Ancient Cave Cats of Texas

What kind of wildcats lived in prehistoric Texas? Rare feline fossils are taking UT scientists deep underground in search of answers.

By Monica Kortsha, Winter Prosapio and John Morretti

Located just north of San Antonio, Natural Bridge Caverns is one of the most popular tourist destinations in Central Texas. Each year, over 250,000 visitors venture underground to marvel at its massive chambers and dramatically lit formations.

But there is more to Natural Bridge Caverns than what is open to the public. The caverns are the largest in the state by volume, with most of that area being “wild cave.”

In the undeveloped dark, there are still discoveries being made.

Last year, while exploring the cave, the caverns’ co-owner and CEO Brad Wuest found fossilized bones from a small wildcat that potentially lived thousands of years ago. The bones, which were from a feline about the size of a large house cat, were located at the bottom of an 80-foot drop in a chamber called The Dungeon.

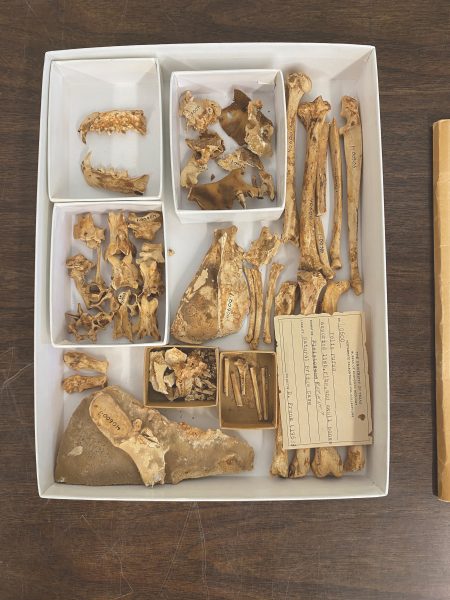

Wildcat bones are rare in the fossil record. But it wasn’t the first time they had been found in The Dungeon. In 1963, caver Orion Knox, who was among the first to explore Natural Bridge Caverns, found a selection of small wildcat bones in the same chamber. These bones were retrieved by Rueben “Bud” Frank, then a geology graduate student at The University of Texas at Austin, and brought back to the vertebrate paleontology collections at UT for safe keeping.

But it looked to Wuest that Frank may have left some bones behind in the cave.

Wuest called John Moretti, a doctoral student and paleontologist at the Jackson School of Geosciences, to tell him about the discovery — and to see if he was interested in picking up where Frank had left off decades before.

Moretti had questions: Did the bones actually belong to the incomplete wildcat in the UT collections? What kind of cat was it, and when did it live? And how did it end up in the darkness of The Dungeon, almost a mile underground?

He accepted the mission to retrieve the bones and began the search for answers.

Little did he know that there would be even more cats to come.

Cryptic Cats

Moretti studies how animal communities have changed over the past couple million years — a geologic time interval known as the Quaternary Period that ranges from about 2.5 million years ago to today.

Although past wildlife surveys have documented a diverse array of small wildcats that are now rare or absent in the state, such as jaguarundis, ocelots and margays, the feline fossil record of Texas is woefully sparse.

Not counting bobcats, there are just 10 wildcat specimens from five sites in the state, with six of those specimens from a single site — Schulze Cave in Edwards County. Count bobcats and you get just 20 more cats. Most of these wildcat specimens are represented by lone bones and fragments, according to Moretti.

Wuest’s discovery offered a much more complete look — consisting of multiple bones from different parts of the body.

“This material from Natural Bridge is really exciting because it’s way more than just a single jaw or isolated tooth,” Moretti said. “We have more material to deal with.

There’s more morphological evidence available, and therefore, more potential to observe traits that may be diagnostic or distinctive.”

The fact that the cat remains had been preserved in a cave — a natural climate-controlled environment — also raised the possibility they could contain something the other bones did not: pristine traces of ancient DNA.

Jackson School. The fossils were recovered by a geology graduate student in 1963 from a chamber called The Dungeon. Photo: Winter Prosapio/ Natural Bridge Caverns

DNA could provide a new avenue for determining what species of wildcat lurked in the caverns perhaps thousands of years ago. That’s important, Moretti said, because it’s difficult to determine what species a wildcat belongs to based on bones alone.

Over the years, the small wildcat remains from The Dungeon in the UT collections has been tentatively classified by different people as a number of different felines. The potential contenders include a bobcat, margay, an extinct species known as a river cat, and jaguarundi.

