Scientists Find Evidence for “Great Lake” on Europa and Potential New Habitat for Life

November 16, 2011

![]() Watch animation of how lakes form inside Europa’s icy shell.

Watch animation of how lakes form inside Europa’s icy shell.

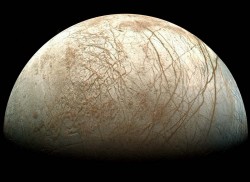

In a significant finding in the search for life beyond Earth, scientists from The University of Texas at Austin and elsewhere have discovered what appears to be a body of liquid water the volume of the North American Great Lakes locked inside the icy shell of Jupiter’s moon Europa.

The water could represent a potential habitat for life, and many more such lakes might exist throughout the shallow regions of Europa’s shell, lead author Britney Schmidt, a postdoctoral fellow at The University of Texas at Austin’s Institute for Geophysics, writes in the journal Nature.

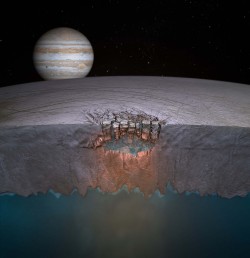

Further increasing the potential for life, the newly discovered lake is covered by floating ice shelves that seem to be collapsing, providing a mechanism for transferring nutrients and energy between the surface and a vast ocean already inferred to exist below the thick ice shell.

“One opinion in the scientific community has been, ‘If the ice shell is thick, that’s bad for biology — that it might mean the surface isn’t communicating with the underlying ocean,’ ” said Schmidt. “Now we see evidence that even though the ice shell is thick, it can mix vigorously. That could make Europa and its ocean more habitable.”

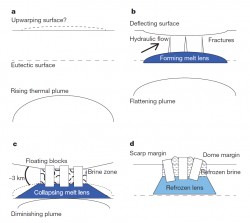

The scientists focused on Galileo spacecraft images of two roughly circular, bumpy features on Europa’s surface called chaos terrains. Based on similar processes seen here on Earth — on ice shelves and under glaciers overlaying volcanoes — the researchers developed a four-step model to explain how the features form on Europa. It resolves several conflicting observations, some of which seemed to suggest that the ice shell is thick and others that it is thin.

“I read the paper and immediately thought, yes, that’s it, that makes sense,” said Robert Pappalardo, senior research scientist at NASA’s Planetary Science Section who did not participate in the study. “It’s the only convincing model that fits the full range of observations. To me, that says yes, that’s the right answer.”

The scientists have good reason to believe their model is correct, based on observations of Europa from the Galileo spacecraft and of Earth. Still, because the inferred lakes are several kilometers below the surface, the only true confirmation of their presence would come from a future spacecraft mission designed to probe the ice shell. Such a mission was rated as the second-highest priority flagship mission by the National Research Council’s recent Planetary Science Decadal Survey and is currently being studied by NASA. On Earth, radar instruments are used to image similar features within the ice, and are among the instruments being considered for a future Europa mission.

“This new understanding of processes on Europa would not have been possible without the foundation of the last 20 years of observations over Earth’s ice sheets and floating ice shelves,” said Don Blankenship, a co-author and senior research scientist at the Institute for Geophysics, where he leads airborne radar studies of Earth’s ice sheets.

Schmidt and Blankenship’s co-authors are Wes Patterson, planetary scientist at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, and Paul Schenk, planetary scientist at the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston.

The research was funded by the Institute for Geophysics at The University of Texas at Austin’s Jackson School of Geosciences, the Vetlesen Foundation and NASA.

The paper, “Active formation of ‘chaos terrain’ over shallow subsurface water on Europa,” will appear as an advance online publication of the journal Nature on Nov. 16.

Videos

![]() Watch animation of how lakes form inside Europa’s icy shell.

Watch animation of how lakes form inside Europa’s icy shell.

![]() NASA Press Briefing (Nov. 16, 2011)

NASA Press Briefing (Nov. 16, 2011)