Slow Slip

November 2, 2015

Undetected by humans, slow motion earthquakes are happening all over the world. Understanding them could help predict when destructive quakes are coming.

By Monica Kortsha

Subduction zones — the places where one tectonic plate begins to descend beneath another — produce the largest and deadliest earthquakes and tsunamis on earth.

They’re also home to a subtler kind of seismic event.

Scientists have recently discovered a class of fault movements akin to earthquakes in slow motion occurring on subduction zones around the world. Called a “slow slip event,” the mechanics are similar to those of large earthquakes, but instead of releasing their energy in a few seconds of violent shaking, they happen silently and slowly over a period of days to months.

The only signs of slow slip events at the surface are centimeter-sized shifts in the land that cause it to relax and relieve some previously accrued tectonic stress. They remained hidden until 2001, when a GPS monitoring network deployed by Canadian scientists detected slight movements above the Cascadia subduction zone on the northwest coast of the United States and western Canada. Since that first discovery about 15 years ago, slow slip events have been observed around the world.

While imperceptible to humans, the gradual movements of slow slip events may hold major sway when it comes to more destructive seismic events. The 9.0 magnitude Tohoku-Oki earthquake that struck off the coast of Japan in 2011 and ultimately led to the nuclear disaster at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant was preceded by two slow slip events, one occurring three years and the other one month before the quake. Recent research has framed these events as the final straws that set the earthquake off.

On the flip side, it is also possible that slow slip events may relieve stress in earthquake zones and help to prevent such large quakes from happening.

Understanding when slow slip events could signal earthquakes, or potentially prevent them, starts with knowing when and where on the subduction zone they occur, said Laura Wallace, a researcher at the Jackson School of Geosciences Institute for Geophysics (UTIG).

Wallace has been studying slow slip events almost as long as anyone on the planet and is now taking her research to uncharted territory: the bottom of the ocean. Using under-water instruments that measure deformation of the seafloor during very shallow slow slip events, she hopes to understand just where along offshore subduction boundaries slow slip events happen.

Lada Dimitrova, a postdoctoral fellow at UTIG, will also play a key role in the research. She has developed a new method to analyze the onshore GPS data that provides a view of the spatial and temporal evolution of slow slip events in unprecedented detail.

Discovering Slow Slip

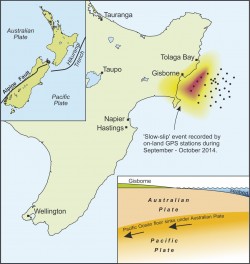

Wallace discovered the first slow slip events ever recorded in New Zealand while working at New Zealand’s geological research institute, GNS Science. One of her first tasks at GNS was to help design a continuously operating GPS network to monitor New Zealand’s Hikurangi margin subduction zone as part of the country’s GeoNet project, a geohazards monitoring system. Almost as soon as the network was live, slow slip started to appear, Wallace said. The first sign was a GPS site near the city of Gisborne, New Zealand, shifting by two centimeters eastward over 10 days in October 2002.

The jump eastward indicated a break in the ongoing tussle between the Australian Plate and the westward subducting Pacific Plate, with slow slip allowing the Australian Plate to slide back into a more relaxed state, like a released spring returning back to its unstretched state. A GPS device captured the period of gradual stress accumulation punctuated by episodic slow slip events at the Hikurangi subduction zone, and over time produced data with a telltale staircase-like appearance. When Wallace saw the first eastward jump in 2002, it immediately caught her attention.

“I looked at the GPS time series plots on the web and said, ‘Oh my gosh, that looks like a slow slip event,’ ” Wallace said.

The slow slip event didn’t show up on any of the GeoNet’s 10 other devices. There were only about a dozen GPS sites in New Zealand at that time, and they were too far from the GPS site at Gisborne that recorded the event. But data obtained from a local surveyor’s GPS base station also detected the event, proving that slow slip also occurs at New Zealand’s subduction zones.

Since then, the GeoNet GPS network has expanded to over 150 devices across the country and has revealed slow slip activity all along New Zealand’s Hikurangi subduction zone. In parts of the zone monitored by GeoNet, an event occurs about every 18 months, lasts one to two weeks, and causes displacement of up to three centimeters. Some of the recorded events are longer (up to 1.5 years), and have contained about the same amount of energy as a magnitude 7.0 earthquake, larger than the one that devastated Christchurch, New Zealand, in February 2011, killing 185 people.

However, the capability of GeoNet’s GPS monitors ends where the ocean starts. And the Hikurangi subduction zone extends 30 miles into the Pacific Ocean to its place of origin — a trench in the seafloor made by the Pacific Plate as it begins its descent beneath the Australian Plate. So, funded by the National Science Foundation, Wallace led a team of researchers on a 2014 mission that extended slow slip tracking capabilities into the ocean by dropping monitoring devices along parts of the subduction zone out of GeoNet’s reach.

Officially called the Hikurangi Ocean Bottom Investigation of Tremor and Slow Slip, the mission goes more frequently by its Tolkien-inspired nickname “HOBITSS,” a fitting choice for research based in New Zealand, the country where “The Lord of the Rings” movies were famously filmed. The mission brought together researchers from seven institutions in the U.S., Japan, and New Zealand, to drop 32 seismic and pressure-recording instruments to the bottom of Poverty Bay on the North Island’s southeastern coast.

