Severity, Length of Past Megadroughts Dwarf Recent Drought in West Africa

April 16, 2009

Droughts far worse than the infamous Sahel drought of the 1970s and 1980s are within normal climate variation for sub-Saharan West Africa, according to new research.

For the first time, scientists have developed an almost year-by-year record of the last 3,000 years of West African climate. In that period, droughts lasting 30 to 60 years were common. Surprisingly, however, these decades-long droughts were dwarfed by much more severe droughts lasting three to four times as long, scientists report in the 17 April issue of the journal Science.

According to a 2002 report by the United Nations Environment Program, the most recent Sahel drought killed more than 100,000 people and displaced many more.

“What’s disconcerting about this record is that it suggests that the most recent drought was relatively minor in the context of the West African drought history,” said first author Timothy M. Shanahan, an assistant professor of geosciences at The University of Texas at Austin.

The research team determined the region’s past climate by analyzing the annual layers of sediment deposited in Ghana’s Lake Bosumtwi, geological records of the lake level and other climate indicators, including submerged forests, which grew around the lake during past droughts when the lake dried up for hundreds of years.

“If we were to switch into one of these century-scale patterns of drought, it would be a lot more severe, and it would be very difficult for people to adjust to the change,” said Shanahan, who conducted the research while he was a doctoral student at the University of Arizona in Tucson.

As global warming progresses, the increases in temperature may exacerbate the normal climate pattern, producing even more severe and prolonged droughts than those of the past, said co-author Jonathan T. Overpeck, a University of Arizona professor of geosciences.

“We know that Africa gets long, bad droughts,” said Overpeck, co-director of the university’s Institute for Environment and Society. “We also know that global warming will make these droughts a lot hotter. This could be devastating.”

The cause of the anomalously long periods of drought?

Their research suggests that changes in sea surface temperatures of the Atlantic Ocean play a key role in sustaining drought over this region for decades to centuries, supporting other recent research using climate models. On 30- to 60-year intervals, sustained periods of wet and dry conditions appear to be directly linked to a hypothesized mode of climate variability termed the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation. Because long, high resolution records of ancient climate from the Atlantic are sparse, the existence of such a mode has been questioned by scientists.

“This paper provides a long-term context suggesting that the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation does actually exist,” said Shanahan. “Our rainfall records are strongly related to these really distant sea surface temperature reconstructions, at least on this multidecadal time scale. It suggests that the rainfall patterns are being generated by the sea surface temperature patterns and not by some other influence.”

Armed with this new information, scientists who create climate models will be better equipped to sort out some of the conflicting climate predictions for West Africa. Some climate models have forecast wetter conditions for West Africa while others have forecast drier conditions. The results of this study highlight the susceptibility of this system to sustained dry conditions, and suggest that historical records from the past century do not capture the severity of natural droughts that have been common over the last few millennia.

“To reduce uncertainties, current climate models need more data from both high- and low-latitude field work, and from periods that extend back well beyond the instrumental record,’ said Paul Filmer, program director at the National Science Foundation. “This project is a good example of how work in the tropics on sediment records provides more detailed insight into climate patterns that affect millions of people in a highly vulnerable area of the world.”

Shanahan, Overpeck and their colleagues will publish their findings in the paper, “Atlantic forcing of persistent drought in West Africa.” Shanahan and Overpeck’s University of Arizona co-authors are J. Warren Beck, Julia E. Cole and David Dettman. Researchers from Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory in Palisades, N.Y., the University of Akron, Syracuse University, the University of Rhode Island, Nkrumah University of Science and Technology in Kumasi, Ghana, and the Ghanaian Geological Survey also participated. The National Science Foundation funded the research.

More Information

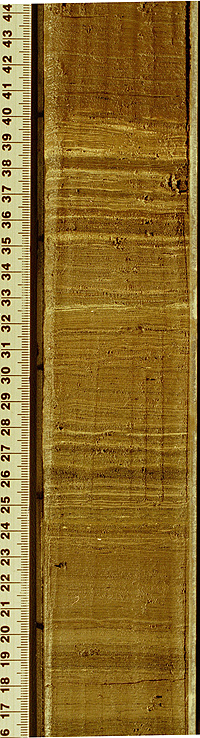

To reconstruct the monsoon cycle, the scientists took core samples of sediments in Lake Bosumtwi, a 10-kilometer (6 mile) wide meteorite impact crater in Ghana. The team used several dating techniques—including radiocarbon dating, lead-210 dating, and a tell-tale carbon14 trace from nuclear weapons testing in the 1950s—to confirm that the lake’s sediments form annual layers.

The researchers measured the concentrations of various elements in each layer to determine annual lake levels and, by extension, rainfall. Measuring oxygen isotopes in the sediment layers independently confirmed that the reconstruction is valid.

Lake Bosumtwi, about 80 meters at its deepest, turns out to be the best place in West Africa to obtain this type of climate record, Shanahan said. Because only the top 15 meters or so of water have enough oxygen to support fish and other large aquatic life forms, most of the lake bottom remains undisturbed, allowing sediment deposits to form in discrete layers.

Shanahan worries that our current period of greenhouse warming might drive the atmosphere-ocean system into a centuries-long drought mode, which would have unprecedented effects on rapidly expanding populations in sub-Saharan Africa who depend heavily on monsoon rainfall for agriculture and power generation.

For more information about research at the Jackson School, contact J.B. Bird at jbird@jsg.utexas.edu, 512-232-9623.