How the Gulf Dodged Mass Extinction

December 5, 2022

An ancient bout of global warming 56 million years ago that acidified oceans and wiped out marine life had a milder effect in the Gulf of Mexico, where life was sheltered by the basin’s unique geology, according to research by the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics (UTIG).

Although the Gulf of Mexico of the present is very different from that of the past, the study offers valuable lessons about modern climate change, said the study’s lead author, UTIG geochemist Bob Cunningham.

“This event known as the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum, or PETM, is very important to understand because it’s pointing towards a very powerful, albeit brief, injection of carbon into the atmosphere that’s akin to what’s happening now,” he said.

The findings were published in the journal Marine and Petroleum Geology in April 2022.

Cunningham and his collaborators investigated the ancient period of global warming and its impact on marine life and chemistry by studying a group of mud, sand and limestone deposits found across the Gulf. They concluded that a steady supply of river sediments and circulating ocean waters had helped microorganisms survive even while Earth’s warming climate became more hostile to life.

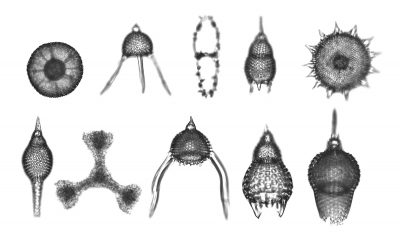

The findings also confirm that the Gulf of Mexico remained connected to the Atlantic Ocean, and the salinity of its waters never reached extremes — a question that until now had remained open. This conclusion was reached in part by geologic samples containing radiolarians, a type of microorganism that only thrives in nutrient-rich water that’s no saltier than seawater today.

The research also accurately dates closely related geologic layers in the Wilcox Group (a set of rock layers that house an important petroleum system). This information can aid in efforts to find undiscovered oil and gas reserves in formations that are the same age.

The research relied on geologic samples from 36 industry wells dotted across the Gulf of Mexico, plus a handful of scientific drilling expeditions. For John Snedden, a study co-author and senior research scientist at UTIG, the study is a perfect example of industry data being used to address important scientific questions.

“We’ve used this very robust database to examine one of the highest thermal events in the geologic record, and I think it’s given us a very nuanced view of a very important time in Earth’s history,” he said.

Back to the Newsletter