Groundwater Depletion and Cocktail Parties

March 20, 2013

Groundwater depletion is a massive problem worldwide, but aside from hydrogeologists and farmers, how many people are aware of it?

This year’s Oliver Distinguished Lecturer, Tom Gleeson of McGill University, wants to make sure both the problem and its potential solutions are well understood—so well understood, they can even be explained at a cocktail party.

“If nothing else, I would like for you to come away from this lecture with at least two or three interesting facts about groundwater that you could use in a conversation at a cocktail party,” he quipped. To make it easier, several of his slides had a little picture of a cocktail glass next to an interesting fact or figure. For example, did you know it takes 140 liters of water to grow a cup of coffee? Or that 99 percent of the fresh, unfrozen water on the planet is groundwater?

Gleeson’s cocktail party facts underscore a looming crisis. According to Gleeson, about 1.7 billion people rely on groundwater resources that are being used faster than they are being recharged.

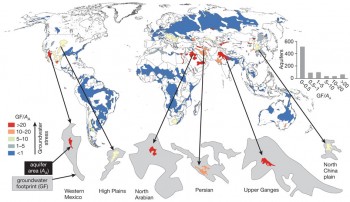

In a Nature journal article last year, Gleeson and his co-authors coined the term “groundwater footprint” to refer to the area required to sustain groundwater use and groundwater-dependent ecosystem services of a region of interest. In the case of an aquifer, it’s how large the aquifer would have to be to sustainably support the actual human use and ecosystem services that rely on it. They found that 20 percent of the world’s major aquifers are smaller than their groundwater footprints, including the High Plains Aquifer (U.S.), the Western Mexico Aquifer, the Upper Ganges Aquifer (India and Pakistan), and the North Arabian Aquifer (Saudi Arabia).

Gleeson offered four possible solutions for groundwater depletion:

1. Think multi-generationally, but act on a political time scale. Gleeson said we should have a long-range plan to ensure water availability, but be aware that decision makers don’t like to think ahead more than a few years. So set a goal for the water table height you’d like to have a century from now and then use a simple hydrologic model to “backcast” and figure out what actions you would need to take over the next 5 to 10 years to get on the right path toward that goal.

2. Let the locals take charge. Gleeson said water management should be integrated, adaptive, inclusive and local. He described a group of farmers in a drought prone region of India who formed a committee to monitor rainfall, water table height and water pumping rates and who then set pumping limits on themselves accordingly.

3. Value groundwater differently. “Some commodities are too precious to be valued merely economically,” said Gleeson. For example, he noted that groundwater provides an important buffer against climate change-induced drought, something that’s hard to put a dollar amount on.

4. Decrease net groundwater use. Use it more efficiently, set limits on pumping, harvest rainwater, and artificially recharge aquifers during times of excess surface water.

“The take home message is that groundwater is a large, valuable reservoir of clean water and we’re depleting it,” he said. “But there are real solutions and tools to stop or reduce depletion.”