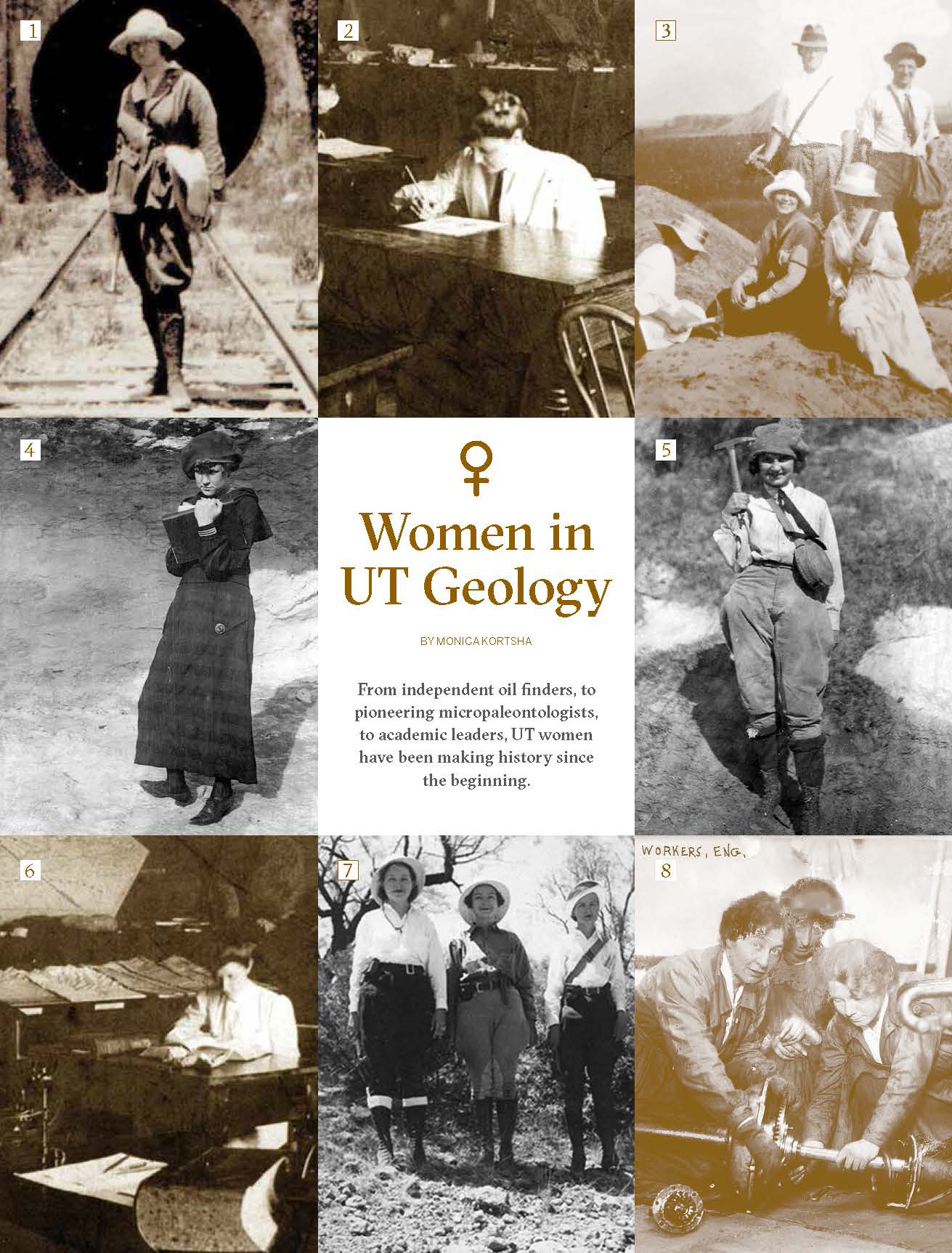

Women in UT Geology

November 20, 2017

By Monica Kortsha

In 1966, while on geology field camp at Colorado State University, Robbie Gries spotted a boulder as big as a house from the window of the class van as it moved through the White River Plateau.

