Searching for Our Ocean’s Climate Past

Nobody Does Science Alone: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Logistics

Isaac Newton invented calculus and discovered gravity while hanging out at his mom’s house in 1666. These days it’s a bit harder to have a major impact on science while working alone. This fact was reinforced for me during a seismic survey cruise this summer in the Gulf of Mexico on which I was chief scientist, in which dozens of people from multiple countries all worked together to achieve the objectives of the expedition.

The work was planned to determine the age and thickness of sediment drifts along the Campeche Bank in the southeastern Gulf of Mexico, along the edge of the Yucatan Platform. This is where warm, salty surface water enters the Gulf from the Caribbean and forms the Loop Current. The Loop Current flows north into the Gulf before swinging east and then back south, forming a big loop (hence the name) and flowing south along the edge of Florida and then out through the Florida Straits, where it forms the Florida Current and then the famous Gulf Stream, which is so important to North American and European climate and North Atlantic Deep Water Formation (and thus global climate).

The Loop Current itself is important for the climate of the Gulf: sometimes the loop pinches off and forms a warm core eddy, which drifts across the western Gulf of Mexico disrupting fisheries, stressing offshore infrastructure, and providing a massive source of heat for tropical cyclones (the rapid intensification of both Katrina and Harvey right before landfall was due to those storms passing over a warm core eddy). In short, the Loop Current is Important. But surprisingly, we have a very poor understanding of its history before the era of direct observations.

We don’t know when it first formed, or whether it was stronger or weaker during past warm climates, which means we don’t know whether it will be stronger or weaker in the near future as the climate warms. A slower Loop Current would mean less poleward heat transport globally and more eddies (and thus more disruption of fisheries and infrastructure, and more hurricane fuel) in the Gulf of Mexico.

A 2009 cruise of the German research ship Meteor discovered sediment drifts on the edge of the Campeche Bank at a depth attributable to the Yucatan Current, the deeper countercurrent to the Loop Current. Sediment drifts mean there is a physical sedimentary archive of current flow here, and if we can figure out for how long those drifts have been deposited then we can figure out how long the modern current regime has been operating. Then, if we take sediment cores from those drifts, we can use proxies based on planktic foraminifera to reconstruct the strength of the Loop Current over time.

A 2009 cruise of the German research ship Meteor discovered sediment drifts on the edge of the Campeche Bank at a depth attributable to the Yucatan Current, the deeper countercurrent to the Loop Current. Sediment drifts mean there is a physical sedimentary archive of current flow here, and if we can figure out for how long those drifts have been deposited then we can figure out how long the modern current regime has been operating. Then, if we take sediment cores from those drifts, we can use proxies based on planktic foraminifera to reconstruct the strength of the Loop Current over time.

So, in 2018 Jamie Austin and I wrote a proposal to the National Science Foundation (NSF) to go do that with the support of scientists and colleagues from Germany and Mexico, and it was… rejected. We’re trying to do too much they said. So in 2019 we rewrote the proposal to focus on just collecting seismic data to determine the thickness and age of the drifts, and that time it was… accepted! Hooray.

So then we got on a ship and collected the data. Ha ha, just kidding. Writing a proposal and getting it funded is the easy part. To actually carry out a research cruise a whole lot of people have to manage a whole lot of things. As Principal Investigator, it’s very humbling to watch a whole bunch of people work to turn your idea into reality (also, to be clear, this wasn’t “my idea” so much a group project that I organized). The sediment drifts are in Mexican waters, and from the start we’ve been working closely with Mexican scientists from the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM, in the Spanish acronym). These scientists, Ligia Perez Cruz and Jaime Urrutia Fucugauchi, managed to get us ship time on UNAM’s Gulf of Mexico research ship, the B/O Justo Sierra. In order to get permission to conduct a seismic survey in Mexican waters, Jaime and Ligia had to do a tremendous amount preparatory work, meeting with government officials and the Mexican Navy to share survey plans and explain what we were planning to do. They also organized all the logistics for the cruise (port calls, scheduling, etc.) and put us in contact with trusted port agents in multiple ports. It is literally impossible to undersell how essential they were to making this cruise happen.

