Barnett Boom Ignites Hunt for Unconventional Gas Resources

January 15, 2007

The global hunt for unconventional gas reserves recently turned to an unlikely spot—a patch of north central Texas that already seemed tapped out after 50 years of intense oil and gas drilling.

Technology, economics and one man’s persistence transformed the Barnett Shale formation of the Fort Worth Basin into a booming new frontier.

As conventional petroleum reserves dwindle in the U.S., public pressure mounts to reduce the country’s dependence on foreign energy, and the price of oil and gas rises, energy companies are setting their sights on “unconventional” domestic sources. These include oil sands, coal beds and shales.

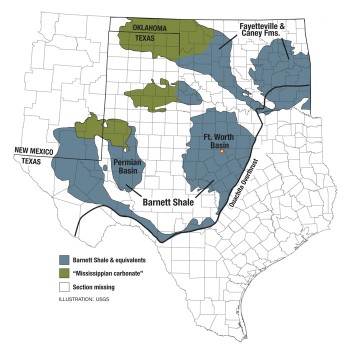

In less than a decade, the Barnett Shale play has become the largest natural gas play in the state of Texas and, as new wells sprout like bluebonnets across the Fort Worth region, it might soon become the largest in the nation.

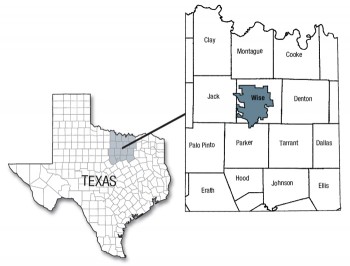

“This play already covers parts of 15 or more counties,” says Eric Potter, associate director of the Bureau of Economic Geology at the University of Texas at Austin. “It compares favorably with the biggest of the old oil booms of the early 20th century.”

Of course this boom is different. The concrete-like shale gives up its gas grudgingly. So individual wells tend to be smaller and more expensive to operate.

“The East Texas gushers would win out hands down,” says Potter. “But there are so many [Barnett] wells that even though they are modest, the total output is going to be huge.”

This play is also different because much of the untapped gas lies under the highly populated Fort Worth metropolitan area. Oil and gas companies are finding new challenges drilling in an urban setting.

Now, some experts are wondering if the boom can go global. The search is on for similar shale formations around the world, including the Fayetteville Shale in Arkansas.

Going to the Source

The fact that there is a Barnett boom at all reflects a tectonic shift in thinking. In the past, drillers bypassed the source rock that generated the oil and gas and focused on the reservoir rock, where the resources were easier to extract. Typically, oil or gas exits from the source rock and migrates to places where it is trapped. And those traps—conventional fields—typically do not cover a large area.

“There would be a field here and then a lot of blank space and then a few miles over there would be another field,” says Potter. “But this kind of play, it just covers county after county. You’re looking at thousands and thousands of wells covering the land.”

With new technologies for coaxing gas out of shales, drillers see the Barnett as both source and reservoir. One such technology is artificial fracturing—in which operators pump water and sand down a well to create fractures that liberate more gas from the rock.

Potter and his colleagues at the Bureau are analyzing the properties of shales across the state. Ultimately, they hope to apply their work to similar rock formations anywhere in the world.

“Now any kind of mudrock or shale that’s black, organic rich, reasonably thick, and reasonably deep we’re interested in,” says Potter. “The question is, all shales are not alike, so what makes a shale prospective as opposed to one that is not prospective? We don’t really know that yet.”

Wise Investment

Before he died in 2003, oilman and philanthropist John Jackson donated to The University of Texas at Austin royalty interests in roughly a thousand wells in the Fort Worth Basin, part of the bequest that led to the formation of the Jackson School of Geosciences. These wells were producing oil and gas from the younger Bend Conglomerate formation just above the Barnett.

The Bend Conglomerate was formed during the Pennsylvanian age, meaning it was laid down about 290 to 320 million years ago. The Barnett Shale, a marine basinal deposit of middle to late Mississippian age, was laid down about 320 to 360 million years ago.

Could the same wells produce significant amounts of gas from the older, deeper Barnett shale? Potter and his colleagues at the Bureau helped the University assess the long-term potential of the University’s royalty interests.

