Exploring Europa

November 2, 2015

Jackson School scientists play a key role in NASA’s quest to find life-supporting environments on Jupiter’s moon

By Monica Kortsha and Anton Caputo

Jupiter’s moon Europa is a frozen world covered completely in a thick layer of ice.

The icy coating makes Europa the smoothest surface in the solar system, as well as one of the brightest. Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei was able to first spot the moon using only a simple telescope in 1610. Another Galileo, the NASA spacecraft, improved the view in the late 1990s by revealing a landscape of crisscrossed ice cracks and ridges.

But the most unique feature of the moon may lie beneath its frozen exterior: a liquid ocean capable of supporting life.

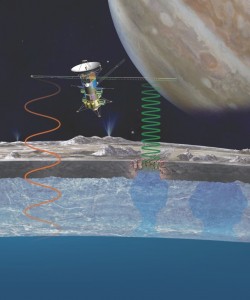

NASA is planning to send a spacecraft in the 2020s to scan Europa for signs of water beneath the ice, as well as chemical ingredients needed for life. Announced in the summer of 2015, among the nine instruments onboard the craft will be an ice-penetrating radar developed by the Jackson School of Geosciences Institute for Geophysics (UTIG).

Called REASON (Radar for Europa Assessment and Sounding: Ocean to Near-surface), the radar will allow scientists, for the first time, to peer beneath Europa’s smooth shield of ice.

Its development will be overseen by principal investigator Donald Blankenship of UTIG. He and his Texas team are also collaborating with the European Space Agency and Italian Space Agency on their plans for a radar instrument focused on Jupiter’s moon Ganymede, the largest moon in the solar system. Since the 1990s, Blankenship has been using a similar ice-penetrating radar system carried by plane to study the substructure of the ice sheets of Antarctica and Greenland.

On Europa, the NASA radar will be searching for pockets of water within the ice shell that could serve as passageways to the ocean below for surface-based sulfuric compounds, a chemical building block for life. Under the ice, an environment where life could develop may exist.

“Europa is cold, but it’s not totally unimaginably cold,” said Blankenship. “The bottom of that ice shell has the same temperature, the same pressure and possibly the same salinity as the bottom of the ice floating at the grounding lines of Antarctica.”

In other words, “It’s Earth,” Blankenship said.

A sign supporting the presence of passageways through the ice is Europa’s “chaos” terrain, areas on the surface that resemble toppled icebergs jutting out from the ice. The terrain is thought to be formed by buoyant upwellings of warm ice, called “diapirs,” rising from the bottom of the ice toward the surface. As a diapir rises, it melts the surface of the ice, collapsing it and enabling chemicals at the surface to mix with the water from below.

On Earth, portions of floating ice shelves that collapse form similar structures.

The chaos terrain was first observed on Europa by NASA’s Galileo spacecraft nearly 20 years ago. Blankenship’s radar should confirm whether the terrain marks the locations of passageways to an ocean.

Blankenship has been using radio waves emitted by radar systems to capture the environment beneath Earth’s great ice sheets in Antarctica and Greenland for the past 30 years. The REASON system will work the same way. But to ensure effective penetration of Europa’s ice, the radar will rely on two frequencies: a longer 9 MHz wave and shorter 60 MHz wave.

The longer wave can easily pass through Europa’s ice before being reflected back to the receiver. However, radio waves emitted by the planet Jupiter interfere with the signal, so it can only be used on the side of Europa facing away from the planet. In contrast, the shorter waves can scan the entire surface because they are unaffected by Jupiter. But they are more susceptible to interference from rough patches of Europa’s ice.

“By using two frequencies, the radar can present a more comprehensive and clear image of Europa’s ice shell,” Blankenship said.

The radar for the NASA mission will be installed on the space craft in a manner similar to the way it’s attached to the DC-3 aircraft used by UTIG to study Earth’s ice sheets, with radio antennas separated from one another by slightly more than 50 feet. UTIG will oversee the development of the REASON system, with construction being handled by engineers at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the University of Iowa.

Blankenship has also organized a 20-person science team to advise on the radar’s construction, and its data acquisition and analysis. This team includes scientists from UTIG, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, Washington University in St. Louis, the Smithsonian Institution, Arizona State University, the University of Iowa, the University of California Santa Cruz, NASA’s Ames Research Center, the Planetary Science Institute, Georgia Tech and NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, as well as German, French and Italian institutions.

In 2011, UTIG scientists were among those that found evidence of water being trapped beneath the moon’s icy exterior. Studying Europa is not new for UTIG. And in 2013, Blankenship, Krista Soderlund and other UTIG scientists helped develop the blueprint for a possible future NASA lander mission to Europa.

It will be a decade or more before the spacecraft reaches Europa. Because of the long-term nature of the work the team has paired senior scientists with early career ones to ensure a continuity of knowledge throughout the duration of the mission.

“It’s a lifetime-scale process,” said Duncan Young, a UTIG Antarctic researcher and team member. Soderlund, an expert on planetary oceanography, and Cyril Grima, a planetary radar expert, are other UTIG researchers on the science team.

The REASON system will scan for water under the ice, and also search for signs of it out in space and on Europa’s surface. The Galileo probe has found evidence of Europa releasing water as giant, geyser-like plumes that reach into space and then fall back to the surface as snow. If mixing has occurred between surface compounds and water below, signs of the compounds are expected to be present in the plumes or snow.

If the radar detects water and a way for it to mix with material at the surface, it could help jumpstart new research endeavors, such as a future lander mission to Europa’s surface and ocean. If life was ever found on Europa, it would indicate that it exists across the universe, said Young.

“If you go to this completely different environment, one that has all the chemistry to support life, and it actually turns out to have life, in the end you’ve got two examples in one solar system of life emerging,” Young said. “It would imply that all those exoplanets that they’re finding out there may have something on them as well.”

Back to the Newsletter