Edge of the Desert: Water Research Aims for Global Sustainability

January 10, 2008

Ian Duncan grew up on the edge of the desert. As a child in New South Wales, Australia, years would pass without rain, Duncan recalls. His family had to rely on artesian water—hot and salty groundwater—until rain would fall and collect in a tank on the roof of his family’s house. Growing up in this environment, Duncan gained an appreciation for water that would inspire his future career as an environmental scientist.

Now associate director for earth and environmental systems at the Jackson School of Geosciences’ Bureau of Economic Geology, Duncan maintains a global view of water resources from his office in Austin, Texas. He sums up future water challenges in one word: sustainability.

Duncan is part of a growing cadre of researchers at The University of Texas at Austin who focus on the science, technology, and policy that will ensure future water supplies. Water and water resource sustainability is a particular focus of the Jackson School, where most of the researchers work.

Bridget Scanlon, a senior scientist at the Jackson School’s Bureau of Economic Geology, works on agricultural water use and its relation to land use. With global population expected to grow from 6 billion to 9 billion by 2050, water demand is going to continue to grow, placing more strain on an already-stressed resource, Scanlon says.

Population growth is already leaving its water mark on Texas, points out David Maidment, director of the university’s Center for Research in Water Resources. When he moved to Texas in 1980, the population there was 14 million; it is now 24 million. “We added 10 million people on a fixed water resource, and inevitably we are slowly evolving to a greater degree of vulnerability to shortages in water supply,” Maidment says.

Fortunately for the university’s water researchers, Texas is at the forefront of studying the types of water challenges that plague communities worldwide, says J.P. Nicot, a research associate at the Bureau. A combination of factors makes it an ideal place to study water resources. Texas is a semi-arid region like much of the world’s population centers, and it has long-term hydrologic, agricultural, and other data to inform current studies of the water system. “There is no other state I know of that has so many models of their aquifers and such a good database for samples that would help you calibrate the models,” Nicot says.

| Touring Ancient

Aquifers Deep in the caves of Texas lies a valuable repository of water data. They chart the history of water pathways through ancient aquifers, offer a glimpse past climate changes, and help scientists monitor modern – day water resources |

Water is a resource so interconnected not only with earth systems but also with society that its management needs to be interdisciplinary, says Jay Banner, director of the university’s Environmental Science Institute and a professor at the Jackson School. Maidment, Scanlon, Duncan, Nicot, and Banner (see sidebar), along with Jackson School colleagues like Jack Sharp, current president of the Geological Society of America, all bring different areas of expertise to the table to address water sustainability in the coming decades. Their work forms an interdisciplinary framework for thinking about the growing water demand.

Water for Models

What Maidment fears most, he says, is a drought—not just any drought, but a “drought of record,” like the decade long drought Central Texas experienced from the late 1940s through the late 1950s. It is the drought by which scientists now measure all droughts in Texas, Duncan says. River levels dropped dramatically; streams dried up. “If ever that happened again here, the degree of concern and disruption to the life of Texas would be quite profound,” Maidment says.

Maidment has seen the effects of such a drought firsthand, not in 1950s Texas but halfway around the world in present-day Australia during a visit in November 2006. An extensive drought in Australia is causing nationwide despair, he says, with entire towns running out of water. Duncan’s mother lives in East Australia, where her town is down to just having a few percent of water in the reservoir.

Maidment also saw similar despair in Corpus Christi in 1984, when a major drought resulted in the city having only 300 days left of water supply. “So they faced the prospect that in 1985, the city of Corpus Christi would have no water and that caused a large panic which led to a loss of confidence in the leadership of the city and to a lack of confidence in the level of technical advice they were receiving,” Maidment says.

The city would recover, but seeing the effects of the drought on Corpus Christi gave Maidment a mission: to help make sure that a community’s citizenry is as informed as possible about its own water supply. For the past 20 years, he has been working toward that by building digital maps of Texas’ surface and groundwater resources. Surface water comes from streams, rivers, and lakes, while groundwater comes from underground natural reservoirs of water called aquifers.

