Mapping Texas Then and Now

October 14, 2016

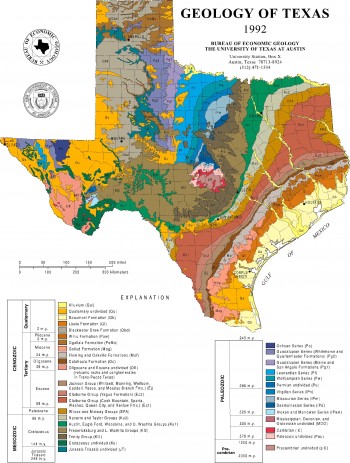

From its humble origins as little more than a visual guide to surface rock formations, the geologic map has evolved into a rich, multilayered tool used by a variety of disciplines. In Texas, the Jackson School of Geosciences Bureau of Economic Geology has been central to that evolution for over a century.

From its humble origins as little more than a visual guide to surface rock formations, the geologic map has evolved into a rich, multilayered tool used by a variety of disciplines. In Texas, the Jackson School of Geosciences Bureau of Economic Geology has been central to that evolution for over a century.

By John Holden

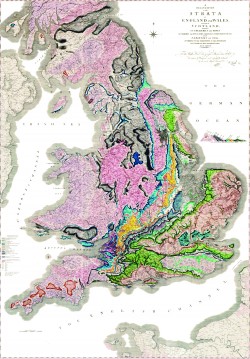

When William Smith presented the very first geologic map of Britain to the world 200 years ago, both the creator and his pioneering masterpiece were ignored by the British scientific establishment of the time.

Recognition for the “Father of English Geology” eventually came later in life, but not before his map had been widely plagiarized, and he had endured several years of financial hardship.

While Smith may not have initially received the credit he deserved, he would likely take comfort knowing just how far things have come since his map was published in 1815. By the 20th century, his revolutionary approach to mapping—showing three-dimensional representations of geologic strata on a two-dimensional map—had been adopted by aspiring geologists worldwide, including those mapping the landscape in Texas.

Geologic mapping has been one of the principle duties at the Bureau of Economic Geology since its establishment in 1909. As the state geological survey, the bureau has been officially responsible for mapping the Lone Star landscape for more than a century.

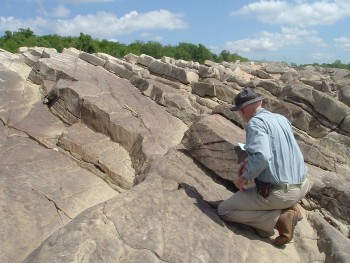

“Back then geologists would have gone out on foot or horseback and simply recorded the surface rocks they saw on a given plot of land,” said Edward Collins, bureau research scientist associate and resident geologic mapping expert. In its early days much of the bureau’s research was tied up in exploration for minerals deemed economically valuable—hence the “economic” part of the bureau’s moniker.

“In those days, geologic mapping was commissioned by those in search of natural resources such as coal, copper and building materials like limestone,” Collins explained. Fast forward 100 years and the functions and applications of the geologic maps being produced have grown to include data prized in a variety of scientific disciplines.

“Given our dual role as the state geological survey as well as an independent multidisciplinary research institute, it’s no surprise that geologic mapping at the bureau has extended beyond the original recording of geographical rock formations,” said Michael Young, bureau associate director for environmental systems and senior research scientist. “While every state survey has its own mapping program, few, if any, have as wide a reach as ours here at The University of Texas.” The geologic map of the 21st century is first and foremost a visual illustration of the distribution of geologic features, but it has a myriad of other applications depending on who is using it.

In Texas, applications vary depending on location. In the Central Plains, maps are informing planning and management of land. In coastal environments, they’re helping to monitor change in coastal depositional environments, respond to erosion and assess the suitability of resource development activities, including managing future plans for development of energy and industrial mineral resources, and commercial and

recreational interests.

In this context, map applications are often critical to supporting the continued growth of the Texas economy. But geologic mapping in Texas is not motivated purely by commercial imperatives.

Ongoing projects developed as part of the combined state and federal STATEMAP Program are used to monitor natural depositional and erosion processes as well as human activities known to impact water quality. This includes making geologic maps of the Texas Gulf Coast Corridor. In addition, boundaries of wetland environments, shoreline changes and the littoral sediment budget can also be assessed. Equipped with this kind of information, maps can be used to help resource management decisions, support coastal research and inform conservation projects that protect threatened wetland environments.

How the geologic map has evolved from paper format to the multilayered tool it is today—used by engineers, realtors, surveyors, scientists, city planners, conservationists, tourists and others—relates in no small part to recent technological advances.

