Texas Fossil Helps Clarify Alligator Family Tree

January 15, 2021

Families are complicated. For members of the Alligatoridae family, which includes living caimans and alligators – this is especially true. They are closely related, but because of their similarity, correctly identifying them can even stump paleontologists.

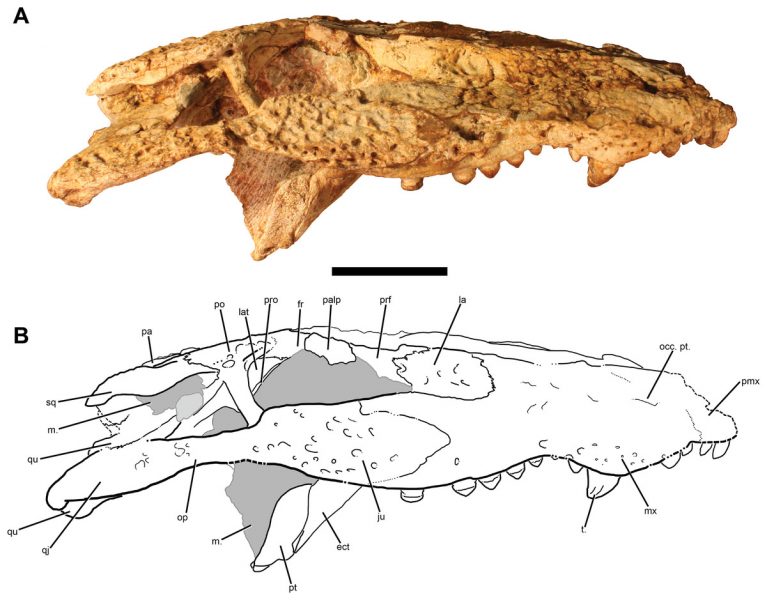

But after the recent discovery of a partial skull, the caimans of years past may provide some clarity into the complex, and incomplete, history of its relatives and their movements across time and space.

The fossil is 42 milllion years old, from southwest Texas, and may have belonged to one of the last prehistoric caimans to roam the United States. It will be housed at the Texas Vertebrate Paleontology Collections at the University of Texas at Austin’s Jackson School of Geosciences, where it will be preserved and maintained in perpetuity.

“Any fossil that we find has unique information that it contributes to understanding the history of life,” said Michelle Stocker, an assistant professor of vertebrate paleontology at Virginia Tech and a research associate at the Jackson School who led the research. “From what we have, we are able to understand a little bit more about the evolutionary history of caimans and the alligatorid group, which includes alligators and caimans.”

Their findings were published in PeerJ, an open access peer-reviewed scientific journal.

The research was co-authored by Chris Kirk, a professor at The University of Texas at Austin’s Department of Anthropology and a Jackson School research associate, and Christopher Brochu, a professor at the University of Iowa.

The fossil was discovered in 2010 at Midwestern State University’s Dalquest Desert Research Site, which is in the Big Bend region of Texas and includes extensive exposures of the Devil’s Graveyard Formation. The formation preserves fossils from the latter portion of the Eocene epoch, a period of time covering 15 million years of prehistory.

In 2011, Stocker and the team returned to the site to collect a key bone that remained in a hard sandstone block.

What they discovered was a partial skull. At the time, paleontologists were convinced that the skull came from a specimen that was a closer relative to alligators than caimans.

The skull’s braincase was key to identifying the fossil. Since no two species have the same braincase, finding one can provide much needed information.

After further investigation into this fossil’s braincase, Stocker and the team were able to determine that this was most likely a caiman.

The caiman was deemed to be 42 million years old using a combination of investigative techniques, including radiometric dating, biochronology, and biostratigraphy, where paleontologists use the relative order of the fossilized animals to find out how old the rocks are.

With the age of the fossil and its location in mind, paleontologists are able to add to an ever-growing story about a large range contraction, or a climate-related localized extinction, that occurred millions of years ago.

“This caiman seems out of place,” said Brochu. “Caimans today are a South American radiation, and data from modern forms, including DNA, would suggest a very simple single origin from a North American ancestor. This new form, along with some older North American fossil caimans, suggests a far more complex early history with multiple crossings of the seaway that separated North and South America until fairly recently.”

There is even more to know about caiman history. But since the specimen is far from a complete skeleton, paleontologists still have some knowledge gaps to fill.

“If we can find another individual, we will get a better sense of its relationships, and it might be able to say something about what variation could be present in this taxon, or how they grow, or where else they might be found,” said Stocker. “This is a one and done kind of fossil right now. Hopefully there are more out there.”

This release is an edited and abridged version of a release from Virginia Tech.

Read the original at: https://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2021-01/vt-nfp011421.php