Evolutionary Treasure: University Scientists Scan Lucy, World’s Most Famous Fossil

August 20, 2009

An estimated 210,000 people came to the Houston Museum of Natural Science to glimpse the world’s most famous fossil, Lucy, the remains of an ancient human ancestor who lived 3.2 million years ago. It was the first time Lucy had left Ethiopia in 30 years.

She lay in a glass case on a pedestal in the center of a dim room, each bone fragment cradled by recesses in a black foam bed and glowing in the beam of accent lights. Her place of honor in the museum befitted her scientific significance, having revealed key insights into how humans evolved. Her new surroundings would have been completely alien to her, like Joan of Arc beamed up to the Starship Enterprise. One visitor commented that it seemed like a miracle that these fragile pieces of fossilized bone survived for millions of years and were ever discovered, sitting in the dirt in the harsh environment of northeast Africa where one good rainstorm can scatter fossils across the landscape and wind and sand can polish them to oblivion.

In September 2008, after a year on display, Lucy was carefully packed up and shipped off to Seattle for the second public stop on a grand tour of the U.S.

What most people didn’t know is that after leaving Houston, this ancient and irreplaceable fossil took a little detour along the back roads of Texas. For 10 days, in a non-descript basement on the University of Texas at Austin campus, scientists carefully analyzed the fossil fragments with equipment that would have made television’s CSI team jealous.

Slice by Slice

Most people are familiar with the medical instrument known as a CT (computed tomography) scanner, a device for making three-dimensional images of the inside of the human body. The patient lies inside a cylinder and an x-ray source rotates around their body, shining a beam through the patient to a series of detectors. A computer collects a series of “slice” images and combines them into a 3D image that can reveal- without surgery-tumors, blocked arteries, kidney stones, and other features of medical interest. Scientists also use specialized CT scanners to investigate the insides of geological, paleontological, and cultural objects without cutting into and damaging them.

Scientists at The University of Texas at Austin’s High Resolution X-ray CT Facility (UTCT), which is housed in the Jackson School, have scanned thousands of objects, many of them one-of-a-kind and irreplaceable, such as the braincase of Archaeopteryx (the oldest and most primitive bird known), one of the first books printed in the New World, a Martian meteorite believed by some to contain signs of alien life, space probe thrusters, and diamond-encrusted rocks from deep inside Earth. The UTCT, a National Science Foundation shared multi-user facility, houses the first industrial CT scanner in a science department anywhere in the world.

Rich Ketcham, an associate professor in the Jackson School of Geosciences and director of the UTCT, headed the technical team that scanned Lucy.

|

The Girl With The Kaleidoscope Eyes It’s widely known that Lucy got her name from a Beatles song, “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds.” Less well known is the way the song helped make it possible to CT svan Lucy 34 years lster.

|

“We have more experience scanning natural history objects and dealing with the issues that can arise in scanning natural material than any other lab in the world,” said Ketcham. “The equipment is constantly updated and we’ve created a large, specialized toolkit to process the scan data and to extract the maximum amount of information from it. There’s no other place the Ethiopian government could have sent Lucy to get better imagery or to acquire it more safely.”

The set of fossils making up Lucy are about 40 percent complete, and for years she has been considered the oldest and most complete fossil skeleton of any adult, erect-walking human. (As this article was going to press in fall 2009, scientists published their evaluation of a comparably complete fossil skeleton of an even more ancient and primitive human ancestor nicknamed Ardi.) Lucy represents a distinct species of human ancestor, known as Australopithecus afarensis, meaning “southern ape of Afar,” referring to the region in Ethiopia where the fossils were discovered. The hominid fossil record is patchy, but it’s thought that A. afarensis thrived from about 3.7 to 3 million years ago. Since then, several hominid species emerged and died out leaving only us Homo sapiens. Seeing Lucy in person, many people make an emotional connection. She becomes a tangible part of our own history.

Evidence from fossils and DNA suggest that modern humans and our closest living relatives, the chimpanzees, evolved from a common ancestor around 6 or 7 million years ago. Two of the characteristics that set us apart from chimps are our relatively big brains and our ability to walk upright for long periods. Before Lucy, anthropologists debated which came first in human evolution. Lucy turns out to have been an upright walker with a relatively small brain, which indicates that larger brains came later.

