Some Dinosaurs Likely Cooed

October 11, 2016

Dinosaurs are often depicted in movies as roaring ferociously, but it is likely that some dinosaurs mumbled or cooed with closed mouths, according to a study published online in the journal Evolution in July 2016.

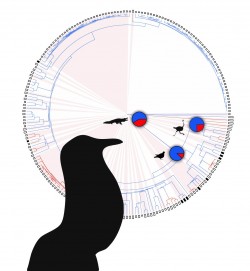

The research examines the evolution of a specialized way birds emit sound—closed-mouth vocalization. The study emerges from a new collaboration, funded by a grant from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, to understand the origin and evolution of the unique vocal organ of birds and the large array of sounds it can produce. Because birds descended from dinosaurs, the research may also shed light on how dinosaurs made sound.

Closed-mouth vocalizations are sounds that are emitted through the skin in the neck area while the beak is kept closed. The coos of doves are an example of this behavior. Birds making closed-mouth vocalizations usually do so only to attract mates or defend their territory. At other times, they emit sounds through an open mouth. To understand when and how closed-mouth vocalization evolved, researchers with the Jackson School of Geosciences, Midwestern University in Arizona, Memorial University of Newfoundland and the University of Utah used a statistical approach to analyze the distribution of this vocal ability among birds and other reptilian groups.

In total, the researchers identified that 52 out of 208 investigated bird

species use closed-mouth vocalization.

“Looking at the distribution of closed-mouth vocalization in birds that are alive today could tell us how dinosaurs vocalized,” said Chad Eliason, a postdoctoral researcher at the Jackson School and the study’s co-author.

Julia Clarke, a professor in the Jackson School’s Department of Geological Sciences, was also a co-author.

Back to the Newsletter