The University receives on average about two percent of the gross revenue from wells it holds royalty interests on. That money is being used to build one of the world’s premier geosciences programs at the new Jackson School. Because the money goes into general funds, it supports all of the activities of the school, including dean Eric Barron’s priorities: to create the world’s most student-centered earth science program, to attract and retain the best research talent, to increase the breadth and depth of the faculty and research community and to establish the “fabric of a great school.”

Researchers at the Bureau are providing technical analysis to help stimulate additional drilling and production in Wise County, where most of the University’s royalty interests are located. Emphasis so far has been on mapping the basic stratigraphic and structural framework, tracking successful drilling in the less developed southern part of the play, mapping similar conditions in Wise County, and remapping the thermal maturity of the formation. The maturity seems to relate directly to the gas to oil ratio, one of the key factors controlling gas flow rates.

According to Potter, the 5,500 wells currently pumping gas in the Barnett Shale play will ultimately generate on the order of $35 billion for their owners. As those companies pay taxes and wages, and as their employees and contractors in turn spend their money, there is an economic ripple effect, creating an overall value of about $100 billion to the Texas economy.

Of course, that is only counting current wells. Potter predicts that if gas prices stay relatively high, tens of thousands of new wells will be drilled in the coming decades.

“It’s a ubiquitous reservoir,” says Larry Brogdon, partner and chief geologist for Ft. Worth based Four Sevens Oil Company. “It’s everywhere. You can not drill a well without hitting the Barnett, and the gas is always there. The question is can you get it out or not.“

So far, operators have extracted 2 trillion cubic feet of gas from the Barnett Shale play. At about 1.5 billion cubic feet a day, that’s about 2 percent of the daily natural gas consumption of the U.S.

“When you can go from nothing to the second largest producing gas field in the country in a matter of just a few years, that makes a statement,” says Rich Pollastro, a geologist with the U.S. Geological Survey in Lakewood, Colorado. “That’s huge. And it could potentially become the largest producing field in the country. That was a real awakening for the country and now because of its success, industry and nations are looking at it worldwide.”

The Next Barnett?

In the summer of 2004, Southwestern Energy announced that the Fayetteville Shale formation in the Arkoma Basin had many of the same characteristics that made the Barnett Shale formation so desirable for gas production. Before the announcement, the company had quietly acquired mineral leases on nearly a half million acres of land.

The announcement set off another gas boom. Oil and gas operators familiar with the Barnett Shale rushed to Arkansas to get in on the action.

“The analog would be like a 19th century gold rush,” says Ed Ratchford, geology supervisor for the Arkansas Geological Commission in Little Rock. “Everyone stakes a claim. You don’t say this place is going to be better than this place. You don’t have time. People were leasing thousands of acres a day.”

Ratchford and his team maintain a well log library, a collection of well cuttings and cores from oil and gas wells across Arkansas. They used these to conduct geochemical tests on samples from the Fayetteville Shale and produce a regional picture of where good gas prospects were likely to be.

“We had companies all over us waiting for us to get this stuff done,” says Ratchford. “They were sitting out in the parking lot before we opened up. We were the only ones that had this information. It was critical for helping the operators know where to lease.”

In the excitement, many companies took a gamble on mineral leases.

“We had a lot of companies that had leased before the report came out,” says Ratchford. “Then they had a big golf ball in their throats saying, ‘I wish I hadn’t leased here.’ That’s the risk you run when you lease big tracts of land in a boom without having the luxury of doing the science first.”

“Some of those companies are going to make a lot of money,” notes Ratchford, “some are going to be doing tax write offs. That’s the nature of exploration. In a situation like this, where there’s a frenzy, there are going to be winners and losers.“

It’s too early to tell how much gas will ultimately be recoverable from the Fayetteville Shale. Southwestern Energy, still the largest lease holder in the play, estimates that they will recover 17 trillion cubic feet of gas.

The future looks good for the Fayetteville play. Ratchford expects the number of wells producing in the area to rise from the current 80 to a couple hundred and that gas will be extracted for at least 15 or 20 years.

He also notes that oilfield services provider Schlumberger has recently built a 30,000 square foot facility in Conway, Arkansas and will employ approximately 100 employees at that facility. “They would not do this if they didn’t believe this would be a long term venture,” says Ratchford.

Other areas that have generated interest for possible large shale gas plays are the Caney and Woodford formations in Oklahoma, the Floyd formation in the Black Warrior Basin of northwest Alabama, and the Barnett and Woodford formations in the Permian Basin of Texas.

