Geosciences at the Gran Museo del Mundo Maya

May 10, 2016

The Gran Museo del Mundo Maya is a museum dedicated to the history of the Maya people, a population that includes an ancient empire as well as people that inhabit the Yucatán today.

While other museums I’ve visited usually stick to anthropology when exploring cultures, the Museo del Mundo Maya emphasized the importance of geology and natural history in shaping the land where the Maya live. That made it the perfect place to start my weeklong excursion into Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula to report on an amazing geosciences project headed by the UT Jackson School’s Institute for Geophysics – the drilling of the Chicxulub crater, which was formed by the asteroid that wiped out all non-avian dinosaurs 66 million years ago.

Some exhibits included:

An array of soils found in the Yucatán, complete with the Maya word for each type.

Examples of the seashells from the region, which over millions of years were crushed together to help form the carbonate rock that makes up most of the Yucatán rock today.

A model of interesting water features that can be found underground. The exhibit described Yucatan limestone as acting like a “stone sponge” that retains water. As the water erodes the rock away, complex networks form beneath the ground, including cenotes–a type of water-filled cave that the ancient Maya people saw as a portal to the underworld.

According to the museum, the bottoms of some cenotes are coated in a blue pigment, remnants of paint that covered victims of human sacrifice that were flung into the cenotes as offerings to gods.

But the highlight of the natural history portion of the Museo del Mundo Maya were the exhibits on the Chicxulub impact–a history-altering event that occurred when a six-mile-wide asteroid slammed into the planet 66 million years ago, killing an estimated 75 percent of species living during that time, including all non-avian dinosaurs.

A film, called “Armageddon” gave guests an idea of what the impact looked like: Fire falling from the skies, the oceans riddled with dead fish, leaves dried by acid rain.

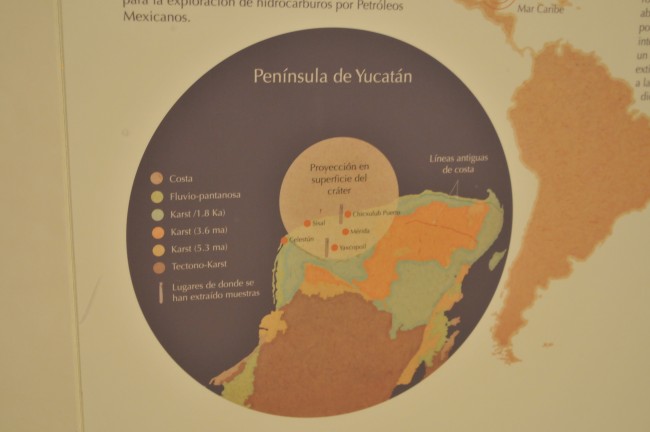

It was followed by exhibits that explained how the crater was preserved for millions of years under the Gulf of Mexico and how scientists found it. The tectonic stability of the region ensured that the crater wasn’t disturbed or distorted, while geophysical imaging of the gulf by the Mexican oil company PEMEX revealed the presence of the crater in 1978.

The Chicxulub exhibit also included core samples taken from the crater.

It was interesting to see the cores because it gave me an idea of what I hope to see tomorrow when I board the L/B Myrtle, the ship where Jackson School scientists and others from around the world are coring samples of the crater. While other expeditions have cored into the crater’s edges, the researchers are coring into the crater’s peak ring, a feature that forms in all asteroid impacts, yet remains mysterious. Peak rings have been observed on the moon and other rocky planetary bodies, but all known above-sea examples on Earth have been eroded away. Chicxulub’s ring remains because it was preserved under a layer of sediments beneath the sea.

No one knows how the peaks formed, or what sort of influence they have on the environment–they may have shot debris into the atmosphere during their formation, or served as a habitat for extremophiles that thrived in the crater after the impact. The newly retrieved core samples can help answer these questions. We just have to wait and see what they have to say.