Volcano Forensics

November 2, 2015

By Monica Kortsha

Millions of visitors flock to Yellowstone National Park each year to see its steaming geysers, iridescent pools and carved, rugged landscape. For the last five years, Jim Gardner, Kenny Befus and a team of undergraduate students from the Jackson School of Geosciences have been among them.

Instead of rushing to Old Faithful on their visits, Gardner, a geology professor and volcanologist, and Befus, then a Ph.D. student at the Jackson School and now a geology professor at Baylor University, would lead the team deep into Yellowstone’s backcountry to the remains of ancient lava flows that dominate the park’s landscape.

The backcountry lava flows, as well as the tourist-traversed pools and geysers are all signs of a “super volcano” laying in wait beneath the park. Over the past 2.1 million years it has explosively erupted as least three times, spewing more ash, pumice and smoke than any eruption in recorded history, and creating a caldera that takes up one-third of the park’s total area. However, the last time a “super eruption” happened Homo sapiens hadn’t even evolved yet.

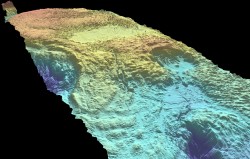

Much more frequently Yellowstone’s magma has been exuded in the form of passive, massive lava flows. Since the last violent eruption, about 30 of these flows — which can reach up to 12 miles wide and hundreds of feet deep — have oozed across the land, with the most recent occurring about 79,000 years ago.

It’s the traces left by these flows that have brought Gardner and Befus to Yellowstone over the years. By examining the lava, they’re working to understand what volcanic conditions caused Yellowstone’s magma to steadily effuse, rather than explode, and to add insight into the eruption type that dominates Yellowstone’s past and could happen again in the future.

“Our main target was understanding how these things erupt, but don’t go boom,” Befus said.

AN INTEREST ERUPTS

Gardner grew up near Dallas, safely outside of the range of any volcanoes — save for that aforementioned super eruption. But he took an undergraduate geology class at Southern Methodist University, and he’s been studying volcanoes ever since.

“I just basically became homed in on the actual physical nature of the eruption and understanding the processes that occur,” Gardner said.

He’s studied the ash and pumice that entombed the city of Pompeii, and helped reveal how the pyroclastic flow created by the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens came to a stop as it swept down from the peak. Prior to joining the Jackson School in 2003, Gardner worked at The University of Alaska Fairbanks and was on staff at the Alaska Volcano Observatory where he evaluated hazards and the eruptive history of volcanoes across the state. And now, as a volcanology professor, he leads undergraduate students each year to New Mexico to study the Valles Caldera, the first volcano Gardner himself ever visited.

The sites he has studied, while varied, have one thing in common: the eruptions happened well into the past, from decades to hundreds of millions of years ago. Like a forensic detective, it’s his job to go to the eruption scene, examine its aftermath and reconstruct the environment that made the volcano blow in the first place.

“By providing information and understanding about eruption processes, maybe others can use it to forecast eruptions and mitigate hazards,” Gardner said.

The key clue to glean from the scene is lava — long solidified into various kinds of rocks by the time Gardner arrives.

GO WITH THE FLOW

The Yellowstone volcano produces rhyolite lava, a silica rich form that solidifies into different types of igneous rock depending on its eruption and cooling conditions. During explosive eruptions, magma is shot into the air, where it instantly solidifies and falls as ash and porous pumice. But during passive eruptions, it quickly cools into other varieties of rhyolite rock that make up the lava flows today.

Obsidian is perhaps the most distinctive rock produced by rhyolite lavas. Pure black, smooth and glassy, its appearance is the result of having cooled so quickly that the silica it’s made of didn’t have time to arrange into a crystal lattice structure.

Native American tribes in the Yellowstone region valued obsidian outcroppings as a raw material for spear tips, arrowheads and cutting tools — the smoothness made for easy shaping and sharp edges.

Gardner and Befus value its smoothness, too, but for different reasons. It provides an unobstructed view of minerals and gasses that were trapped in the lava during the eruption. These microscopic traces are the best clues to what the eruption environment was like, Gardner said.

“These are the quenched products of the magma chamber as it was erupting,” Gardner said. “We look at these products to try and reconstruct what was occurring in the magma chamber before the eruption, as well as the dynamics of the system during the actual eruption.”

