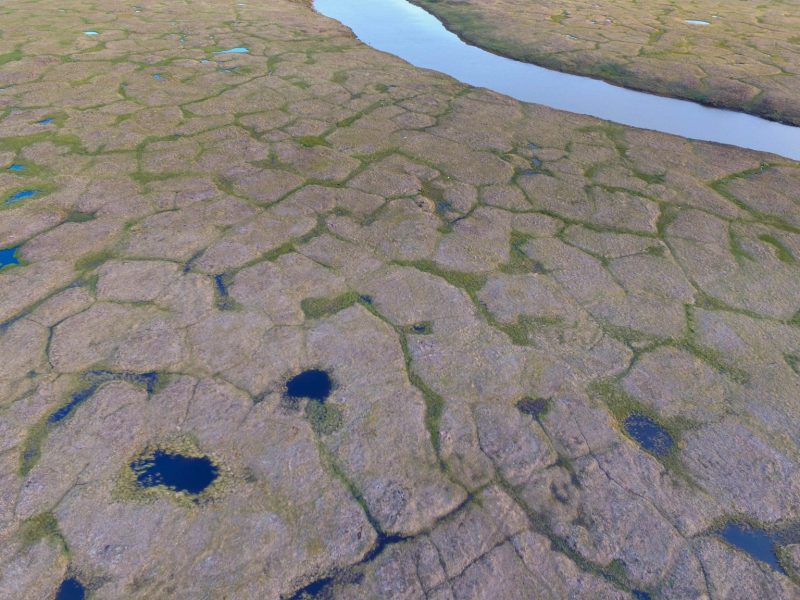

Alaska’s Rapidly Thawing Coastal Permafrost

October 29, 2021

Scientists have long believed that permafrost in cold climates doesn’t just stop where it meets the sea: It should extend from the tundra to below the seafloor.

However, research led by Micaela Pedrazas, who earned a master’s degree at the Jackson School of Geosciences working with Professor Bayani Cardenas, has upended that paradigm. They found permafrost to be mostly absent throughout the shallow seafloor along a coastal site in northeastern Alaska. That means vast amounts of carbon can be released from coastline sources much more easily than previously thought. The study was published in Science Advances in October 2020.

The researchers examined the subsurface beneath Alaska’s Kaktovik Lagoon. Their results were unexpected. The beach and seafloor were entirely ice-free down to at least 65 feet. On the tundra, ice-rich permafrost stopped just below 16 feet.

As permafrost melts, it releases stores of methane and carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, contributing to climate change. The melting permafrost also has local impacts for Indigenous communities along the coast. As the permafrost thaws, it accelerates coastal erosion, which carves away at the land on which homes and infrastructure stand. In the Kaktovik region, erosion can be as great as 13 feet per year.

“Their cultural heritage and their welfare are integrated and intricately linked to their environment,” Cardenas said. “There’s an immediate need to understand what’s happening in these lagoons.”

The Kaktovik Inupiat Corporation and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service provided permissions and support for the research.

ause of its ability to efficiently bring together sections of heterogeneous lithosphere along plate boundaries.

This article is adapted from a piece originally published in EOS.

Back to the Newsletter