“I think that’s granite over there!” Gries shouted to the other students—all men, save for the journalism-major wife of one of her classmates. Women were usually banned from the course, but Gries got in thanks to a mixture of the chairman being on sabbatical, other faculty being willing, and her offer to cook. She suspects her classmate’s wife came so she wouldn’t be the lone woman on the three-week course, and to help with the cooking.

Gries’ classmates disputed her granite claim: “You can’t have granite here! We’ve got Pennsylvanian-aged rocks on top, how would granite get on top of that? That’s such a dumb observation!”

But the professor turned the van around. The class ended up learning about glacial erratic boulders—large hunks of granite deposited by ice sheets as they carved the landscape during the last ice age. It wasn’t the last time Gries’ roadside observations made the professor do a U-turn.

“I loved field camp because I figured out that I really had an eye for geology in the field,” said Gries, who went on to earn her Master of Science in geology at The University of Texas at Austin, and serve as the first female president of the American Association of Petroleum

Geologists (AAPG).

“Many times on field trips I had experiences like that, and it gave me a lot of confidence.”

Gries’ story of overcoming gender barriers like the field-camp ban to find success in the geosciences is one of dozens compiled in “Anomalies: Pioneering Women in Petroleum Geology,” a new book about female AAPG members from the past 100 years. Gries wrote the book and released it at the 2017 AAPG annual meeting in Houston, along with a documentary, and a monumental 60-foot long poster featuring the first 100 female members of AAPG.

The roster starts in 1917, the year the AAPG was founded, and ends in 1945 — a date much earlier than Gries expected when she began the research in 2013.

“I was just amazed at how deep and rich [the history] was. I was amazed at how little I knew,” Gries said.

Women from UT played a notable role in AAPG’s early history — nearly 15 percent of the first 100 female members of AAPG either graduated or studied at some point at UT.

The Department of Geological Sciences also educated female

students who made important contributions outside of petroleum geology, and provided a space for mentorship, often from male members of the school who supported female students and researchers, and female student bonding.

At the same time, the school was also a reflection of larger cultural biases and expectations. Women were banned from going on undergraduate field camp until about the 1950s; the UT chapter of the geological honors society, Sigma Gamma Epsilon, excluded women for most of its existence; and a 1960s-era bulletin about the department for high school and college students could more easily

envision male geologists on other planets than women having a significant role in the field.

One paragraph reads: “A geologist’s activities may take him throughout the world. He may climb mountains, wade through swamps, descend into deep mines, brave the desert and attack jungles. … He may well be the first person to land on another planet.” Women are mentioned later in the passage: “A few women are engaged in geological work … Successful outdoor women field geologists are rare.”

Reading the biographies collected by Gries, combing through UT archives, and listening to the recollections of Jackson School alumnae and faculty, gives a nuanced view of the history of women in geosciences at UT and in geosciences research and industry over the past century. It’s far from a simple story.

The Start

The Department of Geology was founded in 1888 by Robert T. Hill, an orphan from Tennessee who earned his Bachelor of Science from Cornell University before coming to Texas at the invitation of the university regents.

In an inaugural address to the university’s faculty, he emphasized that the state benefits when both men and women receive an education based on technical, cutting-edge knowledge.

In accordance to Hill’s vision, women were part of these early geology classes. One such student was Harriet “Hattie” Whitten, who enrolled in the university in 1896. Although having no experience in geosciences, she convinced the school to allow her to take an introductory geology course because of a deep calling she had for the subject.

“From my ancestors I inherited a liking — no, I shall put it stronger, a love — for the studies of geology and geography in all of their different phases,” she wrote in a letter to her mentor Frederic Simonds, who replaced Hill as chairman of the department in 1890 and served as the department’s sole geology instructor for the next 10 years. “I begged to be granted the privilege of taking Geology I, as an extra, solely for the love of it.”

While enrolled in school, Whitten became Simonds’ assistant, earning a salary for her work. In 1899 she earned her Bachelor of Science, the first woman to do so from the department. That was followed a year later by her master’s degree — the first graduate degree bestowed by the department.