Since deployment, the devices have been continuously recording movements and seismicity at the Hikurangi subduction zone, where slow slip occurs only five to 15 kilometers below the Earth’s surface. The data will provide the first comprehensive look at slow slip along the offshore reaches of a subduction zone, where the plate boundary nears the seafloor. Prior to now, studies of slow slip have been restricted to deeper slow slip events (greater than 20 kilometers beneath the earth) where land-based networks are able to detect them.

Between a Rock and a Hard Place

According to Wallace, the scientific community’s current understanding of why slow slip events occur and their relationship to large, damaging earthquakes is still in its infancy. But a working theory is that the slow slip environment is a transitional zone between two other subduction zone regions: the deeper aseismic zone where the plates move smoothly past each other without getting stuck, and the shallower seismic zone, where frictional hang-ups between the plates cause earthquakes.

“Many of the world’s slow slip event zones seem to straddle a transition between the area where earthquakes are produced, and the steadily creeping part,” Wallace said. “So it looks like slow slip may be related to some sort of transitional frictional behavior.”

Many studies also suggest that abundant water in slow slip zones may help build up high fluid pressures in the fault zone, and that this could promote slow slip behavior. It is likely that a combination of abundant fluids and the frictional properties of the rocks in seismic zones enables stress between plates to be released more gradually as slow slip events rather than as quick jolts that cause earthquakes.

Scientists are also interested in the relationship between slow slip events and more typical, “fast slip” earthquakes. There are clear spatial and temporal linkages between slow slip and earthquakes observed at many plate boundaries, including Japan, New Zealand and Cascadia, but these relationships are not yet well understood.

Since slow slip events are often observed along the boundaries of the area where large earthquakes happen, they may be useful for helping to forecast the locations of future large tremors.

“If slow slip does delineate the locked zone, you could potentially use the distribution of slow slip events as further evidence for where the big quake ruptures are going to be,” Wallace said.

DIY Engineering

Recording the slow slip events offshore rests on the ability of bottom pressure recorders, or BPRs, at the bottom of the ocean to detect subtle changes in pressure due to movement of the seafloor during the slow slip events. It is a new role for the devices that have previously been used in studies of tsunamis and submarine volcanoes.

For the HOBITSS experiment, UTIG built five BPRs. Anatoly Mironov, UTIG’s resident electronics engineer, is the man behind the design and construction of the devices.

“This is my specialty,” Mironov said. “All my life I have been designing different equipment.”

At UTIG, Mironov engineers scientific devices that need to be built or modified. He’s provided technical support for the ice-penetrating radar system used by UTIG researchers Donald Blankenship and Ginny Catania to survey features beneath Antarctica, and has built and upgraded many ocean bottom seismometers for various UTIG projects.

Mironov started his geophysics career in the former U.S.S.R, his homeland, as a technical leader in the Russian Arctic and Antarctic expeditions in 1985. It was in Antarctica where he met Blankenship and learned about UTIG, the institution he would join 15 years later.

“In Antarctica people really get to know each other,” Mironov quipped.

Each device Mironov makes comes with its own challenges. For the BPR, the main issues to be overcome were keeping the electronics running constantly for two years and keeping them dry. He learned first-hand about the challenges of the second point years ago when the casing for an ocean bottom seismometer he designed sprung a leak. He now keeps the device, its corroded and salt-crusted motherboard exposed, on his desk.

“It’s on my desk to remind me that there are no minor things when you design or prepare equipment for deployment,” Mironov said. “Any mistake, and you lose the instrument, you lose the data, and eventually many years of your work are thrown in the trash.”

Wallace’s BPRs underwent a strict sealing protocol inside a pressure-resistant case.

However, Wallace and Mironov won’t know the state of the devices and their data until they’re retrieved.

Bringing the BPRs back is also a risky task that depends on all of the components working properly. A release code transmitted to a BPR makes it drop anchor and float to the surface, while a radio beacon, a strobe light and old-fashioned flag on the BPR help guide researchers to it. And just in case someone else finds it first, Wallace’s contact information is on each device, too.

Recovery at Sea

At the time this article was written, Wallace, Mironov and other members of the HOBITSS research team had recently recovered the data from the BPRs at the bottom of the sea. Although it will take months to analyze the data, the initial results look promising, Wallace said.

“I am really excited to say that we have recovered our instruments, and that the vast majority of them have great looking data,” Wallace wrote in a blog post for the HOBITSS cruise.

The data recovered from the devices’ first year along the subduction zone will help determine where slow slip events occur on the shallowest reaches of the subduction zone plate boundary. The BPR and ocean bottom seismometer data together will help scientists to better understand the spatial and temporal connection between slow slip and earthquakes.

The data will also help pinpoint the areas of interest for Wallace’s next research project along the Hikurangi subduction zone: drilling near the plate interface itself.

Wallace is part of a large international team of scientists that is scheduled to use the Integrated Ocean Drilling Program’s research vessel JOIDES Resolution in 2018 to investigate the causes of shallow slow slip events offshore New Zealand. They will take core samples from the plate boundary surrounding the slow slip area, and install borehole instruments, such as pressure gauges and fluid flow sensors.

“We’ll be monitoring hydrological changes, deformation rate changes, and fluid chemistry changes to try and look at how these properties vary throughout the slow slip cycle,” Wallace explained.

In the meantime, while the research team parses data and drilling plans are set in motion, slow slip events will continue to shift subduction zone landscapes at a rate only GPS — and now HOBITSS — can notice.

Back to the Newsletter