The Man Behind the School

November 2, 2015

by Anton Caputo

When Jack Jackson decided to leave his fortune to The University of Texas at Austin, it forever changed the face of geosciences at the university, the state and beyond.

The university already had a long and storied history in geology and the geosciences dating back more than a century. The Department of Geology was formed in 1888 and the Bureau of Economic Geology in 1909. The Institute for Geophysics, by far the baby of the group, dates back to 1972.

The Jackson estate gave the university the ability to tie the units together, first as a school in 2001, and later as a college in September 2005. What resulted was the formation of one of the largest and most prestigious schools of geosciences in the world.

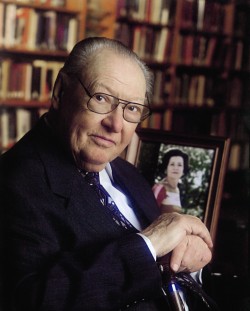

Jack’s choice to leave his estate to the university was a gesture to an institution he loved and credited with playing a large role in his success. He and wife Katherine, or Katie, for whom the school is also named, never had children. In a way they adopted the university, said Bill Fisher, first dean of the Jackson School of Geosciences.

“The university became their children,” Fisher said. “Jack loved this place. He had fond memories of geology here.”

Beyond loving the university, those close to Jack said he was devoted to the state and people of Texas and held a bedrock belief that education and the understanding of the Earth were paramount to ensuring they thrived in the future. His Feb. 27, 2002, letter making his plans official underscored that belief:

“The resources of the Earth have been very important to me and to what Katie and I have been able to achieve. The continued study and understanding of geology and the resources and environment of the Earth will be important to The University and the citizens of Texas in the future. Our intent to commit the residue of the estate is in that spirit.”

Despite the generosity of Jack’s actions and the size of the estate — it was conservatively estimated to be worth $150 to $200 million in 2002 and is now valued at greater than $300 million — he did not view it as a gift.

“He made that very clear,” said Scott Tinker, director of the Bureau of Economic Geology. “Jack said, ‘I’m not giving you this money. We’re investing in The University of Texas.’ ”

Fisher, as director of the Geology Foundation, worked closely with Jack for almost 20 years. He and Tinker were among a group of five university administrators that Jack became close to in the later years of his life. The others — then president Larry Faulkner, former president Peter Flawn, and then dean of the College of Natural Sciences Mary Ann Rankin — rounded out what Jack would sometimes refer to as his university family.

“Honestly, it’s hard to convey what an interesting and funny and truly lovely man he was,” said Rankin, who is now Provost of the University of Maryland. “I still miss him.”

Humble Beginnings

The Jack those at the university came to know in his later years was a very wealthy man thanks to his success in the gas fields of Wise County and astute real estate investments in the Dallas area. He was every bit the independent oilman — shrewd, hardworking and affable, yet tough when he needed to be. He was a great storyteller by all accounts. But he was unlike the Hollywood portrayals of oilmen from the era.

Absent were the oversized cowboy hats or big cigars. He did not live large or ostentatiously — although in later years he did like to play golf with his friend Byron Nelson and other celebrities during fundraising events for charities that Jack supported.

He lived well, in a nicely kept ranch-style home in North Dallas that his friends describe as solidly upper-middle class or the type of home you might expect a college professor to live in. He drove Cadillacs — but he kept them for a decade or more. He liked to eat out, but his standby meal was chili from Jason’s Deli. When he occasionally went more upscale, it was often the Olive Garden.

He had a lifelong love affair with his wife Katie. In fact, Jack left geology and the oil business flat in 1960 when Katie, who was tired of his long absences in the oil fields, reportedly said she would have been better off marrying a shoe salesman. He would later tell his friends that he never spent another day apart from Katie until her death in 2001.

Katie seems to be the one instance where Jack would abandon his Depression Era spending sensibilities. Rankin remembers several times in Jack’s later years when he would become sentimental talking about Katie, and would show Rankin the closet full of couture gowns he bought for Katie or take her to the bank to look at the jewelry he bought his beloved wife.

“It meant a lot to him that he had bought that for her even though they clearly didn’t spend a lot of money on their home or anything like that,” Rankin remembers.

Katie, in classic Jackson fashion, rarely wore the jewelry, instead choosing to wear duplicates that Jack had made for her.

But like many members of the Greatest Generation who would achieve remarkable success, Jack did not come from wealth.

