Field Geology in Virtual Reality

December 5, 2022

BY JULI BERWALD

When asked why he has spent the past 35 years studying outcrops, Jackson School of Geosciences Professor Charles Kerans, who also co-founded the Bureau of Economic Geology’s Reservoir Characterization Research Laboratory (RCRL), said “outcrops are a mental image of what things ought to look like.”

CARBONATE RAMP.

It’s the word “image” that has been a main driver behind a new initiative at RCRL: to image a suite of informative outcrops in three dimensions. The detailed images will be interwoven with critical geological information and comments from experts such as Kerans, creating the virtual experience of taking a field trip to see “what things ought to look like,” all while sitting at your desk. Although still in its early stages, this virtual reality project has vast potential for both education and industry.

Outcrops have proved valuable to geologists because the methods of studying the subsurface are limited by the available tools. Cores have very high resolution, but their scale is only 5 to 10 centimeters in diameter, which means piecing together structures from narrow windows of information. Seismic imagery can cover tens of square miles continuously, but the vertical resolution is commonly limited to 10 to 30 meters.

“In order to have a clear understanding of what the subsurface looks like,” Kerans said, “it’s extremely helpful to go see [outcrops to understand] what the rocks would actually look like in terms of scale and style of layering or other types of important patterns. We might study fracture distributions, or we might study distribution of corals on a reef, and that would be impossible to figure out from subsurface data.”

Studying outcrops has proved so important to oil and gas exploration that thousands of people, including members of RCRL’s industrial associates and students, have joined Kerans, Chris Zahm, Xavier Janson and other RCRL leaders on field trips to outcrops over the decades. Outcrops are also important for understanding the extent and behavior of aquifers, developing models of climate change and past sea level positions, and, as the world looks to shift to electric vehicles and battery storage, evaluating locations of critical metals such as lithium.

Yet, a major impediment is that opportunities to physically visit outcrops are not available to everyone all the time for a variety of reasons.

“There’s one outcrop that’s illustrative of the current exploration activity within the Permian Basin,” RCRL structural geologist Zahm said, referring to a place known as Apache Canyon in the Sierra Diablo mountains of West Texas. But the location was recently purchased by a private landowner. “So now we can’t see it.”

Many informative outcrops in Texas are, in fact, on private property, making access limited due to regulations.

Not only property rights, but physical capability can also impede the ability to view and study outcrops. Remote locations, rough terrain and steep inclines limit people’s ability to visit and understand important geological structures. Informative outcrops exist all over the world, from the Australian coastline to the Arctic Circle. Time to fly to those places and money to fund the trips are also significant barriers.

To address these obstacles, Kerans, Zahm, Janson, Robin Dommisse, and then-doctoral student Buddy Price (Ph.D., 2021) envisioned a virtual reality system that would allow anyone to explore outcrops “from a desk chair, right now,” Zahm said. Price developed a proof-of-concept model that began the current efforts.

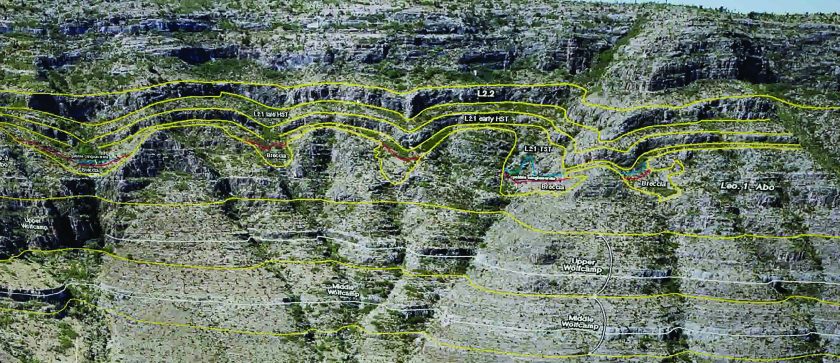

The project started in 2021 with highly detailed Lidar imagery collected by the U.S. Geological Survey at outcrops in Texas and New Mexico. Then, drones were flown back and forth across the outcrops, taking imagery at multiple angles. Using photogrammetry — the same technology used to combine images in View-Master stereoscopes — the images were stitched together into three- dimensional models.

