Fault Healing

December 12, 2023

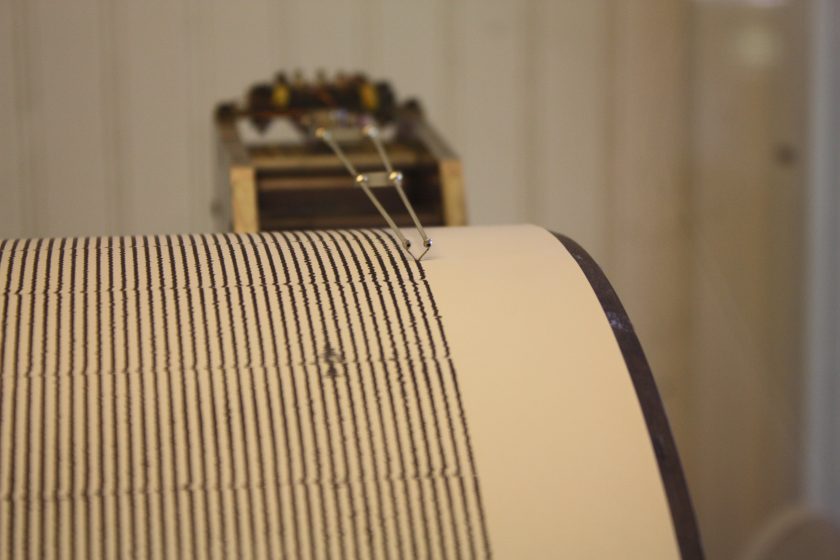

Scientists at the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics (UTIG) have found that slow-healing faults are more likely to move harmlessly, while those that heal quickly are more likely to stick until they break in a large, damaging earthquake.

The discovery could be key to understanding when, and how violently, faults move. That alone won’t allow scientists to predict when the next big one will strike — the forces behind large earthquakes are too complex — but it does help researchers investigate the potential for large, damaging earthquakes in different places.

“The same physics and logic should apply to all different kinds of faults around the world,” said the study’s co-lead author and UTIG Director, Demian Saffer. “With the right samples and field observations, we can now start to make testable predictions about how big and how often large seismic slip events might occur on other major faults, like Cascadia in the Pacific Northwest.”

The results were published in the journal Science.

To make the discovery, researchers devised a test that combined rocks from a well-studied fault off the coast of New Zealand and a computer model to successfully calculate that a harmless kind of “slow motion” earthquake would happen every few years. The results were nearly an exact match with observations from the New Zealand fault.

The researchers think the clay-rich rocks within the fault, which are very slow to heal, could be regulating earthquakes by allowing plates to slip quietly past each other, which limits the buildup of stress.

“This doesn’t get us any closer to actually predicting earthquakes, but it does tell us whether a fault is likely to slip silently with no earthquakes, or have large ground-shaking earthquakes,” said study co-lead author Srisharan Shreedharan, an affiliate researcher at UTIG and assistant professor at Utah State University.

The research was funded by UTIG, the International Ocean Discovery Program, and New Zealand’s GNS Science.

Back to the Newsletter