Gulf Basin Data: Current Events Spark New Life For Decades-Old Research

October 14, 2016

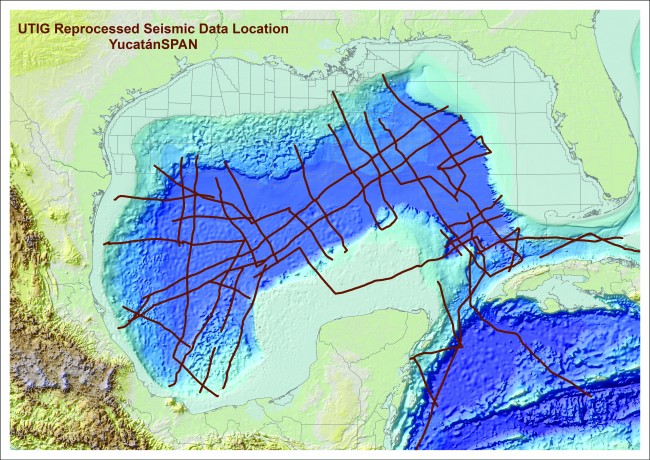

In 1972 The University of Texas Institute for Geophysics (UTIG) began acquiring and processing seismic data in the Gulf of Mexico to better understand its geology. The surveys were the definition of basic research, with scientific cruises crisscrossing between U.S., Mexican and Cuban waters throughout the ’70s and early ’80s simply to learn about the tectonic history of the Gulf of Mexico.

The data wasn’t of much use to oil and gas companies at the time—they weren’t yet drilling into the deep water of the gulf’s basin that the surveys covered. The seismic surveys continued until winter 1982, when the Mexican government, bolstered by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, stopped allowing foreign research exploration on its side

of the gulf.

But after 40 years, the vintage dataset has taken on value besides the academic. After being reprocessed and sold by the seismic services company ION Geophysical, the data has brought more than $4.77 million in royalty payments to The University of Texas at Austin where it has been reinvested into UTIG research grants and used to create the Richard T. Buffler Post-Doctoral Fellowship, a position that supports research in basin-scale depositional systems, such as the Gulf of Mexico.

“Scientists and staff members at UTIG will see the benefits of this partnership every year moving forward,” said UTIG Director Terry Quinn. “It’s truly a win-win scenario.”

The amazing returns on the data come from serendipitous timing. Towards the end of the reprocessing and interpretation, in summer 2014, Mexico announced that it would be lifting a 77-year ban against foreign gas exploration and drilling on its side of the gulf. The reprocessed UTIG dataset— dubbed YucatanSPAN by ION—was the only commercial dataset to include data from Mexican waters.

“If you wanted data immediately when those waters opened, ION was there with YucatanSPAN,” said Andrew Hartwig, a geophysicist at ION who earned his B.S. from the Jackson School in 2009 and began the reprocessing effort as a master’s project at the University of Houston in 2011.

The story of the dataset shows that it’s not enough to rely on new data—old data can be key to driving new discoveries. But to be applied, it needs to be remembered, not stored out of sight and ignored.

Professor Emeritus William Galloway said uniting data, old and new, from onshore and offshore sources was what he and Richard Buffler, a retired UTIG researcher, had in mind when they formed UTIG’s Gulf Basin Depositional Synthesis (GBDS) program in 1995. The program keeps and builds on old gulf data by collecting information from researchers and industry partners in the oil and gas industry.

“The more you know about what is landward, where the sediment came from, the better you can understand, or make predictions about what’s out in the frontier, the basin,” Galloway said. “All the pieces come together if you do good work and create periodic reports and updated maps that are useful.”

Researchers and graduate students involved in the project use data from the GBDS to reveal the depositional history and processes that shaped the gulf, while industry partners, which include national and international companies, apply the data to finding oil and gas deposits. With UTIG integrating decades of data into interactive maps, industry partners are able to skip digging through records and look at results, Galloway said, describing the pitch the GBDS team gave to prospective industry partners when first seeking funding for the research.

The GBDS program has been more successful than anyone ever imagined— transforming from what was planned to be a three-year project to a program in its 21st year, and having its supporting partners grow from 15 to 32.

GBDS Program Director John Snedden said the project’s focus on basic science is the reason for its success.

“We do fundamental science. That’s our first objective,” said Snedden, who is also a UTIG senior research scientist. “And what you find is that companies generally tell you that the best decision making is based on good science, so you have to do the science first.”

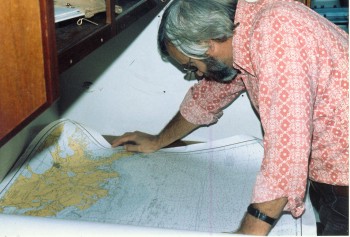

The program also benefits students, who receive training on industry tools as they work on GBDS projects, said GBDS Program Manager Patricia Ganey-Curry. She’s been a part of UTIG since 1978 and even longer if you count her time driving the institute’s research vessel around the gulf while studying at the Texas A&M Maritime Academy.