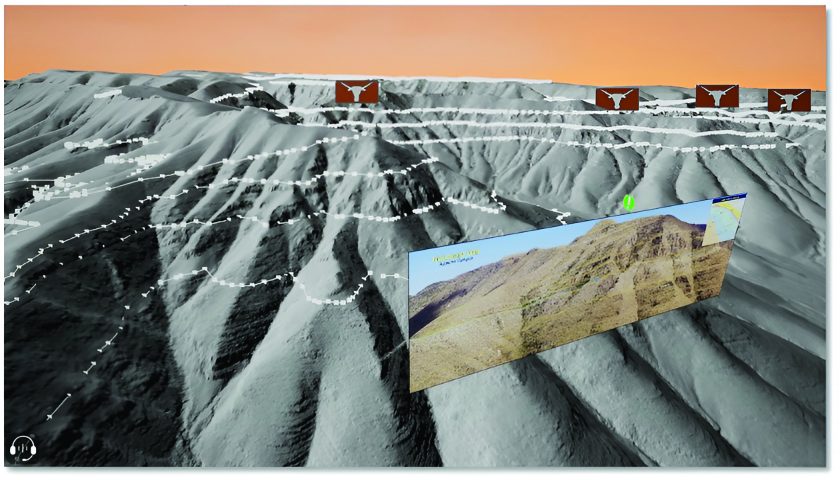

Although the technology is still in a beta version, a user will experience the virtual outcrop from a first-person point of view, initially through a web browser, so no software will need to be downloaded. Eventually, Zahm said, the project will be ported to an immersive experience with VR goggles and headset.

Layered on top of the 3D drone imagery, the researchers can “paint in” geologically relevant structures. And at the same time, they capture video of experts such as Kerans describing experience, gigabytes of data and huge amounts of computer time are involved.

To wrestle the concept into code, Janson and Zahm began collaborating with The University of Texas at Austin Department of Computer Science.

The project now uses a commercial visualization program called Unreal Engine, which is software developed for the kinds of three-dimensional environments used by wildly popular computer games such as Fortnite and highly visual television shows such as “The Mandalorian.”

Although the software is still in development, a virtual field trip of an outcrop called Dog Canyon in the Sacramento Mountains of New Mexico starts with a view of the entire 2,500-foot-tall structure. A user can turn the entire outcrop in three dimensions like spinning a rock in your hands. This outcrop contains dauntingly steep cliffs.

As the user moves the virtual outcrop rightward, Charlie Kerans comes into view. He is discussing the clastic and carbonate layers. As Kerans refers to various cross sections, they appear as floating slide projections.

Zahm said that it’s not just about providing a virtual world, “it’s about adding critical information.”

Kerans points out that once a catalog of VR outcrops has been assembled, their usefulness will extend well beyond the virtual field trip model that’s currently in development.

“In a VR world, you could stack together two or three different examples that you really want to compare but would be impossible to do in the short term,” Kerans said. “You could compare the formations during field trips. These videos are laced into the imagery like waypoints that can be clicked on as various locations in the virtual world.

“We want you to be interactive in the environment,” Zahm said. “So there’s a floating symbol that says, ‘Hey, there’s information to talk about [here], and now I can just walk over the surface to that spot.’”

Depending on the purpose, those waypoints could be very specific reservoir characteristics relevant to petroleum engineers, good fossil-hunting spots for a general audience, or points of interest for National Park visitors.

But with outcrops that can soar up to 3,000 feet of local relief or more and stretch for tens of miles, the amount

of data required for a seamless virtual reality outcrop quickly becomes massive. To shift perspective — or in virtual reality parlance, level of detail — from the kilometer scale to the meter scale to the centimeter scale with the kind of smoothness that feels like human the Canning Basin of Australia, and the Cretaceous of central Mexico, and the Permian in the Guadalupe Mountains [of Texas]. You could start to see what different ancient reefs looked like and the associated deposits in a way that you really can’t do otherwise.”

Although outcrops in virtual reality are still in early stages of development at RCRL, their potential is clearly immense.

“I think that as we do more of this,” Kerans said, “you’re only limited by your own imagination.”

Back to the Newsletter