Understanding the Shale Boom

November 2, 2015

Research at the Jackson School of Geosciences Bureau of Economic Geology (BEG) into U.S. shale oil gas production and reserves is widely considered to be the most comprehensive public study of its kind. Funded by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, a philanthropic nonprofit for supporting science, the bureau’s ongoing research into the six major shale plays in the country has become an invaluable resource for government, industry and fellow academics alike who hope to learn more about a subject that is vitally important to the country and the world.

The interdisciplinary approach taken by The University of Texas at Austin team of geologists, economists and engineers is unique in terms of its depth and complexity. It presents the potential of U.S. shale production on several levels.

Four years into the study, the group has become increasingly adept at uncovering how shale plays may shape the future of the U.S. energy story. Now stakeholders from across the country and the world are seeking insight from the BEG’s work.

We sat down with BEG Director and Principal Investigator (P.I.) Scott Tinker, and BEG Energy Economist and Co-P.I. Svetlana Ikonnikova, to find out what makes this study so important.

SO HOW DID THE SLOAN STUDIES COME ABOUT?

Scott Tinker (ST) – It was really the brainchild of environmental scientist Jesse H. Ausubel of The Rockefeller University. Ausubel was the first to map the transition in energy fuels from carbon-based entities such as hay, wood and coal, to complex hydrocarbons such as petroleum, to simple hydrocarbons like methane, eventually to a hydrogen economy generally. Jesse called this decarbonization.

Jesse understood before anyone else how important natural gas (methane) was going to become from an energy perspective in the future. He contacted me and Bill Fisher, professor and inaugural dean of the Jackson School, several years ago and asked if the bureau would be interested in considering a research program in methane. That was a very easy question to answer!

We started by organizing a couple of informal workshops and bringing together leaders from industry, government and academia to see what people already knew and where the gaps in knowledge about future resources were. From these workshops it became apparent pretty quickly that we didn’t understand shale and our shale reserve future all that well. It was also clear the country at large could benefit a lot from a detailed analysis. After a few months of fine tuning, we put in a funding proposal to do a study focusing on the Big Five gas basins: the Barnett, Fayetteville, Haynesville, Marcellus, and Eagle Ford shale plays (a sixth — the Permian Basin — was added later).

WHY DID YOU CHOOSE THOSE BIG FIVE?

Svetlana Ikonnikova (SI) – At that time, the shale gas resource was still quite new. There was a lot of speculation over the resource and the potential of different plays. Could it be a game changer? Nobody knew for sure. All we knew was that those five plays had already been producing significant shale gas and were growing. There was not much information and research publicly available. So it took us a few months to fine-tune our funding proposal. We had to go back to basic questions like: how much exactly is underground, what are the technologies to extract it, and what could be the key variables affecting future production?

YOU HAVE DESCRIBED YOUR METHODOLOGY AS A ‘BOTTOM UP’ RATHER THAN A ‘TOP DOWN’ APPROACH. WHAT EXACTLY DOES THAT MEAN?

ST – A ‘Top Down’ approach would be to assign a well production value to all the wells in a fairly large area based on an overall average performance, with some assumptions about cost and price. In contrast, we took a ‘Bottom Up’ data-driven approach.

We mapped the geology using logs and core data. Then, we looked at every single well in each field trying to predict each well’s future decline. Most of our data was gathered through IHS [formerly Information Handling Services] and Drillinginfo, who both kindly gave us access to their data. Combining geologic attributes and decline estimation for each well, we differentiated geographic areas by their productivity, creating so-called ‘tier maps.’ Hence, rather than simply showing core and non-core areas, we identify areas ranging from highly productive to poorly productive on a square-mile basis. Each of the fields is really quite heterogeneous. We then run an analysis that adds future wells into the undrilled ‘white space’ in the field using estimated well productivities from our tier maps. In other words, we take all the data from the bottom and aggregate it up. From that we run the future production scenarios for each play.

SI – With each play our methodology evolves. In the Marcellus study, we differentiate productive areas taking into account more details about well completion, such as lateral length and water used in hydraulic fracturing, that were not incorporated in the original Barnett, Fayetteville and Haynesville studies. In the current low energy price environment, cost management becomes an important part of the analysis. So we use details about completions, factoring in the cost. Prices may vary, and operators may react by changing their completion strategies. So we can’t simply forecast the future. What we can do, however, is run a set of scenarios with respect to economic and technical assumptions, informing about a range of uncertainties in future production. We designed a model that feeds in the geologic, engineering and economic field data, assumptions, and descriptions to explain how future play development may unfold.

SO WHERE DID YOU FIRST APPLY THIS NEW APPROACH?

ST – It is ironic, but we started with the Barnett Play, which coincidentally had been developed mostly by George Mitchell, the father of fracking. Mitchell got his original land position in the Barnett from a fellow by the name of Jack Jackson. You can’t make this up! So here we were working on something, which in the first instance would be a valuable study with a positive societal impact, but which might also provide increased royalties to the Jackson School of Geosciences through increased production. It all made sense.

THE BEG SLOAN STUDY TAKES AN INTERDISCIPLINARY APPROACH. YOU HAVE ECONOMISTS, PHYSICISTS, GEOLOGISTS AND ENGINEERS ALL COLLABORATING. COMING FROM SUCH DIVERSE BACKGROUNDS, HOW DOES THAT WORK?

ST – Better now than it did five years ago, that’s for sure! The group is varied, not just in terms of our academic backgrounds. We are fortunate to have a diverse team in terms of gender, nationality, culture and education as well.

