Drying Out

October 22, 2014

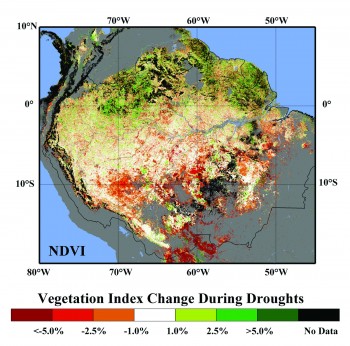

A new study suggests the southern portion of the Amazon rainforest is at much higher risk of dieback due to stronger seasonal drying than projections reported by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

If severe enough, the loss of rainforest could cause the release of large volumes of the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. It could also disrupt plant and animal communities in one of the most biodiverse regions of the world.

Using ground-based rainfall measurements from the past three decades, a research team led by Rong Fu, professor at the University of Texas at Austin’s Jackson School of Geosciences, found that since 1979, the dry season in southern Amazonia has lasted about a week longer per decade. At the same time, the annual fire season has become longer. Researchers say the most likely explanation for the lengthening dry season is global warming.

“The length of the dry season in the southern Amazon is the most important climate condition controlling the rainforest,” said Fu. “If the dry season is too long, the rainforest will not survive.”

The findings were reported in the Nov. 5, 2013, issue of the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Researchers say the most likely explanation for the lengthening dry season is human-caused greenhouse warming, which inhibits rainfall in two ways. First, it makes it harder for warm, dry air near the surface to rise and freely mix with cool, moist air above. Second, it blocks cold front incursions from outside the tropics that could trigger rainfall. The climate models used by the IPCC poorly represent these processes, possibly explaining its projection of only a slightly longer Amazonian dry season, said Fu.

The Amazon rainforest normally removes carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, but during a severe drought in 2005, it released 1 petagram of carbon (about one-tenth of annual human emissions) into the atmosphere. Fu and her colleagues estimate that if dry seasons continue to lengthen at just half the rate of recent decades, the 2005 drought could become the norm rather than the exception by the end of this century.

“Because of the potential impact on the global carbon cycle, we need to better understand the changes of the dry season over southern Amazonia,” said Fu.

Back to the Newsletter