Life Finds a Way at Impact Site of Dino-Killing Asteroid

December 3, 2018

About 66 million years ago, an asteroid smashed into Earth and triggered a mass extinction that ended the reign of the dinosaurs and snuffed out 75 percent of life.

While the impact killed off species across Earth, researchers from The University of Texas at Austin have found that the crater itself served as a habitat for sea life mere years after impact and was a thriving ecosystem within 30,000 years — a much quicker recovery than other sites around the globe.

Scientists were surprised by the findings, which undermine a theory that recovery at sites closest to the crater is the slowest due to environmental contaminants — such as toxic metals — released by the impact. Instead, the evidence suggests that recovery around the world was influenced primarily by local factors.

“We found life in the crater within a few years of impact, which is really fast, surprisingly fast,” said Chris\ Lowery a research associate at the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics (UTIG) who led the work as a UTIG postdoctoral researcher. “It shows that there’s not a lot of predictability of recovery in general.”

The research was published May 30, 2018, in the journal Nature. UTIG research scientists Gail Christeson

and Sean Gulick and postdoctoral researcher Cornelia Rasmussen are coauthors on the paper, along with a team of international scientists.

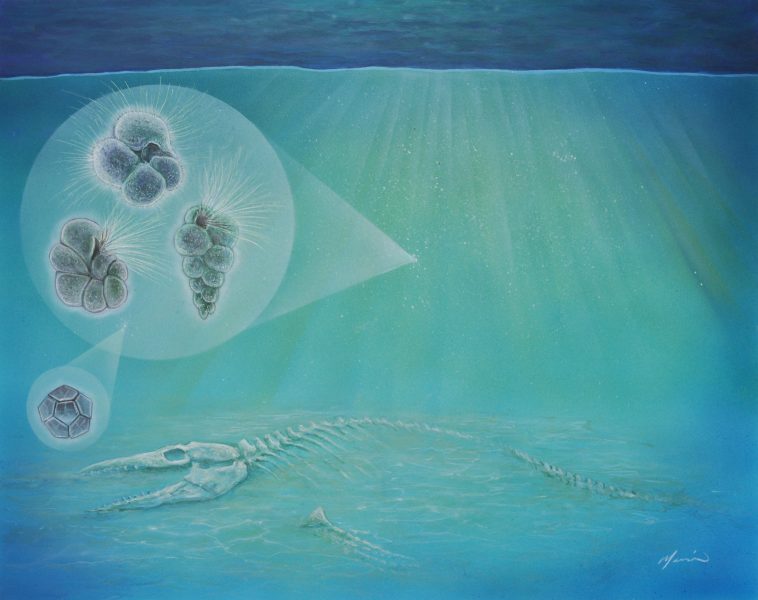

The evidence for life comes primarily from the remains of unicellular organisms such as algae and plankton

— as well as the burrows of larger organisms discovered in rock extracted from the crater during recent scientific drilling mission.

The scientists found the first evidence for the appearance of life two to three years after impact. The evidence included burrows made by small shrimp or worms. By 30,000 years after impact, a thriving ecosystem was present in the crater, with blooming phytoplankton (microscopic plants) supporting a diverse community of organisms in the surface waters and on the seafloor. In contrast, other areas around the world, including the North Atlantic and other areas of the Gulf of Mexico, took up to 300,000 years to recover in a similar manner.

The core containing the fossil evidence was extracted from the crater during a 2016 expedition co-led by the

Jackson School of Geosciences. In this study, scientists zeroed in on a unique core section that provides a record of the seafloor environment days to years after the impact.

The relatively rapid rebound of life in the crater suggests that the impact didn’t hamper recovery. The scientists point to local factors, from water circulation to interactions between organisms and the availability of ecological niches, as having the most influence on a particular ecosystem’s recovery rate.

The research was funded by the International Ocean Discovery Program, the International Continental Drilling Program, the National Science Foundation and NASA.

Back to the Newsletter