Scratching the Surface: Hydrogeologists Study Human Impacts on Pacific Island Reef

August 23, 2011

Do you ever dream of taking a few days off and getting away from it all? Burying your toes in some warm sand and just staring out at the ocean? Rarotonga, one of the Cook Islands in the South Pacific, is about as far as you can get.

“With its jagged peaks and deep valleys, fertile slopes of red earth and sparkling aquamarine lagoon, [Rarotonga] is the classic 19th century European ideal of paradise,” proclaims a Cook Islands booster website. It goes on to describe an idyllic scene with coconut palms, the roar of the waves, and the beat of the drum dance.

Sounds lovely right? But head to the shore with a careful eye and another reality intrudes. Sadly, the part they don’t mention on websites and in slick brochures is that the coral reefs are largely dead.

“Tourists go there and see nice beautiful white sand and turquoise water,” said Bayani Cardenas, associate professor in the Jackson School of Geosciences. “It’s not supposed to look like that. Some parts are supposed to be sharp, rocky reefs with colorful fishes.”

Cardenas should know; he grew up in the Philippines. Reefs there have been badly degraded in part due to overfishing and too many commercial fish pens. But he suspected people could be impacting the reefs in more indirect ways.

A study he and his colleagues published three years ago showed that a significant amount of fresh groundwater beneath Santiago Island was flowing offshore and seeping from the sediments and reef rocks into the sea, most likely through geologic faults. Several farmers live on the island. Although Cardenas didn’t trace the sources, he suspects sewage and fertilizer runoff transported in the groundwater is affecting the reef. The added nutrients could feed algal blooms, deplete oxygen from the water, and kill coral and fish.

Researchers from Southern Cross University in Australia saw Cardenas’ work and invited him to join a study on Rarotonga. They already planned to measure salinity and nutrients in the water over and within the reef to better understand why it had become degraded. Cardenas would use his geophysical tools and hydrogeologic background to help determine where freshwater and nutrients were coming from. It wasn’t clear if the freshwater was flowing overland or was taking a more complicated subsurface path.

Cardenas and two doctoral students flew to Rarotonga last February. The leading hypothesis, the one they hoped to test, was that raw sewage from the population of 16,000 and many thousands of tourists each year, as well as from hog farms, is carried in shallow groundwater down the steep volcanic topography to the coast, emerging from the floor of the lagoon through sediments and cracks in the reef itself, much as in the Philippines.

Kevin Befus had been at UT for a few months and was casting about for a PhD project when Cardenas invited him to participate in the project. The trip was so successful, the data so plentiful, that he decided to make it the focus of his PhD. Now he’s analyzing the data, using it to create a hydrologic model of the island, and planning future work.

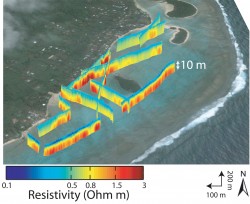

Cardenas, Befus and PhD student Travis Swanson pedaled an experimental catamaran around the lagoon off the southeast coast of the island towing electrical resistivity (ER) equipment, which they used to map areas below the seafloor with freshwater, seawater, or some mixture. They collected corresponding ER data below the land surface. They also measured water temperature in wells near the coast at various times as tides came and went to get a sense for how the movement of freshwater ebbed and flowed in response to the movement of seawater.

They found fresh groundwater below the land was indeed flowing out and seeping up through the reef. In fact, much to everyone’s surprise, this seepage was detected as far away as the edge of the reef, half a kilometer from shore.

“Before this work, the Australians thought the freshwater was coming out close to shore,” said Befus.

Cardenas and Befus propose this unhealthy brew is a result of an unfortunate blend of natural factors—including steep island topography that gives groundwater the gravitational oomph to move far out onto the reef and the presence of fractures that act as conduits—and human factors—such as the development of pig farms catering to the tourism industry and the lack of any real treatment for human or animal waste.

“They are in the middle of nowhere, they rely entirely on tourism,” said Cardenas. “It’s their main industry. Their problem now is they just have domestic septic systems. All their waste goes in their backyards and then some gets into the rivers and aquifers.”

Befus would like to extend the offshore component of the study to the entire island (this study focused on just 2 out of about 30 kilometers of coastline). That would allow him to build a complete hydrologic model for the entire island accounting for every drop that comes and goes. Ultimately, that would allow him to provide the local community with some general guidance on which areas on the island might be the largest contributors to this submarine groundwater discharge, the term hydrogeologists use for this kind of flow. That information could help islanders decide where to build water treatment facilities or where to restrict certain kinds of land use.

Befus, who grew up in Latin America, first got interested in water during an undergraduate hydrogeology course. The professor, James Clark, was focused on international water development. Clark, who became a mentor to Befus, would go to places like Tanzania or Chad and use geophysical instruments to help locals find the best places to drill for water. Befus was inspired to volunteer with a student-led project building gravity fed water systems in Honduras. Now as a PhD student at UT Austin, he talks to his fellow students about participating in similar projects.

“We are geologists,” he said. “We have a certain skill set that we can bring to these communities. So I’m trying to get people excited about it.”

by Marc Airhart