Fossil Time Capsules: Unwrapping Depression Era Fossil Stashes Yields New Discoveries

February 2, 2011

Let’s say you’re a budding young paleontologist looking to make your mark. The first thing you have to do is pack up your shovel and pick, head out into some remote badlands, and find yourself a bunch of fossils that no one has ever seen before.

Let’s say that doesn’t pan out. You might have better luck digging in the basement.

On the eve of America’s entrance into World War II, dozens of workers were out collecting fossils in counties all over Texas. They were part of a survey funded by the Work Projects Administration (WPA) and managed by Elias Sellards, the director of The University of Texas at Austin’s Bureau of Economic Geology.

When war finally came, many of the workers traded in their picks for rifles. Over two and a half years, they had collected more than 11,000 vertebrate fossils and shipped them back to the university. They found reptiles, amphibians, dinosaurs, and more. The field work ground to a halt and a mountain of potential research was shelved.

A small portion of the specimens were prepared and studied, and an even smaller portion of those were eventually put on display in the Texas Memorial Museum on the main university campus. The majority are stored away in the Vertebrate Paleontology Laboratory (VPL) in north Austin.

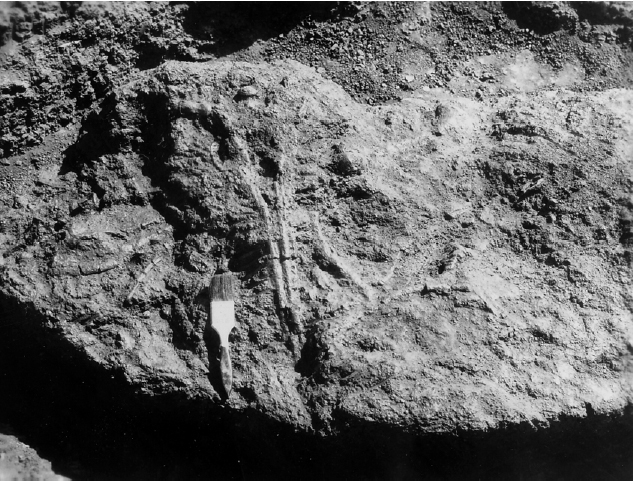

The WPA collections include at least 41 “jacketed” specimens, blocks of rock and fossil still encased in the white plaster jackets they were wrapped in to stay intact on their journey back to Austin. They range in size from dinner plates to refrigerators. While notes and photographs still exist relating to the contents, no one has seen what’s inside for 70 years.

“A lot of people died and the world was different after the war,” says Tim Rowe, director of the VPL and professor in the Jackson School of Geosciences.

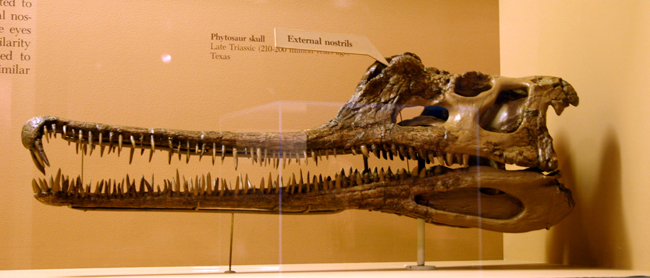

Now a doctoral candidate has opened up the largest WPA jacket and is carefully removing and preparing a remarkably complete and well preserved skeleton of an ancient relative of crocodiles. The animal was only known from skulls before, so her description of the rest of it will fill an important gap. It also comes from a legendary fossil site with many more secrets left to reveal.

Triassic Treasures

In Howard County in West Texas, the WPA workers hit paleo pay dirt at one of only a handful of high quality fossil sites from the Late Triassic in North America.

“That’s a time zone we know very little about,” says Rowe.