“Jack started as a regular, poor kid,” said Jim Langham, Jack’s longtime accountant. “He didn’t have any money … Jack was successful because he worked, he was smart, he saw the opportunity and he took advantage of it.”

Born in East Texas in 1913, Jack lost his father to influenza at the age of three. He was raised by his mother, a talented woman who became director of public welfare for the City of Dallas.

Jack grew up working. Selling newspapers, bagging groceries and later working in a cotton gin and a department store, were a few of his endeavors. At one point in high school he even branched out into small business by selling his own brand of pomade while delivering newspapers.

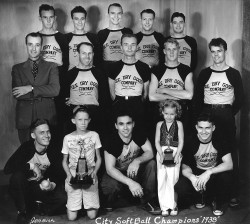

He was an exceptionally good baseball and fast-pitch softball player and a top-notch southpaw pitcher. This skill would prove to be a valuable professional asset when Jack was a young man looking for employment in an era when companies would often field semi-professional teams and engage in national tournaments. His ball-playing prowess was instrumental for obtaining one of his early jobs at Arkansas Fuel.

By the time Jack graduated high school, the Depression gripped the country. Luckily, oil production was booming in East Texas, and an older cousin, John Atkins, agreed to put Jack to work at his gasoline plant. Jack learned the operations from the ground up — digging ditches, working on pipelines, and even spending time in the chemistry lab. His wage was 25 cents an hour.

Jack’s cousin would eventually let him go, letting the young man seethe for a little while under the impression that he had been fired before explaining that Jack had learned all he could at the gas plant and that he was going to help him pursue a higher education.

College and War

Jack chose The University of Texas at Austin to pursue a degree. However, his first foray into academic life during the fall of 1935 didn’t go well. He was determined to pursue his degree, but simply hadn’t yet developed the academic skills necessary to succeed at the university.

On the advice of Assistant Dean of Men Arno “Shorty” Nowotny, Jack transferred to Temple Junior College to improve his academic skills before reentering the university.

“He learned how to study is what it really comes down to,” Langham said. “It’s like a lot of those guys that needed to get into the regimentation that it takes to get a professional degree. That’s what he needed to do and that’s what he did.”

The move to Temple Junior College would prove pivotal in Jack’s life. It was during this time that he would meet Katherine Elizabeth Graeter, his future wife and lifelong partner. It was also one of those life experiences that seemed to color Jack’s view of education.

“Because of his own path, Jack knew that young people are not just programed to succeed,” Faulkner said. “They haven’t necessarily had the right set of experiences at any given moment in life and you need to be open-minded about giving them a chance about getting those experiences together.”

Jack eventually returned to The University of Texas at Austin. He graduated with a geology degree in 1940 and took a job at Arkansas Fuels. World War II broke out soon after and he enlisted in the Navy, but the War Department had other ideas.

The nation, gearing up for a war it was not prepared for, desperately needed aluminum for planes and other equipment. Jack soon found himself assigned to the bauxite district of Arkansas to help find deposits of the precious ore.

Jack would spend the war doing just that. The experience proved invaluable for a geologist starting his career and would play a pivotal role in his later success.

Wise County

When the war ended, Jack went back to work for Arkansas Fuel, but was hired away by independent oilman Jay Simmons and oil investor Arthur Cameron. For six months, Jack’s role with the duo entailed promoting events and entertaining celebrities and potential investors as much as it did geology.

But Simmons eventually sent Jack to Wise County to check on the claims of a rancher — former British Colonel Jimmy Hughes — who was convinced he had oil under his land. Jack saw enough potential in the well logs the rancher shared with him to start an investigation of his own that would eventually lead to the Wise County gas fields.

“Everybody thought Jack went out there and found this oil and gas and he was rich. It didn’t work like that,” Langham said. “It took a long time. It took them seven or eight years to get that thing going.”

Jack spent almost two years pulling together logs, maps and whatever information he could find on the geology of the area. Ultimately, it was his experience gained during the war working the bauxite deposits in Arkansas that brought the geology into focus, as Jack explains in his biography:

“The only difference between a bauxite deposit and a porous conglomerate in the Fort Worth Basin is that the weathering of the former dissolved out the silica and concentrated the alumina content. The weathering of the latter reduced silica and formed holes (porosity) which were ultimately filled with oil or gas rising up from the interbedded gray shales. It was that simple. The trick was to learn the pattern of deposition. Once that was established, the rest was mechanical. And I had learned the sedimentation pattern in the Arkansas bauxite ‘field laboratory’ during the war. Core drilling and seismic maps were used to locate the subsurface ridges and valleys there. The thick bauxite deltaic deposits occurred in and along the valleys where the deltas had built rather than on the crests.

