FUELING THE FUTURE

October 9, 2017

A group of Jackson School scientists and students embark on a high-stakes research mission

A group of Jackson School scientists and students embark on a high-stakes research mission

BY ANTON CAPUTO

Gulf of Mexico — Standing on the helideck of the Helix Q4000 with nothing but waves in sight, Peter Flemings is bleary eyed and exhausted. But, for this moment at least, the Jackson School of Geosciences professor and chief scientist of the coring mission is relieved and something akin to happy.

The scene marks a seminal moment in a ground-breaking project, an $80-million, multi-year national effort that the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) picked the Jackson School to lead. Flemings and his team have finally hit pay dirt, pulling a core of frozen methane hydrate from about 1,300 feet under the Gulf floor, through a mile of water, and to the deck of the deep-water coring vessel, while still keeping the methane hydrate under pressure.

Under pressure — that’s the important part. Pressure, in many ways, is what this mission is about.

The science crew’s chief goal is to return samples of this ice-like, energy-rich hydrate to the surface of the ship under the same immense pressure it is found in its natural state (about 230 times the pressure found on the surface) so they can begin to unravel

its properties. This involves keeping the pressure on the cores throughout their mile-plus journey up the drill string to the deck of the coring vessel, and eventually through their 500-mile journey to Austin to the new state-of-the-art lab in the Jackson School. The ultimate goal is to figure out how to one day tap the potentially enormous energy resource.

“This is the start of a systematic experimental and theoretical effort to understand the potential to produce methane hydrates in an

environmentally sustainable, safe and economic manner,” Flemings said.

It’s big science. Important science. And it involves lots of pressure.

Flemings and his team have felt immense pressure of their own during the mission, particularly in the early days of coring. They were met with failure after failure when the experimental coring tool didn’t work properly and returned a soupy, muddy mess to the deck instead of the pressurized cores they were seeking.

On this particular day in the middle of the operations the team was feeling relieved, at least temporarily, with the first successful core. But soon after this success, the pressure would return as core after core afterward came back a failure, prompting Flemings to halt operations and consider abandoning the coring altogether.

“We spent the first 10 days out here in a state of complete and utter failure,” he would later remember. “I was within 24 hours of abandoning the expedition and cutting our losses. Each day, we would update our budget and would find us $350,000 further in the hole with nothing to show for it.”

At risk was the future of the project, including a much larger coring mission planned for 2020 in partnership with the International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP). Ultimately, Flemings didn’t abandon the mission but halted operations and instructed the team to do what scientists and engineers do: work through the problem and find a solution — all with the clock ticking and budget mounting.

The pressure was on.

MORE THAN FIRE AND ICE

Much about methane hydrate is a mystery even to the small group of scientists who study it. To the general public, it’s largely unknown. There have been a smattering of news stories about the energy-rich substance, many focusing on the peculiar and entertaining fact that even though methane hydrate appears and feels like ice, you can light it on fire. It’s a trick that is easy to find on YouTube, although it’s nearly always accomplished with a small sample created in a lab, not methane hydrate found in nature.

This much is known about methane hydrate — there’s a lot of it. It is found all over the planet in places where methane is under sufficient pressure and low temperatures, generally under frozen permafrost or beneath the ocean floor.

The substance is made up of water molecules that form a crystal lattice, which traps the methane inside. The dense, ice-like structure holds more than 100 times the energy per unit of volume than methane found at the atmospheric pressure of the surface of the Earth. That’s why people like Jackson School postdoctoral fellow Stephen Phillips made the trip to the Gulf in May, working 12-hour shifts (and often much longer) to set up labs, plot the best coring locations, and process and analyze core samples as they are pulled on deck.

“One liter of methane hydrate down below the seafloor, if you bring it up here, is 160 liters of methane,” said Phillips, smiling from beneath the brim of his ever-present Cubs hat. “But if you bring it up to the surface, it’s basically going to melt and the methane will escape, and you’ll be left with just water.”

This difficult-to-reach methane — the chief constituent in natural gas — represents a potentially vast energy resource for the future, especially for coastal nations with limited resources striving for energy security. Japan, China, South Korea and India, for instance, have active programs trying to tackle many of the same questions as Flemings’ group.

The estimates of how much energy is held in methane hydrate throughout the world vary greatly, but they are enormous. Some estimates contend these deposits hold more energy than all other fossil fuels on the planet combined. Flemings mostly discounts those numbers because they are based on flimsy extrapolations, and so little is really known about the properties and concentration of methane hydrate deposits throughout the world.

In addition, much of the hydrate that’s been studied to date is found in shale and mudrocks, geological formations whose characteristics make recovery more difficult. Flemings’ team is looking at methane hydrate in areas that should theoretically be easier to one day produce.

