothesis has also been tested with diversity curves. Diversity curves should be near and dear to the heart of all geologists because they are what the Geological Time Scale is built upon. The time scale —comprised of the time units memorized in geology classes—is based on what organisms were living when, with the boundaries between them representing their extinctions.

We recognize the Mesozoic Era (literally meaning ‘middle life’) in part because that was when the pterosaurs and dinosaurs were alive. In 2006, the oldest penguin relative was reported from near the Mesozoic–Cenozoic Era boundary, and the authors reasoned that modern birds must have appeared and diversified earlier in the Mesozoic Era to compete with the pterosaurs. They supported this idea with a diversity curve of pterosaur families over time showing an increase in pterosaurs to the middle of the Mesozoic—when the ancestral birds appeared— followed by a steady decrease towards the end of the Mesozoic. The diversity curve of pterosaurs has been repeated multiple times since then, culminating in our analysis of pterosaurs species over time.

These new curves show a different pattern: There are spikes in pterosaur diversity when both ancestral birds and modern birds are thought to appear. There is an extinction event later in the Mesozoic (middle Cretaceous Period), but many pterosaur groups survive and are replaced by diversifications of the pteranodontids, nyctosaurids, and azhdarchids found in the Moroccan phosphates. According to these results, Pterosaur diversity was relatively constant for their last 40 million years and even increased at the end.

Part of the reason that pterosaurs were thought to be on the decline may be the height of the spike in pterosaur diversity in the Early Cretaceous Period of the Mesozoic, which may be artifactually large. Almost all of the exceptional pterosaur deposits, those that record large numbers of species and soft tissue preservation, are from the Early Cretaceous. They are also rather new to science—the Chinese deposits that have produced 55 new species of pterosaurs have done so for only 20 years—and there is a tendency for a large number of species to be named when a fossil deposit is discovered, only to be subsumed into a smaller number of species as we gain a better understanding on their anatomy and variation.

If we can avoid looking at the Early Cretaceous pterosaur spike for a second, the end Mesozoic diversity is roughly that of the middle Mesozoic diversity (Late Jurassic), thought the be the second best time to be a pterosaur.

Finally, the idea that pterosaur diversity was on the decline may most likely another example of the infamous Signor-Lipps effect, a phenomenon based on the apparent decline of organisms towards the end Mesozoic and other major extinction events.

The effect works like this: The fossil record, like all natural scientific records, is incomplete (it would be impossible for it not to be so), and it is highly unlikely that you will ever find the oldest individual or youngest individual of a group. The youngest specimen found could have lived one, two, three, or more million years before the group actually disappeared. This causes a problem to arise when you come to a mass extinction event. These events are very rapid with very few organisms preserved during them, and so most of the groups that go extinct in them have their youngest specimen found one, two, three, or more million years beforehand. And if you are counting species or groups over time as you would to measure diversity, it looks like organisms are apparently decreasing in number towards an extinction event when the effect is artificial. The problem is exacerbated in groups that have poor fossil records, such as the large hollow-boned pterosaurs.

Fortunately, one diverse fauna found at the end of their reign can turn the whole thing on its head.

What about the birds? There is growing evidence that pterosaurs and birds did not directly compete. Pterosaurs are large flying animals and always were, while birds from their beginnings were smaller, with both groups were doing well at the end of the Mesozoic. Rather than being outcompeted by birds, pterosaurs may have provided a barrier to birds becoming larger such that once that barrier was removed, birds could evolve into penguins and all manner of divers forms a few million years after the end Mesozoic extinction. That extinction preferentially killed off the largest species in their groups, and so birds may inadvertently owe their survival to the pterosaurs.

In the end, when you look at the giant wing of Quetzalcoatlus mounted in the Jackson School of Geosciences, know that it ruled the skies at the end Mesozoic Era but it did not rule alone.