The conglomeratic pattern in the Fort Worth Basin was very similar. So I transferred my bauxite knowledge over to the Fort Worth Basin. Nobody working Wise County had the kind of background that I had, so they didn’t have the geological insights I did. I could look at a map and see 6,000 feet into the ground. The area looked like a room full of sawdust filled with thousands and thousands of cups and saucers and platters and bowls scattered throughout. You did not need a geophysical map which would reflect the valleys and ridges. There was no such map of the entire county, but after months of painstaking detail work I was able to put together numerous seismic maps of small areas like a jigsaw puzzle. All of the sudden the entire area came into focus — the same pattern of ridges and valleys found in the Little Rock bauxite field.”

Hitting it Big

Hitting it Big

Jack’s theories were proven out by test wells drilled in 1950, but he couldn’t get his employers, who were preoccupied with oil plays elsewhere, to pay attention. So Jack quit and set out on his own, working as a geologist in the oil fields to pay his bills while pursuing his own geological work in Wise County’s Fort Worth Basin.

The fascinating series of events that took Jack from scratching out a living in the oil fields to hitting it big in Wise County is detailed in Jackson’s own book “Wise County: 25 Years of Progress” and his 2005 biography commissioned by the Jackson School titled “The Jack Jackson Story-Reflections of a Geologist.”

But it was a 1952 chance meeting with a landman in a Lubbock coffee shop that really got things moving. The landman mentioned Jack’s deal to a friend in Denver, who passed it on to an associate in Tulsa, who then contacted a Chicago bookie known to frequent a well-known casino in Galveston. The bookie mentioned the deal to a card dealer whose son, as fate would have it, worked for Jonny and George Mitchell. George, of course, would later gain fame as the father of hydraulic fracking and the current shale gas and oil boom that has done much to reshape the country’s domestic energy supply.

“I think one of the great stories about the Fort Worth Basin is that Jack’s vision drew George Mitchell in, and George Mitchell’s activity there lead ultimately to the development of horizontal drilling and fracking,” Faulkner said. “Those two guys together, those were tremendous visionaries.”

The fortuitous series of events quickly brought Jack into contact with a group of investors with enough capital to pursue Jack’s plans and enough knowledge to see the sense in them. The group originally offered to put Jack on the payroll as the project’s geologist for $50,000 a year. But Jack declined, saying he didn’t want to be an employee.

After discussing the situation with Bob Smith, who was affiliated with the Mitchells and would become Jack’s close friend and mentor, Jack took a 3-percent “override” in the venture. This allowed Jack to make income off the venture if and when it produced income without having to make a capital investment he couldn’t afford.

During the next several years the group acquired more land and drilled more test wells, with Jack working tirelessly as the exploration geologist. But money from the investment was not forthcoming. The group could not strike a satisfactory deal with Lone Star Gas, which served Dallas and Wise County. They eventually struck a deal with the city of Chicago, but it took a new pipeline, a visit to Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley, a new gas processing plant and the defeat of a federal lawsuit filed by Lone Star to get gas flowing from Wise County.

Finally, in late 1957, it was all finished. Gas was being piped to Chicago, and Jack’s hard work had paid off — handsomely.

Life After the Rigs

Jack continued to work the oil fields hard for a couple years before Katie finally put her foot down about the long hours and time away from home.

Once she did, Jack left the profession quickly. The couple took a two-month vacation to Europe and then settled into life in Dallas, where Katie quickly became a key figure on the social scene.

Jack, on the advice of Bob Smith, invested heavily in real estate in North Dallas. Much of the property would eventually be turned into the North Dallas Tollway, making him another fortune. Jack also worked hard on the political campaign of Dolph Briscoe, becoming something of a kingmaker in Briscoe’s run for governor.

Jack and Katie were strongly religious and believed in the power of education and medicine to help mankind. They donated heavily to Presbyterian Hospital of Dallas, Texas Lutheran College, Austin College, Temple Junior College and many more causes, including, of course, The University of Texas at Austin. Katie was a member of the Texas Lutheran College’s Board of Regents for two decades and an honorary member of the Presbyterian Hospital’s Board of Trustees.

