Former Graduate Student Redraws Family Tree of Extinct Crocodile-like Animals

November 8, 2013

Michelle Stocker (PhD ’13), former graduate student in The University of Texas at Austin’s Jackson School of Geosciences, has dramatically rearranged the evolutionary tree for several extinct crocodile-like animals that lived over 200 million years ago in present day Texas, Wyoming and Germany. Based on this new understanding, she has renamed one of the specimens Wannia scurriensis in honor of the paleontologist who first described it in 1949, Wann Langston, Jr. Langston was an internationally renowned professor at the university who died this past spring.

Since the first of these crocodile-like specimens was described in 1904, they were sometimes assigned to one species and sometimes to three or four distinct species, yet always within a single genus called Paleorhinus. According to Stocker’s new analysis, the Paleorhinus specimens represent at least four distinct species in three genera. This work, which appears in a special volume honoring Wann Langston published online in several installments in September and October 2013 in the journal Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, has important implications for dating several fossil sites.

“Specimens from a wide geographic range and potentially a wide time range were all lumped into the same group,” says Stocker. “That means those sites were all thought to be about the same age. But now we see they might not be.”

Stocker said this work demonstrates the importance of preserving and maintaining fossil collections. Even when a specimen like Wannia scurriensis has been carefully analyzed and described in the scientific literature, new technologies, methodologies and comparative specimens allow scientists to continue to glean new insights.

“It’s a historic specimen—Langston described it back in 1949,” says Stocker. “And we’re still finding out new things about it today.”

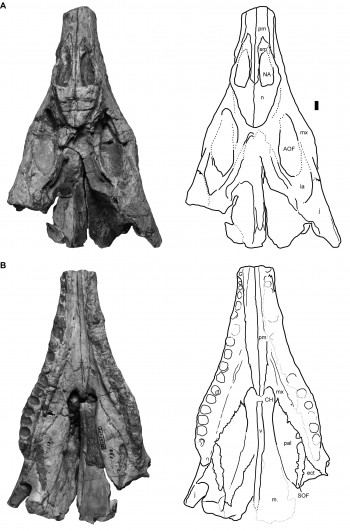

Stocker used a technique called cladistics to test the evolutionary relationships of the various specimens that had been assigned to Paleorhinus and how they fit into the larger group of reptiles to which they belong, called phytosaurs. Following this technique, she searched for shared, derived physical traits of the specimens—such as the presence of a ridge on the back of the skull or the relative positions of the nostrils—which were not present in distantly-related groups or in phytosaurs known from later times. By applying a few simple rules about how certain characteristics evolve over time, she generated the new set of relationships.

Stocker’s hypothesis of relationships is different from earlier ones because many of the traits originally used to diagnose the genus Paleorhinus turned out to be traits that those specimens shared ancestrally with all known phytosaurs. Because they were shared with all other phytosaurs, those characters were uninformative for more specific relationships among the specimens that had been included in Paleorhinus previously. In this paper, and another new manuscript that Stocker is working on with several European colleagues, derived features specific to Paleorhinus are outlined in detail and tested.

Stocker’s paper is one of many included in the special volume honoring Dr. Langston that have to do with historic specimens which he described or worked on during his career as a vertebrate paleontologist. Included in that volume are empirical and conceptual papers about a broad range of fossil vertebrates, ranging from the Permian through the Quaternary. Some of those papers were presented in a special symposium at the South-Central Section meeting of the Geological Society of America held in Austin in April 2013.

by Marc Airhart

View the paper “A new taxonomic arrangement for Paleorhinus scurriensis” at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1755691013000340

To access the special volume go to: http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayIssue?jid=TRE&volumeId=103&seriesId=0&issueId=3-4