Drought & Deluge

November 2, 2015

Water is the most precious resource on Earth, but there always seems to be too little or too much of it in Texas. Research at the Jackson School is tackling the challenges posed by these extremes.

By Anton Caputo

In 2011 most of Texas was gripped by a brutal drought that rivaled the worst in the state’s recorded history. Rivers and streams dried up, and reservoirs fell to record lows. Farmers and ranchers were devastated, and some communities were forced to take expensive emergency measures to ensure their citizens had water until heavy rains finally broke the drought in 2015.

At the same time as the drought, deadly floods periodically ravaged communities, with some occurring in the most parched areas of the state.

Providing water during droughts and dealing with floods is challenging in a fast-growing, geographically diverse state like Texas. The Jackson School of Geosciences is working on solving these issues with wide-ranging research. The methods include new forecasting techniques, intricate climate models, studies to determine how to better store water underground and projects to measure water more accurately from space.

The overarching goal is to provide the tools and knowledge to better manage this precious resource.

“This is the type of science that will benefit people throughout the state and beyond,” said Jackson School Dean Sharon Mosher. “This work fits in perfectly with the school’s mission: to advance understanding of the Earth, its resources, systems and environment, for the lasting benefit of humankind.”

Under Our Feet

It’s not hard to understand why 2011 devastated the state’s water supply. The blistering summer was the hottest and driest in Texas history. On average, only 14.89 inches of rain fell that year, beating a low mark set in 1917. October 2010 through September 2011 was the driest period ever on record, with average rainfall of only 11.18 inches.

The scorching weather drove up water demand. There were 90 days of 100 degrees or more recorded in Austin that year and 71 recorded in Dallas. And the lack of rain only exasperated the issue. As a result, rivers and streams dried up, and reservoir levels plummeted.

The rains returned more or less to normal in much of the state in 2012 and 2013, but it didn’t seem to help the rivers or reservoirs much, which puzzled and frustrated many Texans. Todd Caldwell, a researcher at the Bureau for Economic Geology, sums up the reason why water sources remained low in two words: soil moisture — or more accurately, the lack of it.

Simply put, parched soil can soak up a lot of rain water before it runs off into lakes and rivers or recharges aquifers.

“Soil is like a sponge,” Caldwell said. “When it’s dry, you can drip a lot of water on it before it starts to drip out the sides.”

But once that soil is filled to capacity, rain will run off quickly, sometimes with disastrous effects as happened in the deadly flooding in Austin in 2013 and in Wimberley in 2015.

“Wimberley received 6 to 8 inches of rain in the watershed that day, which is a lot of rain, but it’s happened before [without flooding],” Caldwell said. “But that 6 to 8 inches came after it had rained consistently for several months. It just kept building up and building up [in the soil] and all of a sudden it was full. The intensity of this flood was really linked to soil moisture.”

Because soil plays such an important role in water supply and floods, the Bureau of Economic Geology created the Texas Soil Observation Network (TxSON), a network of underground sensors in the Texas Hill Country designed to measure the moisture in the soil and upload the data online for anyone to view. The system became fully operational in December 2014.

The data can help fill a tremendous gap in the state’s water supply knowledge, Caldwell said. For example, university researchers estimate that there was a total water deficit in Texas in 2011 of 50 million acre-feet, nearly three times the annual water use of the entire state. (An acre-foot of water is the amount needed to fill one acre of land with one foot of water.) The amount of the 2011 shortage accounted for by soil moisture was estimated to be anywhere from 20 percent to 100 percent, a range that highlights the uncertainty in knowledge.

Currently, the network consists of 36 soil moisture monitoring stations that are supplemented by seven stations from the Lower Colorado River Authority’s Hydromet system that have been outfitted with soil moisture sensors. Caldwell is looking to increase that number and has become something of an evangelist for the system. He’s been on the road for much of the past year looking for partners, talking to river authorities, water districts, utilities and others interested in water supply.

Participants include the Hill Country Underground Water Conservation District, the Blanco-Pedernales Groundwater Conservation District, Lower Colorado River Authority and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL).

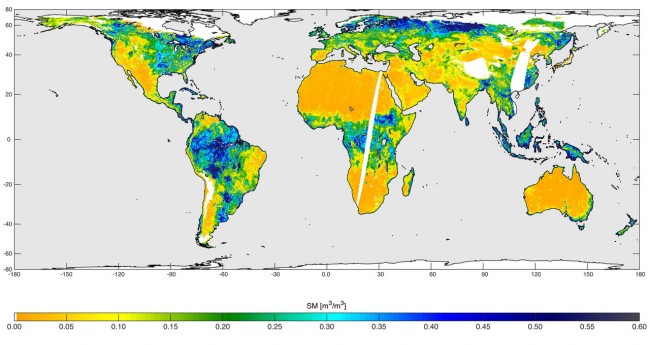

JPL partnered with TxSON to ground truth its new state-of-the-art Soil Moisture Active Passive (SMAP) satellite, launched Jan. 31, 2015. The satellite measures soil moisture worldwide every three days, providing data that will enhance the ability to predict weather on a global scale days or weeks ahead of time and improve forecasts of drought, floods, wildfires and severe weather.