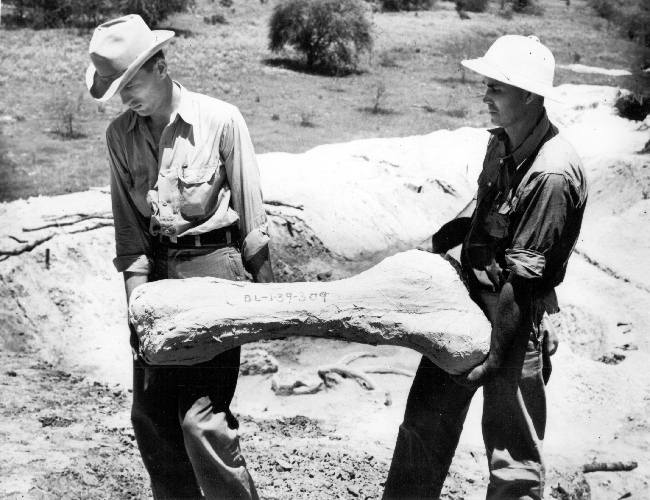

The WPA workers collected thousands of specimens from Howard County. They found crocodile-like animals, dinosaurs, and amphibians. Many were species new to science, including Trilophosaurus buettneri, a lizard-like reptile. Some of the jacketed specimens weighed over 1,000 pounds.

“The physical labor that went into that was immense,” says Rowe. “You can tell these guys wanted it really bad.” He notes that $220,000 was spent on the effort, an astronomical sum in Depression Era dollars.

Only a few people involved in the survey were career paleontologists. Following the war, they mostly scattered to other institutions. Postdoctoral researcher Joseph Gregory went on to became a professor at the University of California at Berkeley, and eventually became director of the University of California Museum of Paleontology. One of the last living people involved with the WPA survey, Glen Evans, died last year.

Michelle Stocker is the doctoral candidate in the Jackson School preparing and studying the jacketed specimen. Because her specimen hails from one of the oldest Late Triassic sites in North America, it entombs animals that are in some sense earlier, less evolved versions of animals found in later sites, says Stocker. She’s comparing the complete assemblage of animals from Howard County to another area to look at changes in diversity and faunal composition through time and across space. She focuses on specific clades, or groups of related animals, such as Archosaurs, a clade containing dinosaurs, birds and crocodiles.

“Knowing the more primitive members of all those clades gives you a better idea of how those members are related to each other because they don’t have their own special derived characters already confusing the relationships,” she says. “They have more of the shared characteristics of the larger group they belong to and you can tie them together more easily.”

She said the sheer number and diversity of fossils from this time period make it even more useful.

“So it gives you a really detailed picture of the fauna in that part of the Late Triassic that you don’t get well in other places,” she says. “It’s amazing to see such an abundance of specimens and taxa from one place.”

For many years, land owners were reluctant to allow researchers back onto the land to continue the research. But as 2010 was drawing to a close, Stocker and her paleontologist husband were granted permission to do field work at the original WPA sites. They planned to go out in February to relocate each of the original WPA localities and fully document them with digital photographs, GPS readings, and detailed notes. They also planned to search for more fossils and to apply modern dating techniques to the soils to better constrain the ages of the fossils.

Light of Day

Three of Stocker’s colleagues hoisted the 7 foot long plaster jacket weighing over 1,000 pounds off the VPL’s basement floor with a crane lift. They brought it up to the ground floor through a trap door, rolled it over to the preparation lab and set it on a large table. With a pocket knife, Stocker and Sebastian Egberts, a former assistant preparator, cut through the plaster and burlap, revealing a block of reddish mudstone.

“We opened the jacket the way you would open a tin can so that we could ‘peel off’ the top while still maintaining the structure of the side walls for support,” she says.

That was in fall 2008. Two years and hundreds of hours of careful picking and chipping later, she and the occasional volunteer have freed the entire skull and much of the vertebral column of a juvenile phytosaur named Angistorhinus. From a distance, the live animal would have looked a lot like a modern crocodile. She estimates it was about 10 to 13 feet (3 to 4 meters) long from snout to tail and lived around 220 million years ago.

More of the vertebrae, leg bones, and ribs remain to be prepared, as well as a second unopened jacket that is thought to contain the tail and perhaps parts of the pelvis.

The work has been slow and difficult, but Stocker says three things make this specimen stand out for someone interested in the evolution of tetrapods (four legged animals) in the Triassic. First, it includes parts of the body never seen before for Angistorhinus, including ribs, vertebrae, limbs, and tail. Second, the vertebrae are fully articulated, an uncommon situation that improves the accuracy of reconstruction. And third, it is a juvenile, which sheds light on how phytosaurs’ bodies changed as they matured.

The discovery also fits in nicely with Stocker’s larger dissertation project mapping which animals lived when and where in the Late Triassic of North America, and how they relate to each other in evolutionary terms.

Jack in the Box

It’s surprising how much fossil material is wrapped up and squirreled away just beyond reach in museums and university collections around the world. Any place with a large collection going back several decades has them.

