New Meat-Eating Dinosaur Alters Evolutionary Tree

December 10, 2009

Paleontologists, aided by amateur volunteers, have unearthed a previously unknown meat-eating dinosaur from a fossil bone bed in northern New Mexico, settling a debate about early dinosaur evolution, revealing a period of explosive diversification and hinting at how dinosaurs spread across the supercontinent Pangaea.

A live embargoed webcast with the scientists will be held in advance of publication for credentialed reporters on Dec. 9. See details below.

The description of the new species, named Tawa after the Hopi word for the Puebloan sun god, appears in the Dec. 10 issue of the journal Science in a paper lead-authored by Sterling Nesbitt, a postdoctoral researcher at The University of Texas at Austin’s Jackson School of Geosciences. Nesbitt conducted the research with his colleagues while a graduate student at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory and the American Museum of Natural History.

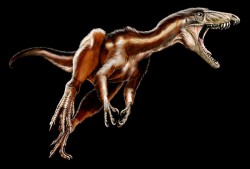

The fossil bones of several individuals were recovered, but the type specimen is a nearly

complete skeleton of a juvenile that stood about 28 inches (70 cm) tall at the hips and was about 6 feet (2 meters) long from snout to tail. Its body was about the size of a large dog, but with a much longer tail. It lived about 214 million years ago, plus or minus a million. The specimens are remarkable because they show little sign of being flattened during fossilization.

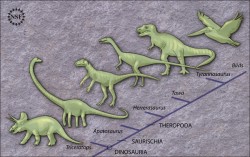

Tawa is part of a group of dinosaurs known as theropods, which includes T. Rex and Velociraptor. Theropods for the most part ate meat, walked on two legs and had feathers. Though most went extinct by 65 million years ago, some lineages survived to spawn modern birds.

One of Tawa’s most important contributions to science has to do with what it says about another dinosaur, Herrerasaurus, the center of a lively debate since its discovery in Argentina in the 1960s. Herrerasaurus had some traits in common with theropods—including large claws, carnivorous teeth and certain pelvic features—but lacked other theropod traits such as pockets in vertebrae for airsacs. Some paleontologists claimed it was so unusual it was outside the evolutionary tree of theropods, or even of dinosaurs. Others placed it among the earliest theropods.

“The question was did those carnivorous traits arise in Herrerasaurus and in theropods independently or were they traits from a recent common ancestor that got passed down,” said Nesbitt. “We had so few specimens of early theropods that it was hard to answer that question. But now that we have Tawa, we think we have an answer.”

Tawa had a mix of Herrerasaurus-like characteristics (for example, in the pelvis) and features found in firmly established theropod dinosaurs (for example, pockets for airsacs in the backbone). Therefore, the characteristics that Herrerasaurus shares uniquely with theropods such as Tawa confirm the characteristics didn’t arise independently and that Herrerasaurus is indeed a theropod.

The firm placement of Herrerasaurus within the theropod lineage points up an interesting fact about dinosaur evolution: once they appeared, they very rapidly diversified into the three main dinosaur lineages that persisted for more than 170 million years. Herrerasaurus was found in a South American rock layer alongside the oldest members of two major lineages—the sauropods and the ornithischians.

“Tawa pulls Herrerasaurus into the theropod lineage, so that means all three lineages are present in South America pretty much as soon as dinosaurs evolved,” said Nesbitt. “Without Tawa, you can guess at that, but Tawa helps shore up that argument.”

Tawa skeletons were found beside two other theropod dinosaurs from around the same period. Nesbitt noted that each of the three is more closely related to a known dinosaur from South America than they are to each other. This suggests these three species each descended from a separate lineage in South America, rather than all evolving from a local ancestor, and then later dispersed to North America and other parts of the supercontinent Pangaea. It also suggests there were multiple dispersals out of South America.

The first Tawa fossils were discovered in 2004 by volunteers taking a week-long paleontology seminar with experts at the Ruth Hall Museum of Paleontology in Abiquiu, New Mexico. The dig site, known as Hayden Quarry, is in a hillside on Ghost Ranch made famous by the painter Georgia O’Keefe. Alex Downs, an instructor for the course, contacted Nesbitt and a colleague to ask if they’d like to take a look at the fossils. There was a thigh bone, part of a hip and what later turned out to be some unrelated vertebrae.

“When we saw them, our jaws dropped,” said Nesbitt. “A lot of these theropods have really hollow bones, so when they get preserved, they get really crunched. But these were in almost perfect condition.”

He was also surprised by how much material was preserved at this one site. He and his colleagues began a full-scale excavation in 2006. Every summer since then, they’ve continued to unearth new material. The fossil bone bed extends for tens of meters along the hillside, promising years of painstaking work and perhaps additional significant discoveries.

Nesbitt’s co-authors included Nathan Smith of the University of Chicago and the Field Museum of Natural History, Randall Irmis of the Utah Museum of Natural History and the University of Utah, Alan Turner of Stony Brook University, Alex Downs of the Ruth Hall Museum of Paleontology in Abiquiu, New Mexico, and Mark Norell of the American Museum of Natural History.

The National Science Foundation and the National Geographic Society sponsored the research, which was featured in the NSF-funded IMAX 3-D movie “Dinosaurs Alive!”.

For more information about research at the Jackson School, contact J.B. Bird at jbird@jsg.utexas.edu, 512-232-9623.