So while other visitors would leave Yellowstone with keychains and mugs, Gardner, Befus and the student researchers would return to the Jackson School with fist-sized samples of shining, black obsidian hammered off nearly a dozen lava flows from across the park.

UNDER THE MICROSCOPE

Tim Prather, then an undergraduate, chips stone samples from a lava flow in Yellowstone. He is now a graduate student at the Jackson School.

Volcanic rocks are like tape recorders of the chaotic environment inside a volcano’s magma chamber, Gardner said. The minerals and gasses held in them provide a record of variables, such as pressure, temperature and gas concentration, which influence the eruption process.

Gardner references the old-technology of a tape recorder for a reason; a volcanic rock captures its environment by constantly recording traces of new conditions over those left by older ones, like a cassette tape used over and over again. The result is a record that is a collage-like conglomeration of the volcanic environment.

“When we’re looking at the products at the surface, we’ve got the entire record of it, but it’s written over each other,” Gardner said.

Reading the record is a matter of close analysis. Trace element concentrations, such as iron and magnesium, reveal pressure ranges; microscopic bubbles trap samples of gas from throughout the eruption that can be identified using

spectroscopy; and microlite crystals, which rotate and align together in the flowing magma, can give clues on how quickly magma was flowing through the crust toward the surface.

Clues like these gleaned from a close analysis of volcanic rock allow Gardner to reconstruct a timeline of events for a volcanic eruption. And an experimental petrology laboratory lets him to test it by turning volcanic rocks back into magma.

In his simulated magma chamber, Gardner can adjust variables, such as heat, pressure, and gasses present, to model different eruption phases and conditions. However, unlike a real volcano, Gardner can stop the eruption at any point by quenching the magma back into solid rock.

“My tape recorder is not fixed. It’s not overwriting itself,” Gardner said.

By comparing the final quenched magma to an original sample, the researchers can see if their simulated environment created outcomes comparable to an actual eruption.

“It’s a simple matching game really,” Befus said. “But it’s one of the major techniques we use.”

YELLOWSTONE FUTURE AND PAST

The obsidian samples from Yellowstone all hold clues about the particulars of the eruptions that forged them.

Through analysis and the petrology lab, Befus reconstructed the eruption that formed Douglas Knob, a lava dome made by the slow effusion of magma, for a portion of his Ph.D. dissertation.

According to Befus, it went something like this:

On a day roughly 120,000 years ago, rhyolitic magma stored about a mile under the ground at 1,400 degrees Fahrenheit began to rise at a rate of about half a millimeter to 1.3 millimeters per second. Twenty to 70 days later the magma reached the surface and began pouring out of a 1,600-foot-long fissure in the earth. This lasted for anywhere from 17 to 210 days, building a mound of lava in the process.

The shallow depth and slow rise of the magma in the eruption 120,000 years ago bodes well for responding to any future passive eruptions, Befus said. The movement of the magma would likely break rock as it made its way to the surface, creating little earthquakes that would signal Yellowstone’s slow stirring. It’s also possible that the amount of magma in a pre-eruptive magma chamber could be seismically imaged using techniques similar to those used by the oil and gas industry to search for energy reservoirs.

“All of these signals mean that people are going to have time to collect the data that indicate that effusive process is going on,” Befus said. “There should be warning.”

It is comforting knowing that Yellowstone’s future eruptions will likely be slow, controlled and well-announced, but a super eruption is still within the realm of possibility. And as of now, it’s still an open question on what exactly triggers magma to degas slowly and erupt passively or to let its gas out all at once in a violent eruption.

“We know that one has to go fast and the other has to go slow, but the reason why one is going so fast is something we don’t know,” Befus said. “That’s where I plan to spend my next few years. This idea of an eruption trigger, I’m excited about that.”

But even as knowledge about volcanoes and eruptions evolves, Gardner said it’s a field of science where chance will be in control.

“We don’t predict volcanoes. They’re too chaotic in nature,” he said.

Instead, the reconstructions offer a peek into a future that could be because it has been. For Yellowstone they indicate a future where eruptions would overwhelmingly be lava flows that move so slow they would likely be the latest geothermal attraction at the park, not a danger. Of course, you can’t rule out a violent eruption.

But Befus, for one, isn’t losing sleep about that.

“The most recent eruptions have not been the famous super eruptions that get press on the news and on the Discovery Channel, but instead it’s been these massive lavas,” he said. “So people who are cataclysmic types, calm down a little bit. It’s most likely not going to do that.”

Back to the Newsletter