“What’s different here is that we are directly targeting sand layers that have, we think, high concentrations of methane hydrates,” he said.

That was the thinking when he and a group of like-minded scientists from around the country wrote a proposal to the DOE to core and study methane hydrate in 2014. Back then, the whole proposition seemed relatively straight forward.

“To be frank,” said Flemings, “we had no idea of the complexity of what we were proposing to do.”

UNFAMILIAR SURROUNDINGS

The deck of the Q4000 is an alien and dangerous place for anyone not used to deepwater operations. Jackson School Research Engineer Associate Ethan Petrou is in that group. Petrou, who hails from the United Kingdom, had never been on a large boat before and finds the setting formidable and exciting.

“The actual magnitude of the equipment is insane,” he said. “Humans constructed this. We engineered this. We thought of a way to build a city on the ocean. Seeing it come to life is quite inspiring.”

Petrou is among a handful of young Jackson School scientists who made the trip in May with Flemings, a group that includes two graduate students. Petrou did a year abroad at the Jackson School in 2015–16 where he took Flemings’ energy exploration course. He jumped at Flemings’ offer to join the mission after graduating and is using the experience as an opportunity to judge whether

he’s cut out for a career in energy exploration. His mind is far from made up at this point, but Petrou said he’d definitely go offshore again.

“You can’t really comprehend it until you’re here, but once you get adjusted, life out here is rather fun,” he said. “Everybody is like a little family.”

The vessel itself is a semi-submersible, meaning it doesn’t anchor to the Gulf floor. It stays in one location during operations through the use of a dynamic positioning system that employs six thrusters to continually move the vessel minute distances to keep it zeroed in on the right spot. On deck are massive cranes capable of moving loads of hundreds of tons. The main tower, which is used to build a drill string pipe by pipe to the Gulf floor and beyond, rises more than a couple hundred feet above the deck.

You can’t just come aboard a vessel like the Q4000 when it’s engaged in operations. Every member of the science crew was required to take and pass several certification courses. One focused on teaching you how to react, and hopefully survive, if the helicopter that ferries people to and from the vessel goes down. Another is a basic safety course for simply setting foot on a deepwater vessel. These courses are also required of the crew, although most have training well beyond the basic classes.

The lessons learned in these courses are further drilled into you by the Helix safety team and the crew itself. Among the lessons: always wear full protective equipment on deck and look up before doing anything or going anywhere. A few days of working around the massive cranes instills the sense and necessity of this rule pretty deeply. Another rule: keep your hands off everything except safety rails unless you have a specific need and the correct training. Why? Because everything on deck is metal and massive, and putting your hand in the wrong place could be a potentially dangerous — or even fatal — mistake if a load unexpectedly shifts or powerful equipment starts moving. And finally, if you’re doing most anything on the deck — like say, taking pictures or videos — fill out a permit that explains exactly where you’ll be, when you’ll be there, what you’ll be doing, and what safety precautions you are taking, and get it signed by the officer on duty and the tool master.

In very short order, everyone on the science team seemed to understand that the rules are sensible and important and help instill a sense of order and familiarity in a setting that first seemed chaotic and unrecognizable.

“It’s an interesting environment,” said Jackson School graduate student Kevin Meazell. “You have to focus on safety at all times.”

SCIENCE AND EDUCATION IN THE DEEP WATER

Adapting to life on a deepwater oil and gas vessel is not a seamless process for professors, scientists and students used to the classroom and the lab. The quarters are tight and noisy, the hours are long and the overall setting is unlike most anything the science team had ever dealt with.

There are 24 members of the science team in all. In addition to the Jackson School cadre, there are professors and students from The Ohio State University and Columbia University Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory as well as scientists from the DOE, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and Geotek, a scientific coring company.

Peter Polito, the Jackson School’s methane hydrate laboratory director, has literally spent months preparing for the mission, working countless hours to make sure nothing was forgotten. Now that he’s in the middle of the Gulf, he can only shake his head and manage a scornful laugh at the things he, and the team, overlooked.

“I can’t tell you how many times we’ve called back and asked people to bring things when they come out — power strips, thumb drives, ink cartridges,” he said. “You think about this huge big project and we’ve done all of the big stuff. We’ve done everything we need to pull cores out of the ground, but we need to be able to print plots in real time, we’ve got to be able to take notes, we’ve got to be able to transfer data in a quick and easy way.”

The deck of the Q4000 is about the size of a football field. The only empty space of any size is the green octagon of a helideck that crewmembers use for exercising or playing the occasional game of corn hole in their very minimal free time. It is in this setting that the science crew has set up a series of labs in shipping containers where they conduct the first analysis of the cores as they hit the deck.

