Decline in Aerosols Could Lead to More Heatwaves in Populated Areas

July 16, 2025

Heatwaves are becoming more frequent around the world. And while rising temperatures caused by greenhouse gas emissions are part of the problem, the declining levels of aerosols — the small particles that make up smog and air pollution — may be driving the rise even more, particularly in populated areas.

This finding comes from a study published in Environmental Research Letters and led by researchers at The University of Texas at Austin. While recent research has linked declining aerosols to rising regional temperatures, this study is the first to examine aerosols’ impact on people’s exposure to heatwaves.

“We knew that aerosol emissions were suppressing global warming at the regional level, but the impact of that same suppression on heatwaves near urban centers was much greater than we expected,” said study co-author Cameron Cummins. “So, as cities seek to curb their aerosol emissions to improve public health, they will also likely experience more heatwaves.”

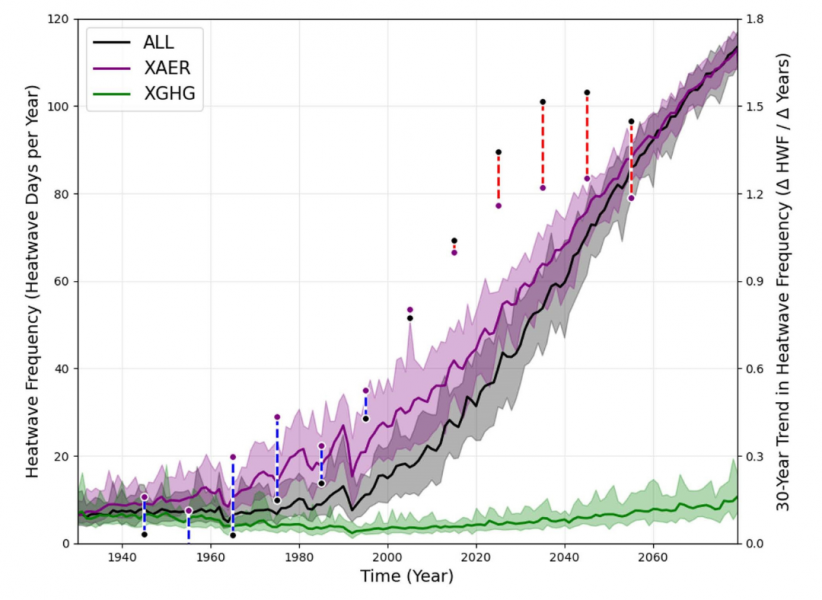

Using global climate models, the researchers found that aerosols are up to 2.5 times more influential than greenhouse gases at driving changes in heatwave occurrence in populated areas – with higher levels of aerosols suppressing heatwave exposure by reflecting the sun’s rays.

The research was led by Geeta Persad, an assistant professor at the UT Jackson School of Geosciences.

Cummins co-authored the study while earning a master’s degree from the school and first started analyzing data for the project as an undergraduate research assistant in Persad’s lab.

The researchers found that from 1920 to the present, higher aerosol levels helped suppress the occurrence of heatwaves in populated areas by about half. However, this trend is now reversing due to declining aerosol levels. The decline is due in part to clean air policies, which have been passed by countries because of the negative health and environmental effects of aerosols.

Populated areas, which release the most aerosols, are particularly at risk for accelerating heatwaves driven by aerosol decline in the near future, Persad said.

“Aerosols are really good at counteracting exposure [to heatwaves] right now, but that could rapidly change in the future,” she said. “We seem to have already crossed a tipping point where declining aerosols are accelerating heatwave exposure in a lot of places.”

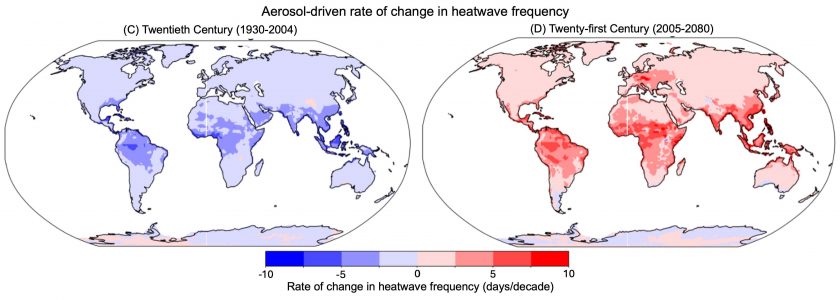

If global aerosol emissions continue to decline as expected in the coming decades, heatwaves are expected to go from today’s global average of about 40 days per year to an average of about 110 days per year by 2080. The regions that are projected to be hit particularly hard by heatwaves caused by declining aerosols include Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, South America and Western Europe.

In this study, a heatwave is defined as three or more consecutive days during a region’s warm season that exceed a 90th percentile temperature threshold.

Aerosols are often produced at the same time as greenhouse gases, when fuel or other materials are burned. However, the two behave differently in the atmosphere. Greenhouse gases raise temperatures, distribute relatively evenly around the world, and can persist from a few years to hundreds of years. Aerosols have a cooling effect, have a more regional distribution, and are often gone in a matter of weeks.

The regional distribution of aerosols and their lack of staying power is important, Persad said. It means that when countries reduce aerosol emissions, their impacts are evident often in a matter of years. That is a good thing when it comes to health and environmental benefits associated with aerosol reduction. However, the modeling results show that it makes populated areas particularly vulnerable to heatwaves as aerosol emissions decline.

Western Europe is a notable example. During the late 20th century, aerosols almost completely counteracted greenhouse gases’ impact, keeping Western Europe from experiencing many heatwaves. However, over the next 25 years declining aerosols alone could increase heatwave frequency in parts of Western Europe by 40 days per year or more.

The study results shouldn’t be taken as a license to pollute, Persad said. High aerosol levels take a direct toll on human health by harming the heart and lungs, which can contribute to disease and lead to premature death. Instead, the study’s findings should be a signal for cities to prepare for a world with more heatwave risk.

“This work suggests that what happens with aerosols in the near future is going to be really important for what happens with heat wave hazard and exposure and risk in the near future, the next 20 to 30 years,” Persad said.

The research was funded by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the National Science Foundation. The study was also co-authored by Jane Baldwin, an assistant professor at the University of California Irvine.

For more information, contact: Anton Caputo, Jackson School of Geosciences, 210-602-2085; Monica Kortsha, Jackson School of Geosciences, 512-471-2241; Constantino Panagopulos, University of Texas Institute for Geophysics, 512-574-7376; Julia Sames, Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, 210-415-9556.