It’s likely that Simonds’ mentorship and encouragement factored into her decision to continue her studies. According to her obituary in the 1959 edition of the Newsletter, Whitten taught for one year as an instructor in “hard rock subjects” after earning her graduate degree, while continuing to assist Simonds in his courses on general geology, mineralogy and petrography.

She also co-led field trips to Marble Falls, a group of waterfalls that has since been flooded by a dam.

“All over Texas there can be found boys and girls — men and women now — who treasure recollections of this trip with the keenest pleasure,” wrote Simonds in Whitten’s obituary. “For a number of years [Whitten] shared with me the responsibilities of this field day and I am glad to say we never had an accident.”

Another important mentor of early women in UT geology was

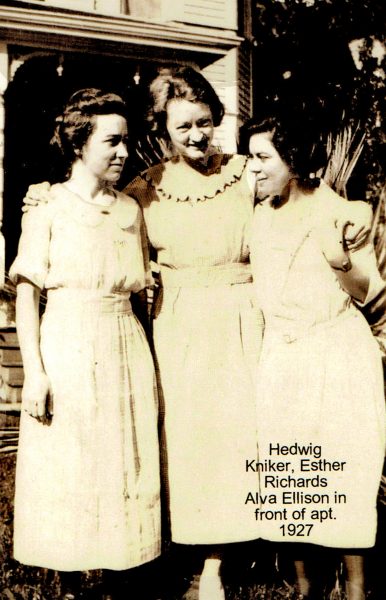

Francis Whitney, the department’s first paleontology professor and third chairman. He advised Hedwig Kniker and Alva Ellisor, whose collaborative research on microfossils in the 1920s revolutionized how oil and gas companies explore for hydrocarbons.

Kniker, who earned her master’s in 1917, was the second student and second woman to earn a graduate degree from the department; Ellisor wrote her thesis, but never received a master’s degree because, according to a note from Kniker in the 1960 Newsletter, she never met the language requirements needed for the degree.

Nevertheless, it’s notable that at a time in U.S. history when women were largely seen as extensions of their fathers or husbands — not being able to vote in federal elections and often prevented from working if married — it was women who wrote the first three master’s theses at the department, an endeavor rooted in independent research and discovery.

Like Whitten, Knicker and Ellisor were also part of the department’s faculty, each serving as instructors for a few years in the late 1910s.

But not all UT students aspired to academia. The 1900s was the “gusher age” for Texas oil, and Reba Masterson — who attended UT from 1908 to 1912 — put her geology education to use as an independent geologist, showing up at new oil wells and offering her geological expertise in exchange for mineral rights.

Her father, Branch Masterson, was the director of two oil companies as well as an independent investor. She likely learned the lay of the land from him, but after graduating from the University of Colorado in 1916, she was in business for herself. Armed with a .32-caliber pistol and her best friend, Eunice Aden, a physical education instructor she met while studying at UT who often acted as a de facto bodyguard, she traveled in her Ford Model T across the South and Midwest scouting out shares in oil and gas leases.

According to family legend, she lost one such lease in a poker game with Columbus Marion “Dad” Joiner, the famed Texas oilman who discovered the East Texas oil field in 1930 (the best-producing field ever discovered in the U.S.).

When she joined the AAPG in 1923, Masterson’s geology experience included conducting reconnaissance work in oil fields in Kansas, Illinois, West Virginia, Pennsylvania, Indiana and Kentucky, and studying the structural geology of Oklahoma, Louisiana and Texas.

According to surviving relatives, Masterson was at Damon Mound Field, a famous Texas gusher that kicked off years of oil and gas production in the area, and, by the time of her death in 1969, had mineral rights in more than 20 Texas counties and a tungsten mine in Colorado.

Reba Masterson (middle row, fourth from left) is one of the six women in the photos.

The Masterson legacy lives on at UT. Her great niece, Amanda Masterson, is an administrative associate at the Bureau of Economic Geology. And her great-great nephew, Wilmer Dallam Masterson IV, earned his graduate degree in geology from UT in 1981 and now works in the petroleum industry.