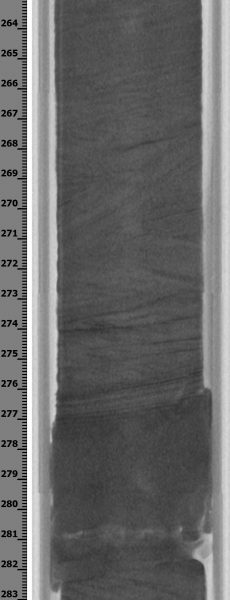

In one container, there’s a workshop where Geotek engineers assemble and repair the specialized coring tool. In another container, there is a large apparatus called the pressure core analysis and transfer system (PCATS) where the cores are transferred to more portable containers capable of holding them under pressure for X-rays and scans of velocity and density measurements.

This is also the area where samples are cut so they can be transferred to other labs on the ship for a first blush analysis. These are places like the mudlab, where scientists prepare core samples for microbiological and chemical analyses.

Another container holds the lab where scientists run quantitative degassing. This involves holding the core in a pressurized vessel and slowly bleeding off the methane hydrate and water into a bubbling chamber, and then carefully measuring as the pressure rebounds. This occurs because the frozen methane hydrate, which is under intense pressure, contains roughly 160 times the methane per volume as it would under surface pressure. As pressure is reduced, the methane hydrate dissociates, or melts, and the methane in the hydrate expands, causing pressure to spike again. By carefully conducting this test over a long period of time, the scientists are able to obtain exact measurements of the amount of methane in the core sample.

“We need to know the amount of methane in the core because it gives us a good metric to quantify how much methane is in the area where we took the core from,” explained Josh O’Connell, lab manager of the UT Pressure Core Center. “And then we can actually extrapolate that out further across the area.”

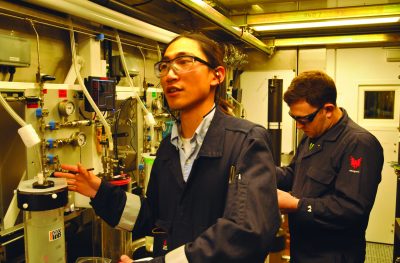

When the first pressurized core came in, the degassing duties were shared among the team through the night and into morning, as members took turns bleeding off the gas and taking measurements every hour. O’Connell and Jackson School Ph.D. student Tiannong “Skyler” Dong pull the first duty. Dong has studied all facets of methane hydrate, and found the process of working with real pressurized cores particularly exciting. This, he said, is when scientists will finally begin to understand if their more theoretical analysis of the substance has been accurate or off-base.

“Usually we just drill a hole and put some sensors into it and take some geophysical measurements,” he said. “With those geophysical measurements, we try to infer the concentration of methane hydrate, but we cannot verify the interpretation. By taking this [gas] out, we can actually know very precisely how much methane hydrate is in the sediment.”

Peter Flemings in the “dog house” watching the drill make its mile-long journey to the Gulf floor through a live feed from the Q4000’s remote-operated vehicles.

When outside the lab, much of the work is being conducted in a cramped office space just off the deck where scientists and students huddle over seismic and borehole data. Theirs isn’t the first trip to the area by a group of scientists interested in methane hydrate. There was a mission here in 2009 to drill and collect some data. Amazingly, the Q4000 was able to find the same hole on the floor of the Gulf with remote-operated vehicles it employs during operations. Postdoctoral Fellow Manasij Santra spent six months pouring over seismic data from this part of the Gulf before boarding the Q4000. He was looking at the acoustic picture of the land under the seafloor, he explained, and closely examining the boundaries of sediment layers for the telltale signs that methane hydrate was present.

“There has been a test in this area, so we know the presence of methane hydrate and what we see in the seismic data also matches that,” he said. “We really think we will get methane hydrate in this area.”

All the tests being conducted are first-order science to determine not only the concentration and amount of methane hydrate in the sediment, but how it will react or change when depressurized in the event the methane is ever harvested.

Beyond the science, the mission, Flemings said, offers a learning environment for students and young scientists that no classroom can match. The multidisciplinary nature of ocean drilling is like few other settings. It brings together geology, geophysics, chemistry and engineering.

“By them being in the middle of this and seeing how all these pieces fit together, this is an environment that literally drives students to whole different levels,” Flemings said.

Petrou was particularly struck by the experience of being part of a team that was collecting data directly in the field and then working with it in real time, an experience not often replicated in an academic setting.

