Back from Totten

October 22, 2014

Unbreakable ice alters research plans for UTIG researchers

By Terry Britt

Even when uncontrollable circumstances keep an expedition from reaching its intended landmark, it does not mean the participants come away empty-handed.

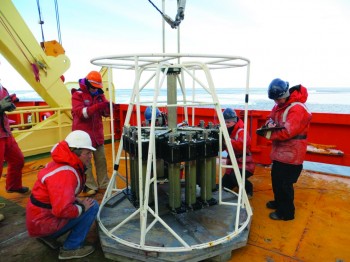

Such was the case for those involved in the Totten Expedition, a collaborative scientific research voyage into East Antarctica for about six weeks in February and March 2014. Sean Gulick, an associate research professor at the University of Texas at Austin’s Institute for Geophysics (UTIG) explained that the icebreaker vessel on which they were sailing was unable to get through ice that blocked the way to the Totten Glacier.

“Icebreakers, despite their name, can’t break all kinds of ice,” Gulick explained. The researchers’ ship, the R/V Nathaniel B. Palmer, tried three times to get to the Totten Glacier. On one attempt, it took almost three hours for the ship to turn back once it became obvious that passage could not be gained.

Interestingly, though, as the research team explored the systems en route to Totten, they realized it’s all one big system. “We didn’t get to the main trunk, which was where Totten comes out of, but we saw a lot of the feeders and saw a part that was probably the second most important, if you will, pathway,” Gulick said.

Fellow UTIG researcher Steffen Saustrup noted the area the expedition was able to reach yielded very valuable data itself.“

Gradually that secondary area became more and more interesting to us and actually became of real value. It was almost an accidental data set. The regrettable thing is the time lost attempting to get to Totten. The value of an hour’s worth of data is great,” Saustrup said.

Gulick said there were actually three areas of discovery in a part of the Antarctic that “effectively had never been explored by ship.”

“Fundamentally, we were able to map the seafloor, and in a place where we didn’t even know how deep the water was, and observe some sort of dynamic processes of glaciers that occurred during the last great retreat of the Antarctic ice sheet,” Gulick said.

What the researchers found is that the ice sheets and glaciers in East Antarctica are thinning more rapidly than previously thought.

“A lot of people were aware the glaciers and ice sheets are retreating back because you can see that with satellite imagery,” Saustrup said. “What I didn’t know coming into this is they are thinning even faster than they are retreating back in places so the total volume loss of ice is greater than I realized, because I’m not a glaciologist.”

“The question now becomes why they are thinning as well as retreating, and thinning faster than predicted by models just based on air temperature, sunlight and things like that,” Saustrup said.

UTIG researcher Rodrigo Fernandez-Vasquez added about the significance of the expedition’s findings, “Now we know there are several glaciers below sea level and this (Totten) is one of those. That was the main hook for this research. This is one of the places in East Antarctica that … is more unstable than we think.”

David Gwyther, a University of Tasmania Ph.D. student currently completing a Fulbright scholarship at the university, elaborated on the changes taking place.

“This is the region in East Antarctica that is showing the greatest change. It’s the glaciers that have very deep grounding lines so that the glacier starts to float. If we look at areas of thinning, they are also the areas that have these deep grounding lines and there is probably warm water coming in. The theory is the ocean is changing and driving this increased thinning,” Gwyther said.

He said the research on the expedition provided a nice confirmation of three years of modeling work about the area.

“The head oceanographer wanted to do a map of temperature and salinity. We did that and put some of the measurements taken at the same depth, and the model predictions were spot on with what we were measuring,” Gwyther said.

Back to the Newsletter