“Almost everything is now done on computers,” Collins said. “Field research is still required, but these days, students and researchers bring tablets with GPS capability, and other mapping-related programs.”

In particular, the modern geologic map owes much of its sophistication to advances in aerial photography and satellite imagery technology. Lidar—a laser-based light system used to determine topography—has been enthusiastically adopted by the geologic mapping community at the bureau.

“The high resolution measurements and accuracy of the topography become the foundation for many other geologic features,” Young said.

“We can then map rock types, geological features, vegetation, on top of the topography, helping us identify relationships that before were more difficult to see.”

Geologic mapping at the bureau has even extended to include measuring temperature variations within river systems in order to understand where ideal habitat conditions favorable to fish and other species are likely to be found.

This kind of research is but one example demonstrating how geologic mapping plays a central role in conservation efforts. There’s no telling what other novel uses might be found for the geologic map of the future. Yet the map itself will always retain core features that have been a constant since the days of Smith.

“The applications may have widened, but the basic functions have not,” Young said. “Each standard map will still have the same geologic illustrations detailing sediment or rock units at the surface, but now there’s all this additional metadata that’s available.”

ON THE GROUND: GEOLOGIC MAPPING IN ACTION

Ecosystem Mapping at Powderhorn Ranch

In 2014, history was made when $37.7 million was raised for the purchase of the

17,351-acre Powderhorn Ranch in Calhoun County, the largest amount ever paid for a

conservation land purchase in the state’s history.

Located on the Gulf Coast, the ranch is one of the biggest tracts of unspoiled coastal

prairie land left in Texas and was paid for through a partnership between the Texas

Parks and Wildlife Foundation, The Nature Conservancy and The Conservation Fund. It

will eventually become a state park and wildlife management area managed by the Texas

Parks and Wildlife Department.

After making the substantial investment, the state turned to the bureau to map the

property and produce a print and digital geoenvironmental atlas of the management area

to assist planners, managers and conservationists.

Through initiatives funded by the Texas General Land Office and the U.S. Geological

Survey, bureau researchers are studying ecosystems that include bay frontage, tallgrass

prairie, fresh and saltwater wetlands, as well as live oak woodlands established on the

Ingleside barrier-strandplain, an ancient barrier system formed along the Texas coast

during the last Pleistocene interglacial period about 100,000 years ago.

Projects include an airborne lidar survey to create a high-resolution topographic model

of the area and an aerial hyperspectral survey to help determine habitat distribution.

“We’re also taking ground and borehole geophysical measurements and acquiring soil

samples to determine paleoenvironments and ages of the shallow strata,” said Jeffrey

Paine, senior research scientist at the bureau.

RURAL & URBAN MAPPING

Powderhorn Ranch is not the bureau’s only project on the coast.

“It ties into what we’re doing across the Middle Texas Gulf of

Mexico Coastal Plain,” said Edward Collins, a research scientist

associate at the bureau.

Another one of those projects is mapping in environmentally

sensitive areas adjacent to Matagorda and Lavaca bays.

New maps of these areas will help assess coastal erosion and

permit activities related to resource development, Collins said.

They’ll also assist in evaluating historical changes of coastal

depositional environments.

Away from the coastal wetlands and near the state’s capitol,

the bureau is assisting with urban development plans by

creating geologic maps of areas west of Austin within the

Central Texas transportation/population corridor, areas that

have experienced major population increases and significant

suburban development in recent years.

Geologic maps are being produced to help address needs

for planning and managing groundwater, surface water, land

use and construction projects. So far, researchers have been

busy mapping in the upper Lake Travis area as far south as

Wimberley, including Mansfield Dam and Dripping Springs.

However, this project is far from complete, and plans are in

place to chart regions further west in the coming years.

MAPPING THE THREATENED

Outside of Texas, bureau researchers are creating

geological maps to help save a desert tortoise in Nevada.

Using lidar and imaging technologies, researchers

are assessing potential habitats in Eldorado Valley, south

of Las Vegas, Nevada, for Gopherus agassizii, a threatened

species of desert tortoise found in the Southwest.

The assessments include measuring vegetation, diversity

in plant canopies and landscape characteristics.

This is not the only project where the bureau has used

its mapping expertise to assist in species conservation. In

the recent past, the bureau has undertook studies in Texas,

including mapping habitats for the endangered earless

lizard, the western chicken turtle and the fresh-water

mussels found in several Texas rivers.

Michael Young, a senior research scientist and associate

director for environmental systems at the bureau, said

that techniques being used in Nevada could help in future

Texas conservation projects.

“The technique we’re attempting to use—which is

a combination of remote sensing and on-the-ground

mapping—could be very helpful in Texas, particularly on

our military bases where many are also dealing with the

conservation of species on the threatened or endangered

list,” Young said.