Gries said that when she learned about Masterson’s work on well sites, she was floored. When she began her career in the oil and gas industry in the 1970s, companies didn’t allow women to work on wells. And yet, here was a woman from the 1910s, showing up at well sites and parlaying her geological knowledge for some skin in the game.

“The history of women being present and competent on well sites had been completely lost and forgotten,” Gries wrote in the introduction of an “Anomalies” chapter on well-site work.

“A new generation of women had to ‘fight for’ the right to well sit — for the opportunity to have a complete exploration geologist’s experience and set of responsibilities.”

The 1970s started to overturn the restrictive gender norms that crystallized during the post-World War II years. But before that, there was a flourishing of women in geology, especially in the area of micropaleontology.

Riding on the heels of the 19th amendment in 1920, which granted women the right to vote, was an era of collaboration and mentorship by the women of UT geology — both students and alumnae.

Foram Revolution

In 1919, E.T. Dumble, a former bureau director and then chief geologist of the Rio Bravo Oil Co., wanted to investigate the connection between macrofossils, such as shells, and Gulf Coast stratigraphy. So, he called the University of California, Berkeley Geology Department looking for a paleontology expert who could spend the summer in Houston conducting research.

“We haven’t a man; Will a woman do?” asked the head of the department. “I don’t see why a woman couldn’t do it better than a man,” responded Dumble.

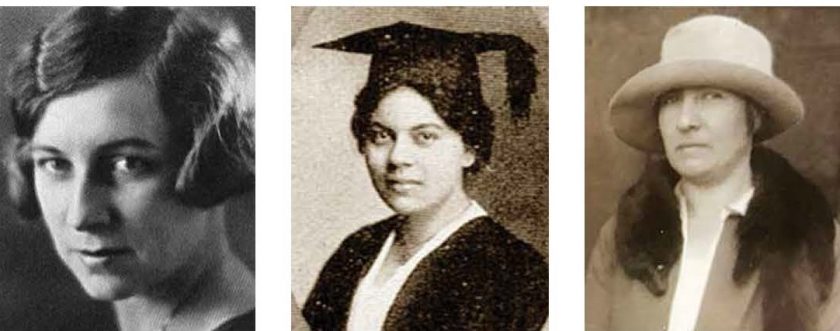

The conversation laid the groundwork for a paleontology renaissance in oil and gas, led by a close-knit group of three women: Esther Richards, a Berkeley graduate, and Hedwig Kniker and Alva Ellisor, both graduates of UT.

Richards arrived in the summer of 1919 to work for Dumble, and was hired on the following year, after she earned her master’s, to conduct research on macrofossils and share her findings with a consortium of four oil companies: Rio Bravo Oil Co., Humble Oil Co., Gulf Oil Co., and the Texas Co. It didn’t take long for two of the companies to hire their own paleontologists. Ellisor went to Humble, and Kniker to the Texas Co.

The companies encouraged collaboration between the women. The women took it further and moved in together.

“It was a splendid arrangement,” wrote Richards in her journal. “We spent most of our evening talking over the day’s accomplishments and problems.”

Macrofossils proved difficult to work with; the drill bit would shatter the specimens, making them hard to distinguish. Ellisor found that a type of microfossil — a single-celled protozoan called foraminifera, or forams — proved perfect for stratigraphy; the variety of types were closely correlated with different geological strata. And their microscopic size made them small enough to avoid the drill bit.

When she told her boss Wallace Pratt, Humble’s chief geologist, about her discovery he told her to keep it a secret. But he couldn’t keep it quiet himself, leaking the news to Richard’s boss, Dumble.

“When I got home, Esther Richards greeted me with the news of my discovery,” recounted Ellisor in the 1962 University of Texas Bulletin. “… Of course, the news of the foraminifera were out.”

But it took some work to convince the larger scientific community of the value of forams — a creature then considered too simple to display the diversity needed to map geologic strata. When Richards presented a paper authored by Dumble on forams at a 1921 meeting of the Geological Society of America, she was immediately challenged.

