Dragon Defense

November 13, 2019

Just beneath their scales, Komodo dragons wear a suit of armor made of tiny bones. These bones cover the dragons from head to tail, creating a “chain mail” that protects the giant predators. However, the armor raises a question: What does the world’s largest lizard — the dominant predator in its natural habitat — need protection from?

After scanning Komodo dragon specimens with high-powered X-rays, researchers at The University of Texas at Austin think they have an answer: other Komodo dragons.

Jessica Maisano, a scientist at the Jackson School of Geosciences, led the research, which was published on Sept. 10, 2019, in the journal The Anatomical Record. The study’s coauthors are Christopher Bell, a professor in the Jackson School’s Department of Geological Sciences; Travis Laduc, an assistant professor in the UT College of Natural Sciences; and Diane Barber, a curator at the Fort Worth Zoo.

The scientists came to their conclusion by using computed tomography (CT) technology to look inside and digitally reconstruct the skeletons of two deceased dragon specimens — one adult and one baby. The adult was well-equipped with armor, but armor was completely absent in the baby. It’s a finding that suggests that the bony plates do not appear until adulthood. And the only thing adult dragons need protection from is other dragons.

“Young Komodo dragons spend quite a bit of time in trees, and when they’re large enough to come out of the trees, that’s when they start getting in arguments with members of their own species,” said Bell, a reptile expert. “That would be a time when extra armor would help.”

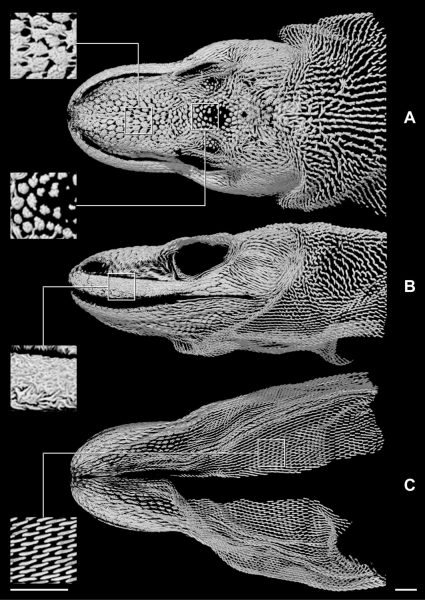

Many groups of lizards have bones embedded in their skin called osteoderms. Due to their tricky placement, scientists do not have much information about how the bony plates are shaped or arranged inside the skin. The researchers were able to overcome this issue by examining the dragons at the University of Texas High-Resolution X-ray Computed Tomography Facility, which is managed by Maisano. Due to size constraints of the scanner, the researchers scanned only the head of the nearly 9-foot-long, adult Komodo dragon.

The CT scans revealed that the osteoderms in the adult Komodo dragon were unique among lizards in both their diversity of shapes and sheer coverage.

“We were really blown away when we saw it,” Maisano said. “Most monitor lizards just have these vermiform (worm-shaped) osteoderms, but this guy has four very distinct morphologies, which is very unusual across lizards.”

The adult dragon that the researchers examined was among the oldest known Komodo dragons living in captivity when it died. Maisano said that the advanced age may partially explain its extreme armor; as lizards age, their bones may continue to ossify, adding more and more layers of material, until death. She said that more research on Komodo dragons of different ages can help reveal how their armor develops over time — and may help pinpoint when Komodos first start to prepare for battle with other dragons.

The National Science Foundation funded the research.

Back to the Newsletter