In the late 1990s, the state’s leadership, including then Governor George W. Bush, started asking questions about the state’s water supply, basic questions, Maidment says, such as: How much water does Texas have? How much does the state need? Scientists and policymakers were not able to address these questions adequately, leading to the state senate passing legislation in 1997 that required that Texas digitize all its water maps and get a handle on water management.

That was when Maidment was able to step in with his geographic information systems (GIS) and hydrology expertise. He and Ralph Wurbs at Texas A&M University had been leading research for years on surface and groundwater mapping and modeling. Now, 10 years after the legislation passed, the GIS products are finally coming out—helping to tell policy-makers and citizens alike where their water resources are located and how much they have. “We now have water availability models, and a letter has been sent to every water permit holder in the state explaining how secure their water availability is in the event of a drought,” Maidment says.

But Maidment’s work is not stopping there. He is working with CUASHI (Consortium of Universities for the Advancement of Hydrologic Science), an NSF-funded organization of university researchers, to make water maps and models even more accessible to the public. He wants to expand on methods used elsewhere in the country to help Texas further manage its water resources, hoping to eventually have a water availability map as easy to use as Travelocity, for example, he says.

All of this work, Maidment says, will hopefully, at a minimum, mitigate the political and social ramifications of a drought. “What we owe to our citizens is that they should feel their universities and their state are on top of the problem and are conveying the magnitude of the issues.”

Water for Food

When Bridget Scanlon thinks of water, she thinks of food and how vital water is to the production of agricultural crops. She initially became interested in water because of her interest in helping to feed the poor of Africa. She has not made it to Africa yet, but she is making great strides in understanding the processes at work there through her research in Texas.

For Scanlon, agriculture is the elephant in the room when it comes to discussions of water demand: Globally, agriculture consumes 90 percent of freshwater resources. “We need to get a handle on the water used in food production in order to manage water resources effectively,” Scanlon says.

And Scanlon’s work has been aiming to do just that. She and her colleagues have been looking at the impacts of land use on water in the Texas High Plains, which is one of the largest agricultural areas in the United States. Her work covers a lot of ground, from looking at various agricultural practices to examining flow patterns in the High Plains aquifer, which covers parts of South Dakota, Nebraska, Wyoming, Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, New Mexico, and Texas.

Most recently, Scanlon published a paper in the journal Water Resources Research about the effects of converting natural rangeland to cropland. Some of what her research group found was surprising, for example that converting from grasslands to cropland actually increases how quickly groundwater can be replenished in the aquifer. Converting to agriculture in many parts of the world, including Australia and Africa, as well as Texas, has thus caused groundwater levels to rise. Scientists previously had not recognized such a positive benefit of agriculture, Scanlon says.

Perhaps the biggest consideration for agricultural practices, however, is irrigation. “Any type of irrigated agriculture is basically not sustainable,” she says. For example, even in the High Plains, where irrigated agriculture occupies only 11 percent of the land surface, it greatly depletes groundwater resources. From 1950 to 2003, the average groundwater level declined throughout the High Plains about 4 meters, and the average decline was as high as 12 meters in the Texas section of the High Plains. Irrigation is basically mining the resource, using it faster than it can be replenished.

Solving the problem of irrigation is complex, however, as deficit irrigation results in salinization of soil. When crops use water, they leave salts behind. With enough watering through irrigation, the salts get flushed out, but relying only on rainfall, the soils became inundated with salt.

The solution, Scanlon suggests, is rotating between rain-fed and irrigated agriculture, where “you let the water levels rise to a certain extent, then you have a period of irrigation, and then you move back to nonirrigated rain-fed agriculture.” Other options people are considering include rainwater harvesting and planting crops more in season with natural climate variability.

Despite these challenges, however, Scanlon remains optimistic. “For agricultural water management, there’s a lot we can do,” she says. “Even changing tillage, you can really change the water cycles in that system.” Scanlon continues to work toward understanding the various impacts people can have on agricultural water management, and hopes to eventually transfer what she has learned in Texas all the way to Africa.

Water for Energy

Agriculture accounts for more freshwater consumption than any other human activity—90 percent of all freshwater humans consume globally and 80 percent in the United States. Energy consumes less, because water used for energy is often returned to the water system, and yet energy is the largest withdrawer of freshwater in the United States, accounting for nearly half of all freshwater withdrawals.

