Grinding Down Mountains

October 11, 2016

Researchers for the first time have attempted to measure all the material leaving and entering a mountain range over more than a million years and discovered that erosion caused by glaciation during ice ages can, in the right circumstances, wear down mountains faster than plate tectonics can build them.

The international study conducted by the Integrated Ocean Drilling Program and led by scientists from the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics (UTIG), University of Florida and Oregon State University, adds insight into a longstanding debate about the balance of climate and tectonic forces that influence mountain building.

The research was published on Nov. 23, 2015, in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

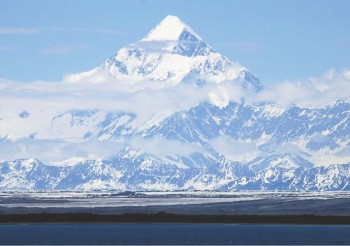

Researchers studied the St. Elias Mountains on the Alaskan coast and found that erosion accelerated sharply about 1 million years ago when global climate cooling triggered stronger and more persistent ice ages than times past.

They used seismic equipment to image and map a huge fan of sediment in the deep sea in the Gulf of Alaska caused by erosion of the nearby mountains and took short sediment cores to understand the modern system. They then collected and dated almost four kilometers of sediment from the floor of the gulf and the Alaskan continental shelf, revealing millions of years of geologic history.

“It turned out most (sediments) were younger than we anticipated, and most rates (of sediment production and thus erosion) were higher than we anticipated,” said lead author Sean Gulick, a research professor at UTIG. “Since the big climate change during the mid-Pleistocene transition when we switched from short (about 40,000-year) ice ages to super-long (about 100,000-year) ice ages, erosion became much greater.”

Since the mid-Pleistocene, erosion rates have continued to beat tectonic inputs by 50 to 80 percent. The study was funded by the National Science Foundation and the Integrated Ocean Drilling Program.

Back to the Newsletter