“Meeting everyone on board and the excitement of being out at sea brought me here,” said Ganey-Curry, who joined the institute right after graduating college.

For over 35 years, Ganey-Curry’s job at UTIG has involved maintaining digital data and acquisition records. It’s a duty that involves overseeing students who input new information and format old data so it is accessible and not forgotten on reels of microfilm or the pages of old binders.

In 2007, one of the student workers was Hartwig, then a second-year geophysics undergraduate.

“As an undergrad I didn’t know how long or how detailed the project was. I was just doing very basic intern, part-time work,” Hartwig said. “It wasn’t until after I graduated and started at ION Geophysical that I started seeing this GBDS dataset, this regional Gulf of Mexico data, being used in the industry, and then it all kind of clicked one day—I was working on this project that oil companies and service companies like ION are really utilizing for frontier exploration.”

He decided to reprocess the UTIG data taken in Mexican waters for a master’s thesis project at the University of Houston, where he enrolled in 2011 while working at ION. The data wasn’t being directly used by clients, but Hartwig sensed that it had potential, despite skepticism from others.

“People have been waiting for Mexico to open up for 20 years, it’s never going to open up,” a co-worker told him. “Well, maybe it will,” Hartwig replied, “maybe it will someday and this will give us an advantage.”

He then contacted Ganey-Curry and got to work.

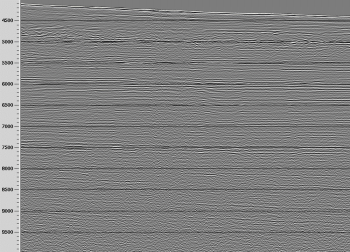

Hartwig was granted permission to reprocess GT3 54 and 55, two sets of data that make a single seismic line taken in 1979 that stretches more than 600 miles from one side of the gulf to the other. Running nearly 40-year-old seismic data through state-of-the-art processing technology improved the resolution immensely, Hartwig said.

The reprocessed data revealed new deposition layers from five million years ago in the Miocene era all the way back to the basement structures that formed the very bottom of the gulf over 100 million years ago in the Jurassic.

Ganey-Curry’s familiarity with the original seismic data helped answer analysis questions that were outside the ability of new technology. For example, she identified an odd reading in the seismic data as an artifact made by swapping out the tapes on which the original data was recorded.

“By no means was it a one man show,” Hartwig said. “I was just building on the work of others at the GBDS and my mentors around the office.”

Hartwig’s thesis work was proof of concept. But rumblings about Mexico finally opening its border led ION to take an interest in reprocessing UTIG’s entire seismic dataset. After negotiating a royalty fee, The University of Texas at Austin agreed.

The announcement that Mexico would be opening for outside exploration came months later, and YucatanSPAN was sold to companies around the world eager to see what could be waiting in an offshore area that had been closed before deep-sea drilling had matured.

“It felt really good, personally, to be a part of something that had a lot of value once those Mexican waters opened up,” Hartwig said.

The millions brought to the university made the dataset the second-highest-grossing royalty from 2014-2015, while the opening of Mexico has gained the program new industry partners and continued to keep students who contribute to the program in high demand, said Ganey-Curry.

“The last five undergraduates in the program are each where they want to be. Four in graduate school, one in industry,” she said.

Rosie Fryer is one of those undergraduates. She earned her bachelor’s in spring 2016, has a summer internship at Hilcorp Energy Company and starts graduate school at the Colorado School of Mines in the fall.

“A lot of people who were interviewing me last year were interested in how I was an active student in research, especially in a sedimentology/stratigraphy focused group with Dr. John Snedden and Dr. Galloway—those are two huge names in petroleum geoscience,” Fryer said. “So it was a great connection for me. A lot of people could easily recognize I was a part of something that was big.”

Though large oil and gas companies are now starting to take their own seismic readings in Mexican waters, the data from the 1970s campaign may have more to give.

According to Ganey-Curry, UTIG has given ION permission to reprocess the entirety of its Caribbean data, which includes readings taken off the coast of Cuba.

“We have the same type contract where if they sell the data we get a royalty after the derivatives of the sales,” she said. Like Mexico, Cuba has been off limits to private drilling for decades. But with travel restrictions loosening and American leaders, including President Obama and Texas Gov. Greg Abbott, visiting, there’s talk that its waters, too, may soon be opening up.

The dataset’s renewed value shows that UTIG’s mission to learn about the history of the Earth can have unexpected benefits. That’s because geological data has long-lasting usefulness, Galloway said.

“In most sciences it’s really fair to say that, other than historical reasons, you don’t need to read the literature that’s more than 10 years old because the new stuff replaces it. But geology, in that sense, is different,” Galloway said. “As long as data was collected by a good observer and preserved, it can be just as valuable now, and even more valuable than it was when it was collected, and that seismic data is an example. The raw data may have been cycled and used as acquired, done some useful things … but you can come back to it and learn whole new things.”

Back to the Newsletter