But from the technical side of things there were some challenges. In our very early meetings we’d sit around the table scratching our heads. Each discipline basically has its own language. Over time we saw how collaboration could work. Now it has evolved in the right way. For each new basin we study, our understanding of the geology, engineering and economics gets deeper and more robust and we have a much clearer understanding of our roles.

ON THAT POINT, AS YOU LEARN MORE FROM EACH NEW PLAY STUDIED, DOES IT INFORM YOU ABOUT GAPS IN UNDERSTANDING FROM PREVIOUSLY STUDIED PLAYS?

SI – Each basin has added to our understanding and integration, such that now after our analysis of the Marcellus Play, we feel a strong need to take what we’ve learned there and reapply it to a second pass through the first three basins.

WHAT IS HAPPENING THAT REQUIRES THESE REVISIONS OF EACH PLAY SO SOON AFTER YOU COMPLETE A STUDY?

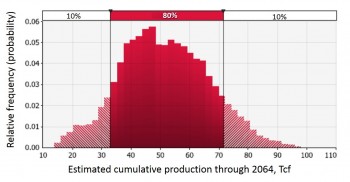

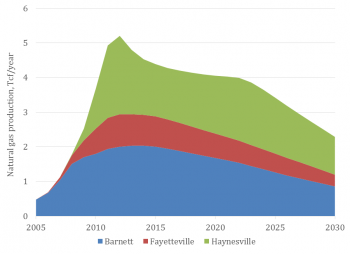

Figure 2. A “base case” scenario illustrating aggregated expected production from the Barnett, Fayetteville and Haynesville shale plays (modified from Ikonnikova et al., 2015).

SI – This is an incredibly dynamic sector. Technology and hydraulic fracturing practice are advancing rapidly and even more so in times of low prices. So, no sooner than one study has been finished, we find some of the approaches we applied in previous plays have alreadybecome too simplistic and are not suitable given the newly emerged practices.

We have looked back at plays like the Barnett and found that technology and performance and development pace have evolved. When we go back to check our work, we see some variables have changed and others now become more prominent owing to economic and technological advances. For instance, in the older plays, like the Barnett, operators apply infill drilling; in newer, like Fayetteville, cluster drilling. Both affect the number of future locations, well economics and, ultimately, field production.

AND WHAT ABOUT THE DIFFERENCES IN EACH PLAY, GEOGRAPHICALLY, GEOLOGICALLY AND ECONOMICALLY?

SI – We have had mini crises each time we begin a new study because our usual approaches need refinement to fully describe the new play. But the more we work in different areas, the more important it becomes to take into account additional variables. Operating practices can vary. The geology itself can also be different, in terms of porosity and rock information. Once we figured out how to factor in all this new info, through statistical analysis, we were able to identify the key drivers of production in each play. Making all those connections has been a true revelation to us. Suddenly we can see in great detail how all these factors connect.

SO WHY IS THIS INFORMATION USEFUL?

SI – The study offers a set of key parameters and variables that should be considered before any decision to drill. We are currently developing an online tool to show people what we do. This is not just about estimating one value or a simple figure for each well’s potential. The study is about more than just price. Never before has there been this much detail available to the burgeoning shale gas industry.

THE STUDIES HAVE ALSO GARNERED A LOT OF MAINSTREAM MEDIA ATTENTION, BOTH NATIONAL AND INTERNATIONAL. WHY DO YOU THINK THIS IS OF INTEREST TO THE GENERAL PUBLIC?

ST – This kind of detail is useful to anyone who uses energy, which by the way, is every single one of us. The public is interested because we all benefit tremendously through enhanced energy security and more affordable natural gas. We have found international, national and state governments are interested, as well as industry and other academics. The study is informing the people who need to make decisions in energy and related sectors of the economy.

We have been contacted by about a couple dozen public and private power producers in the last two years alone.

Even many environmental NGOs are interested. They need to understand what the reality of future energy fuels and resources look like before they try to inform government regulatory policies.

WHY ARE FOREIGN GOVERNMENTS AND ENERGY PRODUCERS INTERESTED?

ST – Shale gas resources can be found in basins all over the world, even in places that currently have no domestic energy production of their own. So there are opportunities for others to play in this brave new world just like us.

Those whose current economic condition is bolstered by selling inexpensive conventional natural gas, like Russia and the Middle East, aren’t as keen on shale gas…yet. Today it interferes with their margins selling more affordable conventional gas into markets. However, other regions like Australia and South America would love to see their shale developed. And down the road, Russia and the Middle East will develop their source rocks as well.

SO WHAT’S NEXT FOR THE BEG SLOAN STUDIES?

SI – We will be publishing our results from the Marcellus Play in the next six months. In the meantime we are completing the Eagle Ford and starting the Bakken Play analysis.

Then, we will also be looking west: the BEG intends to study the biggest oil basin in Texas, the Permian Basin. We’re getting started on that, but it’s a complicated play.

We are also in conversation with the Ohio government to help them understand and perhaps consider a similar study in the Utica Play.

Between that, our team finishing the Marcellus, as well as doing a loop back into our other three basins, we’re pretty busy.

ST – In addition, we are expanding the study into new areas. With additional funding from the Sloan Foundation and the Mitchell Foundation we are looking into the water resources associated with shale gas and shale oil production. Until recently data on water use in hydraulic fracturing was very sparse. Because of new regulations, operators are now reporting how much water they use. Bridget Scanlon and JP Nicot from BEG are leading the way on that one.

COULD YOU DO MORE STUDIES IF YOU HAD MORE MONEY?

ST – It’s not just about resources. It’s about balancing and managing the bureau’s expertise. We could always expand it by hiring more people but the quality would deteriorate. Whatever research we produce needs to be of the highest quality. That’s what’s important to us.

Back to the Newsletter