Law of the Sea: Institute Researcher Helps Map Arctic Seafloor

November 29, 2007

This past summer, a team of Russian explorers piloted two submersibles to the bottom of the Arctic Ocean at the North Pole and dropped a titanium Russian flag onto the seafloor. Although no other country has recognized Russia’s symbolic claim to the North Pole, it raises the question of who owns what below the Arctic Ocean, a region that might contain significant oil and gas reserves.

A few days later, an Arctic expedition headed by scientists from the University of New Hampshire’s Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping/Joint Hydrographic Center (CCOM/JHC) set out from Barrow, Alaska to map an area of Arctic seafloor called the Chukchi Cap. The goal was to collect data that could bolster U.S. claims to extend its Arctic maritime boundary.

“This is, in effect, a new cold war that is developing and Russia effectively fired the first shot in that cold war when they planted their flag beneath the North Pole,” said Fox News reporter Jonathan Hunt on a live broadcast in August 2007. “The U.S. is finally fighting back, with science for the moment—although that could change.”

Marcy Davis, a research scientist associate at the Institute for Geophysics in The University of Texas at Austin’s Jackson School of Geosciences who participated in the cruise, disputes the reported motivation.

“Our cruise was not a reaction to the flag planting event at all,” she said. “This is an ongoing project. It was the third mapping expedition to this part of the Arctic by this group since 2003 and they plan to return next summer.”

Davis was onboard the US Coast Guard Cutter HEALY, a polar-class icebreaker, to assist with bathymetry data collection during the month-long mapping expedition. The team included scientists and students from five academic institutions, the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration, National Ice Center, and the U.S. Department of State.

“This cruise provided me an excellent opportunity to learn more about bathymetric mapping and about the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea,” she said, referring to the international treaty that describes the process for extending sovereign rights over resources of the continental shelf.

The team found evidence that the foot of the continental slope—the area where the continental shelf meets the deep seafloor—is deeper and farther from Alaska’s coastline than previously thought. The location of the foot of the slope is one of several factors in establishing sovereign rights under the Law of the Sea treaty. But the U.S. is still in a data gathering phase and has not yet ratified the treaty, so any claims to an extended seafloor and additional resources may be some time off.

On the Other Foot

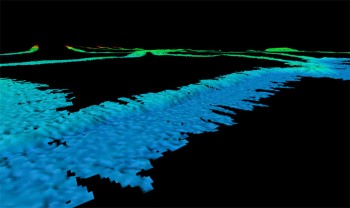

To create their maps, the scientists used a “multibeam bathymetry system”—an active sonar system which transmits a sound pulse, also called a “ping,” then listens for the pulse reflection or echo. The time from pulse transmission to echo reception is measured and then converted to seafloor depth using a formula based on the speed of sound in water.

The bathymetric maps they created are analogous to topographic maps of land surfaces, with depths below sea level replacing heights above sea level. The team also deployed ice beacons and buoys for the National Ice Center to collect long-term ice drift and weather data.

“One of the things that surprised us when we got out there was that our preconceived notion of the location of the foot of the slope was wrong,” said Larry Mayer, director of CCOM and leader of the expedition. According to Mayer, the continental shelf extends about 200 kilometers farther from Alaska’s north shore than once thought.

That doesn’t mean that American claims to the Arctic seafloor just automatically expanded by 200 kilometers. The Law of the Sea treaty has complicated rules involving more than just the edge of the continental shelf.

“I look at our job as to do the best science we can and present the best information about the areas we measure,” said Mayer. “I’ve always said there’s only one shape of the seafloor and that can’t be distorted. With the sonar we use, we get a full 3D picture. There’s no way to hide things.”

Mayer said it will be up to others to make policy decisions based on the data.

“The Law of the Sea has a lot of ambiguities and that’s where the lawyers and politicians will argue,” he said. “But they won’t argue over the morphological issues. The shape is the shape.”

To get a sense of the shape of the seafloor that Mayer, Davis and their colleagues discovered, climb into an imaginary underwater buggy and drive straight out from the shore of Alaska’s northernmost town, Barrow. You’d be driving on a long, gently sloping plateau called the Chukchi Cap. As you go deeper and deeper, sunlight fades away. Eventually, at a depth of around 2,500 meters, you see in your headlights a steep drop off. After roller-coastering down, you hit another gently sloping plain. Chug along for a while until, at a depth of about 3,800 meters, you come to an even steeper drop off. This is the edge of the continental shelf. As you careen down that step, you finally reach the relatively flat, deep seafloor. It’s this newly discovered second step that Mayer and his team believe is the real foot of the slope, or edge of the continental shelf.

Thin Ice

This past summer, Arctic sea ice shrank to its smallest coverage in at least a century. Some scientists said the most likely culprit is human-induced climate change. According to Mayer, the thinning made it easier for the HEALY to travel farther north than in previous missions.

“The state of the ice is good for mapping, but bad for the Arctic,” said Mayer, acknowledging the irony of climate change melting sea ice, potentially opening access to more fossil fuels, which in turn might fuel more climate change.

“This is where the government needs to step in and do something about it,” he said. “We shouldn’t stop mapping our oceans, but I think the government has a responsibility to make sure that any development that’s done is done in as responsible a way as possible.”

Davis said it was exciting to do research in the Arctic at a time of heightened media attention, but she was drawn there for other reasons.

“I love working in the Arctic because it’s all new territory,” she said. “Nobody knows anything—so it’s a lot of fun.”

Nations tend to cast a net into the sea and claim for themselves an area of seafloor that extends out a specific distance, currently 370 kilometers (200 nautical miles), plus possible extensions under the Law of the Sea, drawing an imaginary boundary that is perpendicular to the shoreline. Those nets often overlap for neighboring countries. Ironically, of the five countries bordering the Arctic Ocean, Russia and the U.S. are the only two that have actually negotiated the seafloor boundary separating each other. Denmark, Canada, Norway and Russia still have to sort out their common underwater borders.

“That’s the funny thing about trying to establish some conflict between the U.S. and Russia,” said Mayer, “that’s one of the few boundaries that’s been negotiated.”

While this might not be the start of a new cold war for the U.S. and Russia, governments and energy companies are keenly interested in the Arctic. The U.S. Geological Survey has begun evaluating how much undiscovered oil and gas might lie beneath Arctic waters. It plans to release its Circum-Arctic Oil and Gas Resource Appraisal in the summer of 2008. Meanwhile, despite Russia’s headline-grabbing feats and media hype, the debate continues about who owns what on the Arctic seafloor.

“Look, this isn’t the 15th century,” Canada’s foreign affairs minister Peter MacKay told a CTV co-host in August. “You can’t go around the world and just plant flags and say, ‘We’re claiming this territory.’”

by Marc Airhart

Also See: UNH-NOAA Ocean Mapping Expedition Yields New Insights into Arctic Depths