“Every time we leave a light on in the room, we’re using electricity and that electricity uses water,” Duncan says. This less-publicized use of water is a major challenge to sustainability. The same population pressures that could push the water demand to extremes in the next 25 to 50 years will also create greater energy demands.

To better understand this important issue, Duncan has just received a grant from the Texas Water Development Board. He wants to find some more sustainable, viable options for electricity generation that use less water.

The majority of electricity in the United States comes from thermoelectric power. Power plants either burn coal or use uranium fission to boil water and make steam that turns a turbine and creates electricity. “We end up having to use water not just in the steam but also to condense the steam, and cool the steam down,” Duncan says. The lakes of water right next to power plants are the sources of water being tied up to cool the steam. Although much water is returned to the lakes after its use in the plants—hence not contributing to higher consumption numbers—that water is not being used for drinking or growing crops, Duncan says.

One alternative to this water-heavy process is to use air, not water, to cool the water being used as steam in the power plants, Duncan says. Using technology similar to what is found in a typical air conditioner, such a system could save large amounts of water—using 5 to 7 percent less water than traditional thermoelectric plants.

One problem with air-cooling is that it works better in cold, dry areas than warm, moist areas. Duncan thus is going to be calculating which parts of Texas would benefit from dry cooling and whether that could be implemented to free up water resources for other demands.

| Salt Water Goes Fresh

in El Paso

On Aug. 8th, 2007, the largest inland esalination plant in the world opened in El Paso, Texas. Although desalination will bring some relief to the water supply, it does pose a host of scientific challenges… |

Another solution involves desalination, says J.P. Nicot. San Antonio, El Paso and Lubbock are all moving toward desalinating slightly salty groundwater to address their rising water demands and dwindling freshwater supply (see sidebar). Ironically, Duncan says, desalination uses quite a lot of electric power, which of course uses more water. Such a route, he says, is likely not sustainable in the long term.

J.P. Nicot, however, says that one solution would be to collocate desalination plants with energy plants. That way, the water being used to cool the steam for thermoelectric power generation could then be desalinated and used for other purposes, such as drinking water and agriculture. Regions of the Middle East already employ such a technique—building power plants close to desalination plants so that the water can serve dual-use.

Water for Living

In addition to the many water demand challenges, including agricultural and energy consumption, society will continue to face challenges related to finding enough clean water. Particularly in developing countries, water quality is a bigger issue than water quantity, but the issues are intimately connected, says Jay Banner.

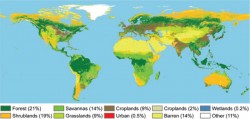

Society needs to be prepared to deal with water issues in an integrated way. “We’re going to need more crops to feed more people; we’re going to need more places for people to live; the cities will grow outward and continue to sprawl and change the way landscapes look and the way we use landscapes,” Banner says.

As scientists strive to understand the various impacts of the way people use water, they will continue to inform policy decisions from the local level on up. Banner is thus focusing on training the next generation of environmental scientists at the Jackson School—hoping to instill in them the interdisciplinary nature of the studies that Scanlon, Duncan, Nicot, Maidment, and others undertake. “In order to be able to solve these water problems, we can’t just do one type of water science,” he says. “We need to have as broad a perspective as possible.”

But it is not only scientists and policymakers who can make a difference when it comes to changing the global water picture. Changes in diet and personal practices can have dramatic impacts on water resources. Changing from a nonvegetarian diet to a vegetarian diet could save up to thousands of liters of water consumption per day per person, points out Scanlon, because of the quantities of water required for livestock. After changing agricultural practices, “the way that we could probably save the most water is through changing our individual habits,” says Duncan, such as turning off the faucet while brushing teeth, using low-flush toilets, and planting trees that use less water.

In Duncan’s mother’s drought-devastated Australia, people conserve water out of habit in small and large ways that may surprise Texans and others. “My mother does things like if she turns the hot water on and it’s cold initially, she puts a bucket under there and she collects all the water and she uses that for other purposes,” Duncan says. “There are a lot of things we can do as individuals to conserve water.”

By Lisa M. Pinsker

For more information about the Jackson School contact J.B. Bird at jbird@jsg.utexas.edu, 512-232-9623.