Natural Underground CO2 Reservoir Reveals Clues About Storage

October 20, 2014

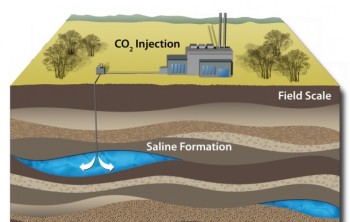

Reducing our emissions of carbon dioxide quickly enough to minimize the effects of climate change may require more than just phasing out the use of fossil fuels. During the phase-out, we may need to keep the CO2 we’re emitting from reaching the atmosphere—a process called carbon capture and sequestration. The biggest obstacle preventing us from using CCS is the lack of economic motivation to do it. But that doesn’t mean it’s free from technological constraints and scientific unknowns.

One unknown relates to exactly what will happen to the CO2 we pump deep underground. As a free gas, CO2 would obviously be buoyant, fueling concerns about leakage. But CO2 dissolves into the briny water found in saline aquifers at these depths. Once the gas dissolves, the result is actually more dense than the brine, meaning it will settle downward. With time, much of that dissolved CO2 may precipitate as carbonate minerals.

But how quickly does any of this happen? Having answers will be key to understanding how well we really sequester the carbon.

They’re difficult questions to answer accurately, because it really requires working with the complex environment of those deep, saline aquifers—not exactly the most convenient laboratory. A new study led by Kiran Sathave of the University of Texas at Austin takes advantage of a natural CO2 reservoir to learn more.

Ars Technica, October 20, 2014

Featuring: Kiran Sathaye, Ph.D. candidate in the Jackson School of Geosciences