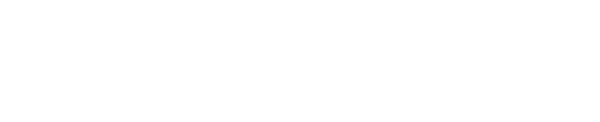

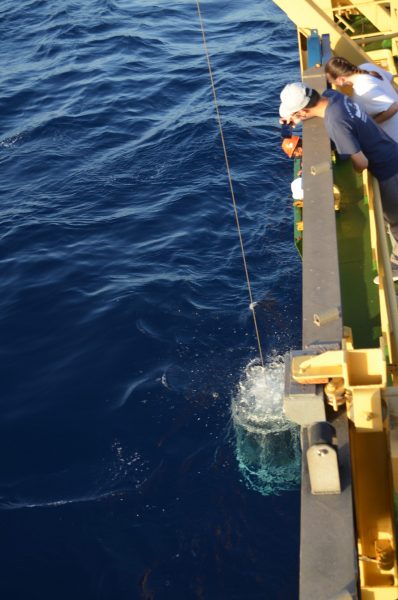

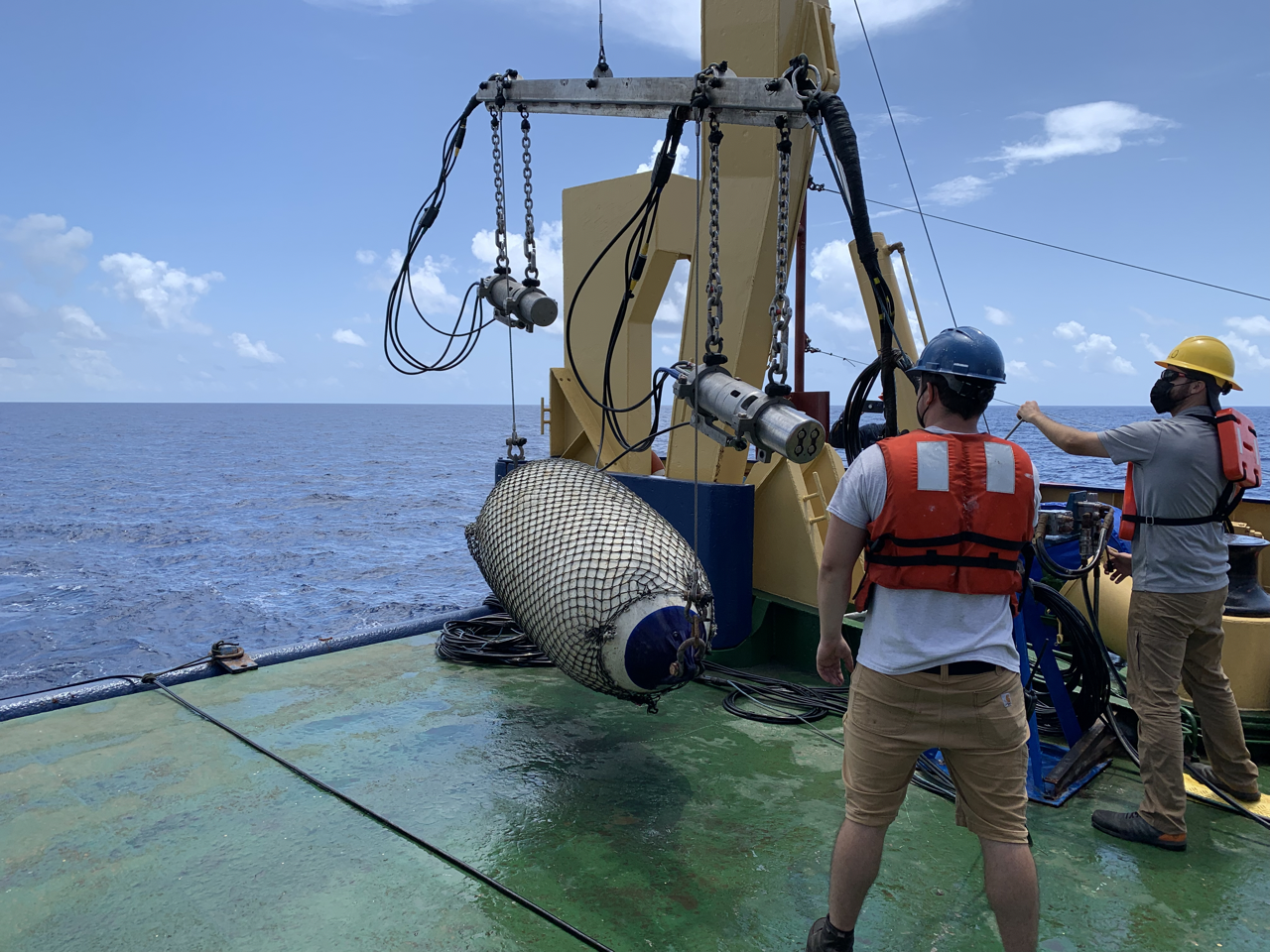

The seismic equipment (air guns, streamer, birds, GPS, topside hardware and software) was provided by NSF through Scripps Institute of Oceanography, who run a portable multichannel seismic facility. Scripps sent four technicians to set up and run the equipment on the ship. What they (and the ship) don’t have are air compressors, and you need compressed air to run air guns, so Scripps subcontracted with a company in Houston that provides portable compressors and hired a compressor tech from a different company to go to sea with us and fix them when they inevitably break. The folks from Scripps spent months going back and forth with shipping agents and port agents managing the complicated logistics and mountains of paperwork to get the equipment through Mexican customs and down to the ship. Then, they flew down and met the ship in Tuxpan and spent 3 days loading the gear and getting everything ready for the cruise. The Justo Sierra doesn’t have a bolt pattern on deck to simply bolt heavy equipment down, so they had to hire a welder to come and weld everything to the deck (and then come back, cut it off and grind down the deck when we got back).

All seismic work funded by NSF is required to follow National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) guidelines for acoustic disturbance in the water, so NSF had a contractor write up a 134-page environmental analysis summarizing the protected species (i.e., marine mammals and turtles) that were likely to occur in our area, the harm that might be caused to them by us shooting air guns for a week (very little, fortunately), and the mitigation measures we would need to take. This was then submitted to NMFS for review, posted in the Federal Register for public comment, and finally approved and sent to us a week before we left port.

One of the primary mitigation actions we were required to take was to bring protected species observers (PSOs) to keep a visual watch for any protected species and report any that entered an exclusion zone around the ship, which would require us to shut down the guns. So, we brought three PSOs with us from another contractor. From the minute we left port they kept a continuous watch during daylight hours (we saw plenty of dolphins, a handful of sea turtles, and no whales. Also, no shutdowns for species entering the exclusion zone).

Then of course there was a whole ship that we used to conduct the survey. The Justo Sierra has a captain and crew to keep the ship operational, to expertly steer the planned survey lines while maintaining course and speed through some pretty strong currents, to run the winches and cranes to deploy equipment, to cook food, and do all the other things that make a ship work (a brief sidebar about the food: it was the best I’ve ever had on a ship). That ship had never conducted a seismic survey in its nearly 50 years of service, but the crew were quick to learn and very accommodating when we had to change plans as circumstances evolved.