It remains to be seen if the rising star of the Barnett Shale play will be eclipsed by other gas plays.

“The Barnett might be as good as it gets,” says Pollastro. “No one knows for sure.”

He produced the U.S. Geological Survey’s assessment of the Fort Worth Barnett shale play in 2003. At the time, he estimated that it held a remaining volume of 26 trillion cubic feet of recoverable unconventional gas. Now he’s evaluating the Barnett and Woodford formations in the Permian Basin, where drillers have experienced mixed results.

“It’s a different animal,” he says. “The Barnett in the Delaware Basin part of the Permian Basin is deeper and is more clay rich, so at present it’s not working like everybody thought it would. It’s not as rich in organic material as the Fort Worth Basin. I think there’s good potential, but I think there will be a steep learning curve.”

by Marc Airhart

Sidebar: Father of the Barnett

A unique set of factors converged to kick off the Barnett boom. New technologies such as artificial fracturing and horizontal drilling made it possible to extract large amounts of gas from shales. The relatively high price of gas in recent years made it economically viable.

Yet according to Eric Potter, neither of these would have mattered without one critical element:

“It wasn’t high tech. It was persistence and experimentation on the part of one company that got this boom going.”

Mitchell Energy had produced gas from a shallower formation, the same formation that John Jackson had discovered in the 1950s. That production was waning.

“They began looking around for what could be done in the same area,” says Potter. “They had always noticed that when you drilled through the Barnett, you would get a gas show. But everyone thought you wouldn’t get much gas.”

Even though shale may have a lot of pores with the ability to store gas, it is not very permeable. In other words, it does not have many connections between the pores and so trapped oil and gas can not flow easily.

“Mitchell Energy sunk a lot of money over a long period into learning how to stimulate the rock so it would flow,” says Potter. Their first attempts were expensive “massive hydraulic frac jobs.” They would pump a very large volume of fluid and sand down a well bore to crack the rock and give it more permeability. At first, they got the gas flowing, but the methods and materials were expensive. So they wondered if they could pump less fluid and get the same effect.

“They arrived at something called a light sand frac,” says Potter. “Suddenly it was economical and at the same time—in the mid-1990s—the price of gas was rising. By the late 1990s, they had perfected the technique in vertical wells and started applying it to several hundred wells. That’s when it came to the attention of industry.”

Potter first heard about these early successes from a Mitchell employee in 1996.

“I didn’t think it would have the kind of impact it did,” he says. “I wasn’t the only one. Most people in industry were surprised and had difficulty adjusting to the notion that shale could produce in commercial amounts over such a wide area. There were only a few companies that appreciated the value of hydraulic fracture technology applied on such a large scale.”

When thermally-mature organic-rich mudstone is drilled into, the pressure drops and gas is released by a process called desorption. Early estimates of how much gas would be given up by the Barnett Shale turned out to be far too low. The experiments were run again and it was realized that this shale would give up much more gas than was previously thought.

“Then it was realized, oh, if you scale that up to the whole area and then to the whole county and up to the whole Basin, the amounts of gas are really quite prodigious,” says Potter. “People became aware of that in 2002 and 2003 and that really got the ball rolling.”

Mitchell Energy already had critical infrastructure in place to process and transport gas. So they could quickly and economically take advantage of the discovery.

“It took George Mitchell 18 years to make it work,” notes Larry Brogdon, partner and chief geologist for Four Sevens Oil Company. “He is the father of the Barnett Shale. He was tenacious. He started in 1981 and it really didn’t take off until 1999. And even then, it took a long time to develop it.”

Sidebar: Won’t You Be My Neighbor?

“I’ve worked in Mississippi and Montana and all over Texas and some in the Middle East,” says Larry Brogdon, partner and chief geologist for Four Sevens Oil Company. “I never dreamed that the best gas play I’d get into was here in Fort Worth, right under my feet.”

To get the gas, operators are rushing to find suitable surface locations for drilling rigs, or “pad sites.” Thanks to horizontal drilling, pad sites can be almost anywhere including undeveloped areas near creeks, floodplains surrounding rivers, pastures, industrial corridors, and railroad and utility rights of way. From these spots, operators can drill horizontally underneath otherwise impractical areas such as subdivisions and business parks.

