Scientist Profile: Randy Marrett

November 20, 2017

Professor Randy Marrett, a structural geologist, retired this summer after 23 years of research and teaching in the Department of Geological Sciences.

By Monica Kortsha

Marrett was a world-class educator and researcher whose work primarily focused on rock fractures and how fluid flows through them. It’s a key concept in geology, but a difficult one that often ends up frustrating many who try to take on the challenge, said Bureau of Economic Geology Senior Research Scientist Stephen Laubach, a longtime collaborator of Marrett’s.

“The path to solving any of these basic problems is just fraught with so many basic impediments … it takes a certain stubbornness to stay in the fight,” Laubach said.

Research on fractures is so challenging in part because it’s difficult to study fracture systems that exist deep underground, and understand how fractures behave as the environment changes. Marrett’s most highly cited papers use thorough field observations, combined with conceptual and mathematical insights on fracture and fault behavior.

One of these papers, a 1991 publication that is one of the most highly cited papers published in the Journal of Structural Geology, found that when it came to brittle faults, most methods were underestimating the number of fractures present in a given area — a point of particular importance to oil and gas companies interested in mapping out paths where hydrocarbons could go.

While at the Jackson School, Marrett conducted much of his fieldwork in the Sierra Madre Oriental Mountains in Northern Mexico, and in the Central Andes of Argentina and Chile. He is fluent in multiple dialects of Spanish. His and his students’ research in Mexico ranged from regional structure of the Sierra Madre Oriental fold-thrust belt and timing of thrusting to structural studies of detachment folds and structure and stratigraphy within the evaporate decollement.

In the Andes, they studied the intracontinental deformation and magmatism responses to late Cenozoic South American plate motion reorganization. Marrett was always more interested in sharing fracture research with those who could apply it, than rushing to publish in journals, Laubach said. To that end, in the 1990s, he and Marrett and collaborators in the Department of Petroleum & Geosystems Engineering (PGE) founded the Fracture Research and Application Consortium (FRAC) — an academic and industry partnership dedicated to studying fracture questions of interest to both groups.

Laubach credits FRAC’s success in part to Marrett’s skill in explaining the science of fracture research to any audience. Marrett, Laubach and Jon Olson, the PGE department chair and FRAC collaborator, used to run a lecture series on fractures in reservoirs for the American Association of Petroleum Geologists.

Marrett consistently received high rankings for his presentations. New research ideas could come to Marrett in a flash of brilliance. Laubach recalls a flight to Mexico where he saw Marrett doodling on a napkin. The sketch outlined a new technique for quantifying how fractures were arranged in a particular area.

“The new technique sprung out of his head fully formed,” Laubach said. “He is probably the closest thing to a genius the Jackson School ever had.”

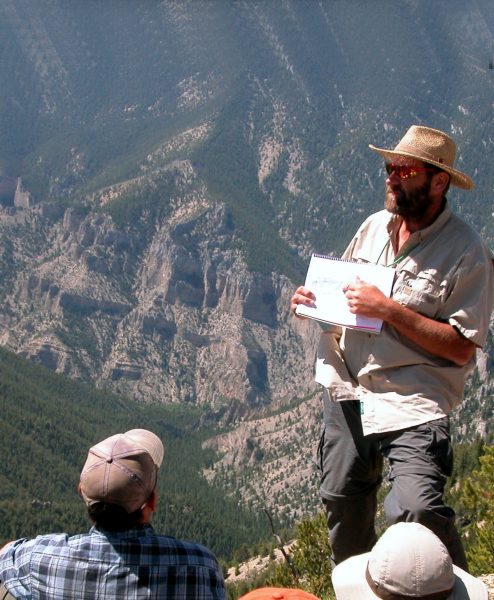

Marrett was an educator extraordinaire. Known widely for his teaching, he earned the ranking of “Awesome!” from the website Rate My Teachers. For many years, he taught GEO 428 Structural Geology and GEO 420K Stratigraphic and Field Methods courses, as well as Advanced Structural Geology and Brittle Structure for graduate students. His devotion to teaching was most evident in his yearly participation in GEO 660, an undergraduate field camp course. Marrett excelled at teaching in the field, both traditional fold-thrust belt mapping and interpretation and integration of thrust kinematics and dynamic processes during deformation.

Mark Helper, field camp director and longtime co-instructor with Marrett, was quick to point out his contributions.

“In 20-plus years of team teaching with dozens of faculty, Randy was simply the finest field instructor I’ve worked with,” Helper said. “He trained hundreds of undergraduates. His field skills are unparalleled and his creative teaching methods brought something new to our classes every year. Like the best teachers, he has the ability to explain complex ideas in simple terms and sketches. His contributions to our field program will be sorely missed.”

During his time at the university, Marrett supervised 20 M.S. and seven Ph.D. students and published 57 papers, which have been cited more than 3,608 times.

Elizabeth McKinnon, a master’s student of Marrett’s, said that he helped build confidence in her that all ideas are worthy of consideration.

“Randy is good at helping people think for themselves,” McKinnon said. “If you have 20 ideas and even if only two of them could be plausible, he still wants you to be able to come up with those 20 ideas and expand your mind, and think of all the possibilities.

Marrett was drawn to the field at an early age. A great lover of the outdoors and fishing, he moved to his cabin in Idaho when he retired and is now living off the grid. Far away from publications and people, McKinnon envisions Marrett spending the day going where his ideas lead him, with geology front and center.

“He takes things he’s heard, stories that don’t seem geology related, and he can always see why geology is the most important part of the story,” she said.

Back to the Newsletter