“I knew that it would take a while to convince people in regard to the value and usefulness of our work,” wrote Richards in her journal. “So, I wasn’t too surprised when Prof. Galloway [of Columbia] got up just after I had finished and said, ‘Gentlemen, here is this chit of a girl right out of college, telling us that we can use Foraminifera to determine the age of formation. Gentleman, you know it can’t be done.”

Four years later, Ellisor, Richards and Kniker let their research do the talking. The three women co-authored a seminal paper in the 1925 AAPG bulletin titled “Subsurface Stratigraphy of the Coastal Plain of Texas And Louisiana” that used forams to unravel the region’s geology.

Their early work turned forams into the gold standard for stratigraphic correlation, a position the tiny fossils maintained for decades until the invention of geophysical well logging and seismic reflection surveys.

Throughout their lives, the three women continued to make important contributions in micropaleontology. Ellisor stayed at Humble her entire career, growing the lab’s personnel and prominence; Kniker started a consulting business and then founded a micropaleontology lab in Punta Arenas, Chile, for what would become the country’s national oil company. She was later inducted into the Jackson School of Geosciences Hall of Distinction in 2008 for her research and philanthropic accomplishments, which include buying 39 of the 56 bells in the UT Tower’s Kniker Carillon; Richards set up a consulting business, had a short stint as an instructor at the UT Department of Geology, and worked for the U.S. Geological Survey.

Both Ellisor and Kniker never married and retained their AAPG memberships throughout their lives. However, Richards’ membership was brief. It ended when she married Paul Applin, a fellow geologist who retained his membership. It was common practice for the memberships of women to end upon marriage, especially if they weren’t working full-time.

Women on Campus

Back at the University of Texas, women were a growing part of the student body. From 1928–1942, women earned 13 percent of master’s degrees, and one of the five doctoral degrees awarded during these years.

Marion Isabelle Whitney, the daughter of Professor Francis Whitney, earned the doctoral degree in 1937, the first woman to earn her Ph.D. from the department.

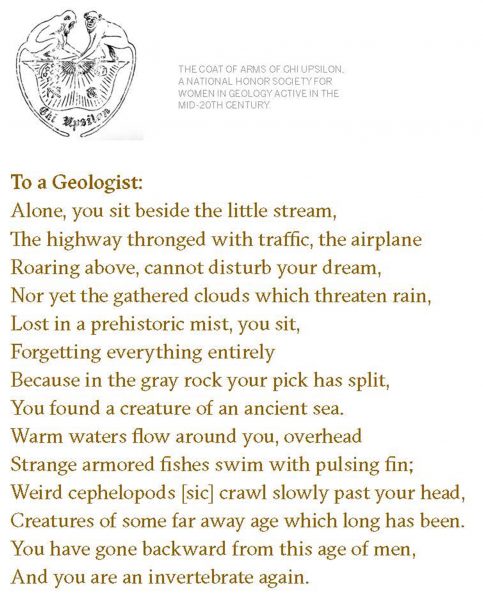

At the undergraduate level, women had enrolled in the department in sufficient numbers by 1926 to revive a UT chapter of Chi Upsilon, a national honor society for women studying geology. Records stored at the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History indicate that the UT chapter had also been active in 1921, and counted both Alva Ellisor and Esther Richards as honorary members.

Membership required being in good academic standing and “interest in geology as a science, as a work, and as a pleasure.”

UT was one of four chapters active during the pre-WWII years, with the others being at the University of Oklahoma, Cornell University and the George Washington University. A society newspaper kept the chapters informed on each other’s happenings, and included original contributions from members. The first issue, released in 1941, is marked with the society’s coat of arms — two monkeys atop a shield marked with a moon and stars, crossed rock hammers, a trilobite, and a mineral — and prefaced by a poem, written by Beatrice Raw, a

member of the George Washington University chapter, that captures the transformative experience of pondering deep time.