Ketcham and others hope the latest scans of Lucy will reveal even more about how she used her arms and legs and what she ate. They’ve combined the slices into three dimensional models of each fragment. They can rotate those models on a computer screen, fly through them, and measure different features. They can start to answer questions that weren’t possible before. Plus, they can safely make castings-often a dangerous process-without touching the originals.

Even with the great track record of the UTCT and all the amazing items that have come through the door, Ketcham said Lucy just might top them all.

“It’s the most famous fossil in the world,” he said. “Everybody’s going to see the scanned data and everyone is going to know it got scanned here. It doesn’t get bigger than that.”

If Bones Could Talk

Ketcham has collaborated for several years with John Kappelman, a professor of anthropology at the university. Working on a range of primates, they’ve studied trabecular bone, spongy material inside bones that makes them both light and strong.

“If you’re a meat eater and you’ve ever cut through a piece of steak with a bone on it, chances are you’ve seen spongy bone in the middle of a bone cross section,” said Kappelman.

Its orientation varies depending on how the bone is used during life and what forces it experiences. The two researchers have studied spongy bone in a wide range of primates learning, for example, how it looks in the arms of an animal that spends lots of time swinging from tree branches or how it looks in the legs of animals that leap.

“The high resolution CT scan permits us to look at those orientations of the spongy bone in three dimensions and we can then estimate the forces and orientations of the forces that passed through those limbs,” said Kappelman.

Lucy clearly walked on two legs, which suggests she spent a lot of time on the ground. But her bones reveal some traits more similar to tree-dwelling primates. Now, by looking at the spongy bone in Lucy’s arms and legs, Ketcham and Kappelman have a rare opportunity to better understand how she used her limbs. Kappelman said even more clues can be derived from studying the thickness of denser cortical bone in the long bones of the arms and legs.

“So we can learn whether she was doing more pulling up when she was climbing or hanging somewhat when she was in the trees and also the kinds of forces transmitted through the leg when she was walking,” said Kappelman.

Ketcham said Lucy’s teeth might also reveal clues about what she ate. He noted that each tooth has now been scanned in three dimensions at a resolution of about 30 microns, roughly the thickness of a human hair.

“We’ve given Lucy the best dental x-ray in history,” he said.

Handle With Care

The UTCT is on the bottom floor of the Jackson Geological Sciences Building on the main university campus in Austin. Its location among other labs and storage rooms is so discrete that visitors sometimes have a hard time finding it. A special alarm system and safe were installed and security guards were hired just for Lucy’s visit. The fossil’s presence was a secret to all but a handful of people involved with the project.

It took Ketcham and his colleagues 10 days to scan Lucy’s 80 bone fragments, working nearly around the clock with two scanners-one for larger pieces and another for smaller ones. To scan each piece was an elaborate process:

First, they measured, weighed and compared a piece to reference images to be sure that it had not been damaged in transit. The fossils were only directly touched by an Ethiopian handler.

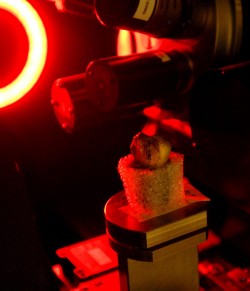

Second, they made a custom foam mount for each piece, or sometimes a set of smaller pieces, so it could safely sit and rotate in the CT scanner without being damaged and to dampen vibrations that would blur the images.

Third, they placed the fossil fragment in the scanner and shut the heavy lead-shielded door. Inside, an X-ray source shines a beam through the sample to a detector on the other side. The detector receives a thin slice of information about structures within the sample. The sample rotates so that over time, thousands of slices are collected.

Fourth, the specimen was reassessed to be sure it wasn’t damaged during scanning. Then they packed it up, retrieved another specimen, and started the whole process over again.

Ketcham said that for years, he and Kappelman and his students have compared CT scans of different kinds of monkeys to see if they could tell ones that were leaping from ones that were swinging from trees from ones that were walking on all fours.

“We always joked that we did this because some day Lucy would come through the door and we could scan her and compare her to the others,” Ketcham said. “It was just a joke because there was no chance that Lucy would ever be brought out of Ethiopia to get scanned. It was just impossible.” Well, now the impossible has happened.

by Marc Airhart

For more information about the Jackson School contact J.B. Bird at jbird@jsg.utexas.edu, 512-232-9623.