The Science Didn’t Stop: JSG’s Christopher Bell Shares Hidden History of Natural Scientists in the Service During WWII

March 9, 2020

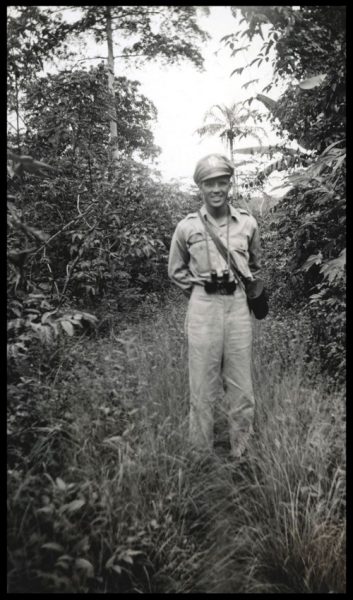

During World War II, American scientists were part of the millions of men who enlisted or were drafted into the United States military. Among them were natural scientists – ornithologists, mammologists, herpetologists and others – who turned war zones into their own independent research sites.

They collected tens of thousands of scientific specimens from across Europe, Africa and the Pacific region, wrote research papers about war zone fauna, and corresponded with museums back home, which gladly received their finds.

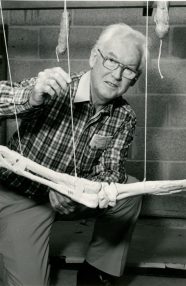

Today, these documents and materials are spread across the country. They’re stored in museum warehouses, on the shelves in museum archives, and kept by families. For about the past decade, Jackson School Associate Dean Christopher Bell has been working on finding them, and talking to individuals who actually lived it.

On February 13, 2020, during a DeFord Lecture presentation, Bell shared a sample of the history that he has uncovered so far.

“Where I’m going to take you today are the kinds of things I’m investigating, the kinds of things I’m chasing,” Bell said. “This is not a finished story.”

Before presenting the facts of his research, Bell set the mood. A 1940s soundtrack softly played as the audience entered into the Boyd auditorium where the talk was held. And after a brief introduction, Bell cut the lights to tell the story of U.S. paratroopers’ nighttime D-Day jump, complete with a couple of audience members flashing refurbished colored lights that were actually used by the military to mark supplies during night time jumps.

The scene-setting isn’t just showmanship. Bell said that interacting with artifacts from the era, whether its music or military supplies, helps illuminate the context in which the scientists lived and worked. Bell said that he titled his talk “Chasing Elusive Propinquity” to emphasize that aspect of the research, with “propinquity” meaning a proximity in space and time. Fittingly, according to GoogleBooks, the word peaked in usage during the decade leading up to WWII.

Bell grew up around WWII veterans, so he has been learning about the history of the war in some way since childhood. But he said it was a handful of discoveries that set him on his current research path.

Through a conversation with his wife’s great aunt, Mary Shelburn, he learned about the Bug House, a lab and museum in Eastern North Carolina that was run by teenagers during the pre-war years, and whose membership enlisted after the United States entered the war following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941.

Bell found WWII era papers published by the former Smithsonian curator David H. Johnson on rats introduced to the Solomon Islands, that listed the U.S. Naval reserves as Johnson’s affiliation.

And while researching the Bug House at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Science, an archivist told Bell about a collection of letters between WWII service members and the museum’s then director. A letter in that archive even led Bell to rediscover specimens of a bird-of-paradise, a tropical plumed bird, that was sent to the museum by a service member.

Together, the experiences raised the question that launched the research project. As Bell put it:

“How common was that, for people that I know as mammologists, or herpetologists or ornithologists, how common was it for these people to be in uniform and continue to do what they do?”

From what he’s uncovered so far, the answer is quite common. Even when at war, the science didn’t stop.

During the presentation, Bell shared short vignettes of scientists in the service.

For example, Robert Hinde, a major general in the British army, was said to have interrupted a briefing for an impending battle by calling out for a matchbox in which to capture a passing caterpillar. Hinde’s quoted as saying:

“You can fight a battle every day of your life, but you might not see a caterpillar like that in 15 years!”

And there was Albert Mead, a snail researcher and parasitologist who called himself the “Travelling Snailsman.” His expertise was in high demand for the war effort. According to Bell, every United States, British and German division had a dedicated parasitologist and entomologist whose job was to keep service members safe from parasites and bug-borne pathogens. Mead spent his time doing just that for United States troops, first serving in the Pacific and later in Africa.

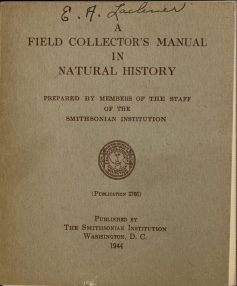

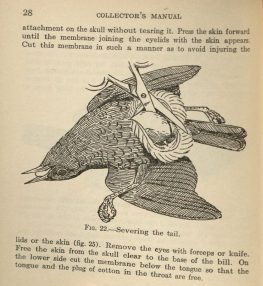

Bell also shared how museums, in particular the Smithsonian Institution, helped foster the collection of scientific specimens by sending out how-to guides for collecting and preserving specimens – from how to skin and stuff a bird, to how to excavate a fossil.

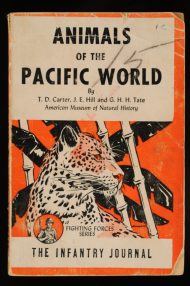

The Smithsonian also directly contributed to the war effort by publishing guides to geography and wildlife in war zones, and conducting research, including starting a journal called War Background Studies. An example of one of these studies is the migration patterns of snapping shrimp, which form large schools that can interfere with radar systems.

The U.S. armed forces also released their own paperback books for service members, including those about wildlife and nature in war zones.

Along with books and research, Bell also pointed out how zoology intersected with war in some unusual ways. “Bat bombs” – which are exactly what they sound like – were tested by the U.S. military but never actually deployed. And a bear named “Corporal Wojtek” became, on paper at least, an actual corporal in the Polish army as a means to skirt the military’s ban on animal mascots.

When the war ended in 1945, some scientist service members returned to their studies and research. That included the former director of the Jackson School’s vertebrate paleontology collections, Wann Langston, who enrolled in graduate school after serving in the U.S. Navy. In the case of Howard Lowe, an alumnus of The University of Texas at Austin and a former member of the Jackson School’s Advisory Council, a fascination with volcanoes that he saw while deployed to the Pacific inspired him to change his major from engineering to geology when he picked up his undergraduate studies after the war.

However, war took its toll. The death of 15 million in the military and 45 million civilians, globally, ruptured communities across the world, including the scientific community.

“All the things that these people could have contributed to society were lost with them,” Bell said.

The destruction of museums, libraries and scientific collections dealt another blow.

By chasing elusive propinquity, Bell is doing his part to document history and preserve artifacts from the era that relate to natural science, the scientists and the lives they lived. As he closed his talk, he encouraged the audience to stop by the third floor of the Jackson Geological Building to see a display case for WWII artifacts – including books, papers, military gear and photos – that he’s found throughout the course of his research.

As for future research on science while at war, he plans to keep up the chase.