Chi Upsilon provided a chance for women to get out into the field, with records showing trips to Enchanted Rock and Hamilton Pool.

However, it couldn’t help with larger institutional barriers at UT banning women from field camp. Until the 1950s, women were not allowed on the weeks-long field geology course, save for one year in the mid-1930s when undergraduate student Marie Gramann “raised a ruckus,” in Gries’ words, so she could earn her Bachelor of Science — a degree that required field camp.

The department allowed her and two other female geology students, Mildred Winans and Katherine Archer, to attend. It then swiftly reinstated its ban on women.

Post-War Years

World War II decreased enrollment in the department for both men and women. College-aged men were off fighting the war, while women supported the effort by taking jobs the men left vacant or by joining the military.

Esther Applin (formerly Richards) commuted from Fort Worth to teach geology classes at UT when several professors went to war. Julia Gardner was a geologist who mapped tertiary beds from Maryland to Mexico, was a key mapmaker for bureau on the first geologic map of Texas, and performed biostratigraphic work for dozens of oil companies in the 1920s and ’30s. During WWII she

joined the U.S. Military Geology Unit and identified beaches in Japan where balloon-borne bombs were coming from by analyzing fossilized shells in the sand used to stabilize the devices.

But once the war ended, many women had to give up their positions. The AAPG membership file exemplifies the point. Before the war, only one or two women were joining the organization each year. However, between 1939 and 1945 — the war years — 50 women joined the AAPG. After the war, only 14 of them remained in the industry.

Female enrollment in the Department of Geological Sciences faced similar issues. From 1943–1973, woman earned only 3 percent of master’s degrees. Kitty Milliken, a senior research scientist at the bureau, conducted research on the history of women in the geoscience department while she herself was a postdoctoral researcher in the department in the 1990s.

Western Natural Gas. She was overseeing her first offshore discovery well.

She found that the participation of women in the department had an early peak in the 1920s through 1940s, when micropaleontology became imperative to oil companies, and then faced a 30-year lull after WWII before beginning to rise again in the mid-1970s.

“It made me realize that what seemed normal to us — to not have many women in the program — was not normal,” Milliken said about her research, which was published in the Journal of Geological Education in 1995. “It was the result of this big disruption.”

There were many reasons why women left the workforce or didn’t enroll in higher education after WWII. Post-war attitudes on working women and an expectation that women would give up their jobs to men limited career opportunities, while the domestic “ideal woman” found on TV shows and advertisements became a figure that many actual women sought to embody.

Gries herself said she looked up to June Cleaver, the suburban mom on the 1960s TV show “Leave it to Beaver.”

“I thought, ‘If I’m like June Cleaver, then what goes with that is this perfect life,’” Gries said. “It meant so much to me for people to say, ‘You’re such a good cook, this is so creative.’ And I love the day I woke up and said, ‘I don’t think I need this anymore.’”

Women who did decide to pursue education or a career had to overcome or tolerate these expectations and biases, and often go along with them to advance their careers.

For example, after earning her bachelor’s in geology in 1950, UT alumna Susan Cage started off her career as a file clerk at Gulf Oil, and after three years of working, was promoted to a geologist. In contrast, when her husband was hired by the same company two years later, he immediately started as a geologist with a salary 60 percent higher than her own.

Cage said that, although not judged on the same standard as her male colleagues, she was able to advance (eventually holding a managerial position) because her geology skills spoke for themselves.

“When you do a good job of it, people are aware of it and that makes a difference,” Cage said. “They liked you, respected you, and that was it.”

However, she mentioned that whenever she joined a new office, she had to start the process of proving herself all over again.

While women were working to advance their own careers, activists in the civil rights and women’s liberation movements of the 1960s and early 1970s were working for equitable treatment of minorities on a larger scale. And in 1972, when affirmative action legislation passed, it impacted the lives of individual women across the U.S, including Cage.

When she retired in 1983, the value of her pension was adjusted so that it was equal to men with the same experience and contributions to the company.

“Sometimes you can change things from within, not fighting the system, just going after your own goals and achievements,” Gries said. “But I sure appreciate the women who made an effort to change things for everyone.”