Brogdon, who graduated from The University of Texas at Austin in 1974 with a bachelor’s degree in geosciences, has had to become something of a diplomat.

“In this play, in the urban part, one of the most important things is the political aspect of what you’re doing,” he says. “I spent untold hours meeting with city councils and home owner associations, educating them about what we were doing and how we did it. Because most people had no clue. They were amazed how we could drill horizontal wells and what we could do. The more understanding they are of what we are doing, the easier they are to work with.”

Brogdon says it’s important to tell the land owners the truth:

“You say that no one is going to get rich. It is a commodity and the price goes up and down. We tell them that there’s going to be a well, but we don’t know how good the well is going to be. We tell them it’s like getting an annuity—money that’s coming to their mailbox that they never expected.”

Some residents, according to Brogdon, get $50 a month in the mail, while others get hundreds. He says overall, about 95 percent of the landowners he approaches eventually sign on to lease their mineral rights.

“Once you start getting an income stream for citizens, you turn adversaries into advocates,” says Brogdon.

Of course, that only benefits those homeowners who actually own their mineral rights. Many in the Fort Worth area do not.

Despite the diplomatic efforts of Brogdon and others, some local residents are not happy about all the urban drilling. They complain about the noise and appearance of drilling machinery, the possible decline in real estate values, and the potential for accidents close to homes, schools and businesses.

According to Brogdon, energy companies are using new technologies to make drilling quieter and they are landscaping around some drilling sites.

“All of this is something that operators are not used to and are learning to do,” says Brogdon. “They’re wiling to do it because the gas is there. If you’re willing to do it, you get the prize by getting the gas.”

Sidebar: A Super-Sized Thirst

To coax gas out of the concrete-like Barnett Shale, operators pump large amounts of water down their wells to fracture the rock. One horizontal well uses about 3 million gallons of water. Most of the water for these so-called “frac jobs” comes from groundwater.

According to the Texas Railroad Commission, in 2005, about 2.6 billion gallons (or 8,000 acre-feet) of water were used for frac jobs in the Barnett Shale. That represents 1.6 percent of the water pumped from the Trinity Aquifer for all human uses.

That might not seem like a large percentage. It is an average, though. In some areas, gas drilling might represent 10 or 20 percent of the local usage.

“On average for the aquifer, this is not a big deal,” says Jean-Philipe Nicot, a geological engineer at the Bureau of Economic Geology. “But for some heavily drilled areas like Denton County, it may be an issue. If that drilling expands elsewhere in the area it may become significant.”

If drillers have one vertical well every 40 acres, and if each corresponds to one water well nearby, water use is well distributed across the landscape. In the Barnett Shale, though, it’s typical to use horizontal drilling with multiple wells originating in a much smaller area. Pipelines are also used to deliver water from one spot to many wells.

“If you have one location heavily pumping water to hundreds of wells,” says Nicot, “then people in the vicinity would see an impact.”

In January 2007, Nicot and Potter released a report for the Texas Water Development Board estimating the water use for frac jobs in the Trinity Aquifer from 2007 through 2025. They noted uncertainties due to potential changes in the price of gas which might dampen or accelerate drilling and uncertainties due to new technologies or recycling techniques that might lower the amount of water used in each individual well. Under a mid-range scenario, the team projected a total groundwater use in that time period of 183,000 acre-feet (or 59.6 billion gallons or 226 million cubic meters).

About 80 new wells are drilled in the area each month. As the rush to capture more gas from the Barnett play intensifies, the amount of water used for frac jobs will likely rise. At some point, it could compete with water for drinking and farming. Neighbors with shallow water wells might see their supplies drop.

To complicate matters, the region has experienced a severe drought since the beginning of 2005. According to John Nielson-Gammon, Texas State Climatologist, this drought is one of the most severe the region has felt in the past century. “There’s been a shortage of hay and grass for cattle to graze, crop failures and reduced yields,” he says.

“We’re expecting a wetter than normal winter because of El Nino,” says Nielson Gammon. “But it’s going to take a lot more rain to make up for the deficits. I wouldn’t be surprised to see droughts continue next summer.”

The oil and gas industry might eventually be forced to use less water in artificial fracturing. Researchers at Texas A&M University are studying techniques for recycling used frac water.

Of course, concerns over water use would evaporate if the price of natural gas dropped to a point that made drilling uneconomical.