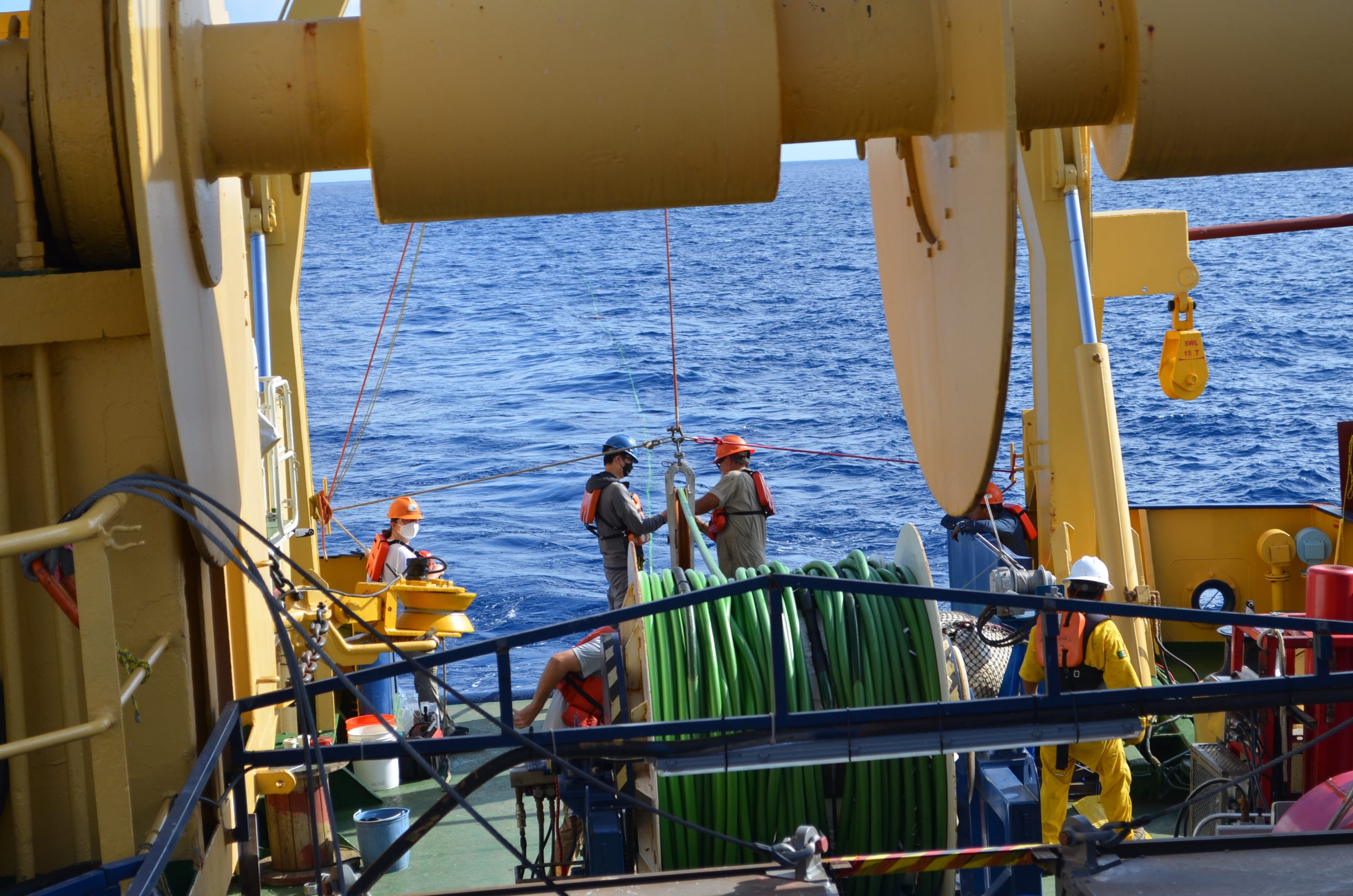

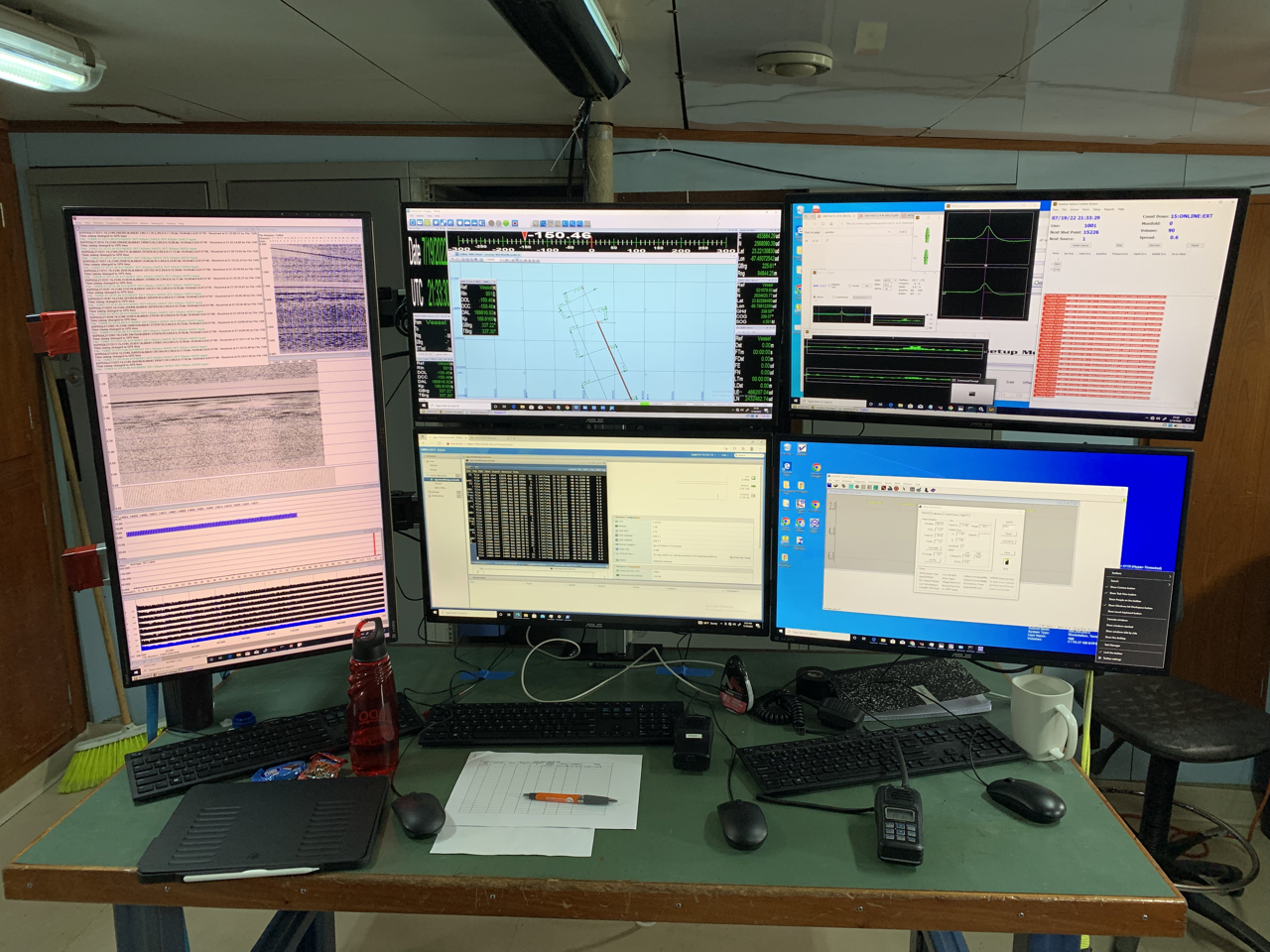

Finally, there were a lot of scientists on board to serve as watchstanders to help monitor the data as it came in and conduct preliminary processing. Ligia and Jaime brought two students from UNAM, and from UT there was graduate student Patty Standring, postdoc Jingxuan Wei, Jamie Austin, and me.

All told, that’s 15 officers and crew on the ship and 18 science party members from three universities and two companies at sea, not counting all the shore based people who helped with logistics, or protected species permitting, or travel. Someone whose name I will never know drove special lithium-ion batteries for the streamer birds all the way from the customs station in Monterrey to the Yucatan so they’d arrive at the ship in time. This is a lot of people investing a lot of time and money in carrying out an idea. Thankfully, all this paid off in some spectacular data that we are currently working to turn into a new proposal for a coring cruise and a workshop for an eventual scientific ocean drilling expedition (which would be an order of magnitude up the people and logistics complication ladder).

When this is all written up in a journal article or two, these vital contributions will all be condensed down to a few sentences in the Acknowledgements section. If we are very lucky and this research gets picked up in the news media, all the logistical work probably won’t be mentioned at all. But none of this would be possible without all those people’s work. So, shout out to everyone who helped: we literally couldn’t have done it without you.

Chris Lowery,

Research Associate

The University of Texas at Austin

Web Privacy | Web Accessibility Policy | Adobe Reader