“The water that’s stored in the soil can either exacerbate or mitigate dry or wet weather,” Caldwell said. “The amount of water near the Earth’s surface either consumes or radiates the sun’s energy. If there’s moisture, water evaporates and the land doesn’t heat up. If there isn’t, the land and air warm up, causing the winds to blow and water vapor to move. If we know the amount of water, our weather forecasts can really be improved.”

The satellite measures water in the top two inches of soil with a radiometer that measures radiation emitted by the soil. SMAP was also outfitted with a radar sensor, but that equipment is no longer working after it malfunctioned in July 2015.

Understanding Fundamentals and Predicting the Future

Even with the assistance of satellites, forecasting what’s going to happen to the water on Earth is a difficult task. Scientists spend years building complex computer models to make predictions and then years more to improve them, fine tuning the science to better understand how water cycles through the land, ocean and atmosphere.

“This is fundamental,” said Jackson School Professor Zong- Liang Yang, Director of the Center for Integrated Earth System Science (CIESS). “Understanding these connections can directly be translated to the predictive skill we build into models.”

Yang’s group of graduate students, postdocs and research scientists specializes in models that help monitor water resources, predict floods and droughts, and improve the understanding of water-cycle mechanisms. Their work has been used by leading national centers including the National Center for Atmospheric Research and National Centers for Environmental Prediction, but much of the group’s efforts are also directly aimed at improving knowledge of the Texas water supply.

The group is currently developing a model to more accurately predict seasonal streamflow throughout Texas, which could greatly improve water supply forecasting. They are also working to determine where the rain in Texas originates.

So far, their analysis shows that the Gulf of Mexico is the largest contributor, providing nearly 46 percent of the state’s rainfall over an average year. The Eastern Pacific Ocean is second with more than 17 percent, and Mexico and Latin America are third with almost 12 percent combined.

But the situation is not static. For example, Jiangfeng Wei, a research scientist working with Yang has found that the percentage of rainfall in Texas that originates in the Eastern Pacific grows significantly in the colder months. With more research, this type of fundamental knowledge about moisture cycling can help predict floods and droughts, Yang said.

“You want to understand how the atmosphere is connected to oceans and connected to the local hydrology because the models we develop are based on the interactions between these different components,” he said.

But even the best models have their limitations.

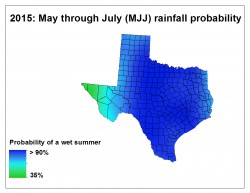

For instance, large-scale climate models are no more accurate than a coin toss at predicting rainfall in Texas in the late spring and early summer months — a time period that’s essential for influencing how a summer drought will play out. A good rain can keep the state from turning into a dustbowl, while dry, hot months can turn a mild drought into a severe one, as it did in 2011.

But the odds are getting better thanks to research conducted by Jackson School Professor Rong Fu and former Jackson School postdoc Nelun Fernando, who is now working with the Texas Water Development Board.

Their new prediction method boosts the accuracy of rain prediction to about 70 percent, with work ongoing to improve that number.

The new method is a statistical forecast model that uses more localized data — like atmospheric pressure and land surface conditions — than the larger-scale dynamic climate models.

“That’s because in summer the rainfall is determined by more local, smaller-scale processes,” Fu said.

The localized model also uses historical data on Texas weather to help inform rainfall predictions.

“We can show that there is an empirical relationship between spring drought conditions and summer drought that gives a better prediction than the dynamic model,” Fu said.

The team successfully tested the new method in 2014. In 2015, with the prediction enhanced with measurements from the SMAP satellite, the forecast showed that most of the state had a high likelihood for greater than average rainfall. This was proven correct when heavy rain swept across much of Texas during that period, ending the drought.

The Water Development Board is making the new forecast available to water utilities, water managers and decision makers. Fu said the team will work to make the predictions more accurate and available earlier in the year if funding can be secured.

Living with Reality

No matter how good scientists get at predicting the future, Texas is going to have to learn to live through extreme dry spells, said Bridget Scanlon, who leads the bureau’s Sustainable Water Resources Program.

Because of the booming population, reservoir capacity per capita has fallen by 70 percent in Texas since the 1970s. There are some new off-channel reservoirs being built in Texas, but it would be extremely challenging to expand surface reservoir capacity enough to cope with these extremes, she said.

“It’s very difficult to get a permit to build any new surface reservoirs, and the prime sites for reservoirs have already been taken,” Scanlon said.

The future will likely entail a variety of water supply solutions. A strategy that Scanlon champions is aquifer storage and recovery. This entails moving water during wet times into partially depleted underground aquifers, where the water is stored for use during droughts. (For more information, see Scanlon’s op-ed on page 20, titled “Don’t let Texas excess water go to waste.”)

She is also working with the Texas Water Development Board to look at the potential of capturing water flowing down the rivers to the Gulf of Mexico during floods and using it for water supply.

Scanlon has spent years studying drought throughout the world, particularly in Australia, which endured roughly 15 years of crippling drought starting in the mid-1990s. She has also worked in California recently, which is in the middle of one of its most severe droughts on record. Both hold hints at what the future may hold for Texas.

“In the future we are going to have to consider all possible water sources,” Scanlon said. “Look at what L.A. is doing now — using stormwater, municipal wastewater, imported water, storing water in aquifers. Having a much broader portfolio increases drought resilience.”

Back to the Newsletter