The American Museum of Natural History in New York has still-jacketed specimens collected in the 1910s in Alberta, Canada by Barnum Brown, world famous paleontologist who also discovered the first remains of Tyrannosaurus rex. Carl Mehling, collections manager for vertebrate collections, reckons they have hundreds of unopened jacketed specimens in all.

Even here at UT Austin’s VPL, in addition to the 41 WPA jackets, there are crates of dinosaur fossils given to the university by the American Museum in the 1930s for the Texas Centennial Exposition. The fossils, originally unearthed in 1903, ultimately required too much preparation to display. The jacketed blocks, which range from football to desk drawer-sized and weigh hundreds of pounds, await their time in the sun, still packed in straw in their original wooden crates, made of rough hewn timbers nearly a foot thick.

So you might be thinking, good grief, why doesn’t someone just pop those suckers open and see what’s in them? Paleontologists love fossils. They’re hyper curious by nature. What’s stopping them?

Ask anyone who manages these collections, and they’ll give you the same reasons. It’s much easier to get grants and excite graduate students to go on exotic field trips than to prepare fossils. Fossil preparation is much slower and harder to do than field collection. You have to sit for hour upon hour, day after day, chipping grains of rock from a specimen under a microscope. Lots of people are good field collectors, but few have the patience and dexterity to be good preparators. So backlogs are inevitable.

Other factors make it easier to just leave them be, says Wann Langston, emeritus professor in the Jackson School.

“As long as they are wrapped up in their jackets, they aren’t going to get damaged or lost,” he says. “If they’re opened up and there’s nothing of interest to the individual, they lie around for a while and things happen.”

Paleontologists look at the dusty old jackets the same way a cautious child might consider a jack in the box.

“When you unpack something, it grows,” says Mehling. “You can stack jackets, but you can’t stack prepared specimens. You have to store them in drawers and trays with foam. And in this business, space is always an issue.”

Like every area of science, paleontology has become highly specialized. Ernie Lundelius, emeritus professor in the Jackson School, says a researcher isn’t going to open up a jacket unless he or she is confident it will further their own research.

“There’s just not enough money to open and clean them up just to clean them up,” he says. “They’re usually tied to some research project. That’s true of Michelle and her phytosaur because she’s interested in that specific group of reptiles from the Triassic. If I were to cut into a great fortune of a billion dollars, I’d say lets clean all of them up and see what we’ve got.”

A New Generation

Now a new cohort of young paleontologists are making opening these jacketed specimens an integral part of their research. And it’s paying off handsomely.

Sterling Nesbitt, a graduate student at Columbia University with a keen interest in Late Triassic animals, heard the American Museum had jacketed specimens collected in the 1940s from a legendary fossil bone bed on Ghost Ranch in New Mexico. He saw one labeled “phytosaur” and decided to open it up. Because there were no photos or accompanying notes to provide more details, it was a bit of a leap of faith. That jacket and others collected nearby turned out to contain a new species closely related to crocodiles, but which had co-evolved traits similar to some dinosaurs.

Nesbitt’s work upended scientists’ view of what the Ghost Ranch quarry actually represents. It was thought that the quarry was the result of a mass die-off of just one kind of dinosaur, Coelophysis. Nesbitt showed a lot of other animals died there too. His work on already-prepared specimens from the same location also dispelled earlier notions that Coelophysis was a cannibal.

After receiving his doctorate, Nesbitt joined the Jackson School as a postdoctoral researcher. He’s now a postdoc for the University of Washington, while continuing to work in the collections at UT Austin’s VPL.

Fortunately for Stocker, she had some idea of what was in her WPA jacket before she even opened it. There were surviving photographs from when it was collected and a letter from its discoverer, Grayson Meade, about what he thought was there.

“The new quarry is looking damn good,” wrote Meade to his colleague Glen Evans in May 1940. “[W]e have found quite a portion of a partially articulated phytosaur skeleton. About four or five feet of the vertebrae are mostly in articulation. There are leg bones, some ribs, and the mandible. … There is every indication that the skull should be there, and more of the skeleton. I didn’t reach the end of it knowingly at any rate.”

by Marc Airhart

Also See:

Vertebrate Paleontology Laboratory

For more information about the Jackson School contact J.B. Bird at jbird@jsg.utexas.edu, 512-232-9623.