“It’s definitely helping me grow as a scientist,” he said. “To actually see things I’ve read in text books. I’m developing new ideas and talking to people I never would have come in contact with. It’s definitely given me a lot of ideas to think about.”

The extreme deadlines placed on the students to plot data in real time and come up with solutions to critical problems, is also a driving force in their education, said Flemings.

“You need to make a decision, and you have to come up with your best estimate or your best analysis in the time you’ve got, and that’s it,” he said. “I can see the students, they’re like, ‘Holy cow, now Flemings is asking me where to locate exactly where to drill on the ocean floor. No one has ever asked me to do that before and that’s a multimillion-dollar decision. I better not screw it up.’”

The young scientists aren’t the only ones learning. Flemings, who has been on many drilling missions and sports more than a few gray hairs, said the mission has stretched him in surprising ways.

“The logistics and the paperwork alone associated with getting a vessel like this to come to the middle of this particular spot is challenging in a way I never imagined,” he said. “It’s like trying to grab a hold of a bear. It sort of overwhelms you, just planning the pieces and keeping the things from falling off the tracks.”

TURNING IT AROUND

May’s coring mission was a trial of technology and methods pioneered to bring up samples of methane hydrate under the same pressure and temperature where they are found under the seafloor. The tool being used is called the pressure core tool with ball valve, or the PCTB for short. It’s basically a long tube that is lowered within the pipes of the drill string and pulled up the same way after it has retrieved a sample. It is capable of coring samples about 10 feet long. But in order to retrieve the cores under pressure, the ball valve must close correctly to seal the container, and a nitrogen boost within the container has to fire.

The team tested two versions of the tool on land at Schlumberger’s test facility in Cameron, Texas in December 2015 before taking them to the Gulf. After all the preparation, Polito said the team was flush with optimism. That optimism was soon tempered in the

deep water, as the tool failed on all but one of its eight first attempts.

“You have this expectation because you’ve been planning it so long that you’re going to get 20 cores,” Polito said. “You don’t stop to think about how difficult this really is.”

But before the mission was over, the team would engineer an amazing turnaround, pivoting from almost universal failure to overwhelming success.

“Engineer” is the key word. When Flemings called a halt to operations mid-way through the coring expedition, the team scrambled to try to determine what was going wrong. They dug deep into the data, looking for clues that might reveal the source of the problem. They studied images of the tool as it came out of the bore hole, looked at sediment in the tool’s moving parts, and

poured over engineering drawings.

While they were doing all this, the crew of the Q4000 was logging and cementing the first borehole and moving to the second coring location. It would take 30 hours. That’s how long the science team had to come up with a solution. The chosen fixes involved: grinding grooves into a component of the tool assembly that was binding and restricting high-pressure fluid from passing through; replacing the ball valve seal in an attempt to achieve a tighter fit; and welding small tabs onto teeth-like grabbers that pull the core liner inside the tool as the ball was closing in an attempt to keep the liner from slipping and obstructing the ball valve.

“We must have done something right because after that change, we had nearly 100 percent core recovery,” Flemings said.

Polito was even more succinct.

“Thank God,” he said.

Ultimately, the team brought up just over 90 feet of pressurized core to analyze, process and cut on the ship. Afterwards, they continued their work for two weeks in Port Fourchon, Louisiana, where the science facilities were relocated after the mission.

From there, 21 pressurized cores of between one to three feet long were loaded on a truck and brought to the Jackson School, where Polito and O’Connell wheeled them into the newly built UT Pressure Core Center. This is where an integrated team of scientists and engineers from the Jackson School and UT’s Department of Petroleum and Geosystems Engineering will continue their research. At the heart of the analysis is a desire to understand the dynamic evolution of hydrate reservoir properties as methane is extracted.

The Jackson School will be the hub of the ongoing work, but it’s a national effort. A multidisciplinary team of scientists from institutions around the country is also joining the research. Depressurized core samples recovered during the mission have been sent to The Ohio State University, University of Washington, University of New Hampshire, Oregon State University, ExxonMobil and USGS. Eventually, pressurized cores will be sent to the USGS in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, to the DOE National Energy Technology Laboratory, and perhaps other locations.

“I’m really excited for the science that’s going to come out of this,” Polito said. “A year from now I’m going to know things that no one knew today. That’s really exciting to me.”

Now that the cores are safely in the Jackson School’s lab, the real work is just beginning. Still, Flemings can’t help but think about how close the line is between success and failure when trying to pull off something big, especially when the pressure is on.

“I guess what I learned, once again, is that unbelievable focus and really, truly working the problem can lead to amazing achievements,” he said. “When everybody truly gives their all to make it happen, you can actually pull these things off.”

Back to the Newsletter