Reclaiming Spaces

The diversity requirements legislated by affirmative action, combined with the oil shortages of the early ’70s, created high demand for women geoscientists in oil and gas companies. Once hired, women started to push from the inside to open up the industry further.

In“Anomalies,” there are multiple accounts of women challenging company policies that banned them from going on offshore rigs, in underground mines, and on well-sites — places where some men considered women “unlucky” — and pushed against male-only petroleum social clubs and dining suites.

Around this time enrollment of women in graduate studies in the geology started to rebound. From 1974–1993, women earned 27 percent of master’s degrees and 8 percent of Ph.D.s bestowed by the geology department, up significantly from the post-war years.

It was during this revival that current Jackson School Dean Sharon Mosher joined the faculty of the Department of Geological Sciences, the only woman faculty member at the time, accepting a position as an assistant professor in 1978.

Within weeks, she was leading field camp and by the first semester

she was advising four graduate students, and frequently leading field

trips to nearby sites. She remembers a faculty luncheon where the late Bill Muehlberger, a professor in the department, asked her about a fieldtrip she just led.

“The students say you found isoclinal folds in the Llano uplift,” Muehlberger said to her.

The room went quiet. Prevailing wisdom was that the Llano uplift was essentially undeformed with only open upright folds. After describing what she had found, Muehlberger exclaimed, “Well, damn, if she can’t teach us something, we shouldn’t have hired her!”

Mosher became the first tenured female professor in the department in 1990, chair of the department in 2007, and has been serving the school as dean since 2009.

Around the time that Mosher received tenure, in the early 1990s, Pat Dickerson, a Jackson School visiting research fellow, and Pamela Owen, the associate director of the Texas Memorial Museum, were Ph.D. students at the school. They both note that they felt included and accepted by their peers and advisors. Dickerson, who earned

her Ph.D. in 1995, worked alongside Muehlberger, her advisor, training astronauts, including John Glenn, on geological formations that could be documented and studied from orbit.

Owen recounts how Chris Bell, a professor in the department, sought

her out to co-author a paper on a rare fossilized black-footed ferret skull.

“That was the first time that I really felt that I got excellent mentorship researching and writing a professional scientific paper,” Owen said. “He was instrumental in helping me to develop those skills.”

Women Today

The role and prominence of women in the Department of Geological Sciences — and the Jackson School as a whole — have only continued to grow. As of fall 2016, woman made up 42 percent of undergraduate students and 39 percent of graduate students. The school is led by a female dean and women are part of the faculty and research staff at all levels of seniority. And in spring 2017 the school’s advisory council, a group of industry and academic leaders, elected its first female chair, Annell Bay, a department alumna whose own story is part of “Anomalies.” Bay begins her term

in fall 2017.

Following in the footsteps of Chi Upsilon, the women’s honor society of the 1920s, is GLOW, the Geoscience Leadership Organization for Women. The group provides mentorship and support for women in the Jackson School of Geosciences, said President Caroline Nazworth, as well as outreach to students of all ages.

As part of her job at the Texas Memorial Museum, Owen also

frequently participates in geosciences outreach in classrooms. She said that simply letting kids know that she herself is a scientist can make a big impact, recalling how one first grade class said, “She’s a mom!” the moment she walked into their classroom with a trunk full of fossils.

“I think that was their way of expressing, ‘That is not who we expected as the scientist,’ and they were just thrilled,” Owen said. “And it just thrilled me because I totally smashed any preconceived notions of who was coming to talk to them.”

Gries’ “Anomalies” serves a similar outreach function. The collection of stories — many written by individual women themselves — gives women a voice to tell their stories, and provides an array of role models that women didn’t know they had. Most importantly, it shows that women — though not always acknowledged or appreciated — were always part of the story.

“There are no excuses anymore to not know,” Gries said.

Anomalies: Pioneering Women in Petroleum Geology is available for purchase on Amazon.com.For a copy signed by Robbie Gries, please email mkortsha@jsg.utexas.edu. |