But it was Jack’s election to The University of Texas Geology Foundation Advisory Council in 1975 that would set the scene for

Jack and Katie’s ultimate show of philanthropy. Jack had been out of geology for 15 years when he was elected, but the foundation did so at the urging of Samuel Ellison Jr., who helped create the foundation and was chair of the Department of Geological Sciences.

Ellison had known Jack since the Wise County days and was quick to introduce him to Fisher, who in 1970 became director of the Bureau of Economic Geology, and later the chair of the geology department and the Jackson School’s first dean.

This relationship, which developed over many years, would lead to the Jacksons donating $15 million for a new wing to the geology building and $25 million to form the new school before Jack made the momentous decision to leave the bulk of his estate to The University of Texas.

There wasn’t perfect agreement among Jack’s university family after Jack made his decision known. At the time, the geology department was part of the College of Natural Sciences. Fisher and Flawn, who had discussed pulling the university’s three major geosciences units together years before, saw this as the opportunity to finally accomplish that mission.

“That had always been a goal of mine, but we never had the capability to do it,” Flawn said. “The gift made it possible.”

However, Rankin, who was dean of the College of Natural Sciences at the time, thought the department should stay under the college, arguing that it could continue to strengthen the important ties it had made with the other sciences.

“I felt like geology could grow just as much and be as ascendant nationally and not sever the ties with the college,” Rankin said. “But there were no terrible choices.”

Ultimately, Faulkner, the university president, agreed with Fisher and Flawn that the geosciences should be tied together as a single school and the decision was made.

The Jackson School

Looking back some 10 years after the Jackson School was formed as a college and almost 15 years after it was first formed as a school, those who knew Jack agree that he would generally be pleased with the results. Although they also said he would likely be anxious to see the Jackson School improve its top 8 national ranking to number 1.

“Jack appreciated that the science of geology was changing, but he didn’t want us to abandon the expertise we developed in oil and gas and natural resources,” Flawn said. “He wanted us to include the environment too. But mainly, he wanted us to get better.”

Tinker too has clear memories about Jack’s desires for the school.

“Make sure you work on things that are going to differentiate geosciences and have an impact on the world,” Tinker said.

Beyond straight geology, Jack was very interested in water resources, and those who knew him agree that he would be happy about the Jackson School’s leading work on the issue.

“He would sit and look out his office window and look out at the Trinity River and say, ‘Could you imagine messing up a nice river like that any more than they’ve done here?’ ” Fisher remembers. “He was really concerned about that.”

And while he never discussed possibilities like conducting geology on other planets, Faulkner has a suspicion that Jack would enthusiastically support the school’s work with NASA to explore other worlds.

“I would guess that he would be excited about the otherworldly geology that is being explored,” he said. “Jack had a venturesome mind. He loved geology, and he was interested in new things. He would want the school to be in a venturesome position, and I think he would be proud of that.”

Ultimately though, the consensus of those who knew Jack is that it would be the work done to improve the state by educating its future generations, and turning them into productive, successful citizens, that would make him smile the most. Several mentioned GeoFORCE Texas, which helps kids from underprivileged and underserved areas of Texas pursue a career and education in the geosciences, as the perfect example of Jack’s vision.

“Education is the equalizer. It will overcome all barriers. It is the one thing that will,” Langham said. “That’s what Jack believed. That’s why he gave his money.”

—————————————————————————————

We All Have A Part To Play

The permanent endowment left by Jack and Katie Jackson created a strong foundation for excellence. It enabled the Jackson School to hire top faculty and research scientists, and build state-of-the-art facilities that increase the depth and breadth of science conducted at the school and enrich student education.

But it was never meant to support the school exclusively.

The Jackson School relies on individual donors to ensure that it can continue its mission of conducting cutting-edge research and offering students a world-class education — just as Jack and Katie intended.

The endowment includes royalties from the estate’s wells and leases. And to honor Jack’s wishes, the Jackson School is the only institution in The University of Texas System that manages its own mineral rights. However, royalties can be significantly affected when gas and oil prices fall.

The Jackson School relies on thousands of individual stakeholders investing time, money and counsel at a range of levels to continue its path of excellence. Jack and Katie could think of no investment more valuable.

In Jack’s words: “We are investing in the future of a countless number of people at The University of Texas at Austin, who will study and will continue to learn of the geology, the earth sciences, and the resources and the environment of the Earth. I know of nothing more worthwhile.”

Back to the Newsletter