The wobbly identity is in part due to anatomical similarities shared by small wildcat skeletons across species, Moretti said. But another issue is that there aren’t very many wildcat bones available for comparison in the first place.

The newly discovered bones and potential DNA could give scientists the clues they needed to sort out the identity of the ancient cave cat — which in turn, could aid in further identification efforts.

“Once we have a partial skeleton, not just isolated bones, we can analyze the utility of traits that have been used in the literature [to identify small wildcats],” Moretti said. “That may help refine our ability to identify these animals, period, in any context.”

But Moretti would need some help determining if ancient feline DNA was there in the first place. That’s where David Ledesma, a doctoral student specializing in ancient DNA extraction, came in.

Ledesma works closely with paleobiologist Melissa Kemp, an assistant professor in the UT College of Natural Sciences who specializes in using ancient DNA fragments to identify reptile and amphibian fossils from cave samples. He said a wildcat offered an exciting new opportunity.

“I usually extract DNA from much, much smaller fossils,” said Ledesma, who earned his undergraduate degree from the Jackson School. “When I first heard about [the wildcat], I was interested in helping out.”

Before that could happen, Moretti had to bring back the bones. As he underwent specialized training to safely navigate the cave, a Natural Bridge Caverns team continued to explore and make amazing feline finds.

Meanwhile, More Cats

It started with pawprints. In March 2022, the team discovered the cat tracks pressed into the muck of a passageway near the drop into The Dungeon. Four days later, they found the remains of another small wildcat.

This specimen was nearly complete, with the bones scattered in a large chamber called The Inferno Room. The chamber is accessed via a 60-foot drop in an overlying passageway. Near the drop, the team found even more wildcat tracks.

The pawprints in the passageways preserved something rare in the fossil record: a sense of what an animal was feeling. The tracks eerily conveyed the discomfort of being in the total darkness of the cave. They showed a cat covering the same ground over and over, and attempting to climb up the wall before sliding back down, claws dragging.

Together, the skeletons and tracks seemed to tell a compelling story of two small wildcats deep within the cave, walking through the darkness, perhaps disoriented, slipping down different drops until they fell to their deaths in The Inferno Room and The Dungeon.

The narrative was instantly appealing, but Moretti was cautious about jumping to conclusions. It would take more research to match the tracks to foot bones from the cave cats below. But that didn’t stop him from being astounded by what the expedition team was finding.

“One ancient small wildcat skeleton was, alone, remarkable,” Moretti said. “Two skeletons, close together and seemingly associated with a trackway — that was unheard of.”

That was before the third wildcat skeleton.

This cat was found much closer to the entrance in a passageway known as Discovery Crawl. Based on the age of other bones previously found in the passageway, including now regionally extinct black bears, this feline met its end maybe a century or so ago — much more recently than the other two cave cats found deep underground.

By January 2023, everything was in order to recover the fossils. A specialized wildcat expedition team had come together to assist Moretti and document the mission. The team included Natural Bridge Caverns co- owners and brothers Brad and Travis Wuest, John Young, a paramedic with experience in cave rescue, and Chris Higgins, a world-renowned cave photographer.

All that was left to do was to go get those cats.

Back Together Again

It took three days to carefully chart, pack and transport the fossils from deep within the cave. But by the end of the third day, the two cats were back at the surface again, perhaps for the first time in millennia, and safely settled into a drawer in the UT collections. A couple weeks later, they were joined by the third cat from Discovery Crawl.

One of the first things Moretti did after retrieving the fossils was to compare the bones he recovered from The Dungeon with those collected from the chamber 60 years ago. It was no question that they had come from the same cat. A number of the bones in the collection fit right back into slabs of flowstone surrounding many of the recently retrieved fossils.

“It’s very clear that what we collected this year and what they collected in 1963 was one individual skeleton clustered together,” Moretti said.

It looked like Frank, the UT graduate student, had focused on bringing back the most accessible fossils, ones that could be pried from the rock without breaking. The rest were left behind for Wuest to find six decades later.

In the long run, that may have been for the best. Ancient DNA extraction and sequencing technology didn’t exist when the first batch of bones were brought back from The Dungeon. Now, Moretti and Ledesma could start the process right on campus.

After a couple weeks of workup, they had promising results. All three specimens retrieved by Moretti contained DNA fragments consistent with ancient DNA. There are still a few more hoops to go through. The DNA has to be confirmed as feline, and not some other cave interloper or human contaminant. If it’s consistent with a cat, it will then be sent off for sequencing and species identification at an off-campus lab.

In the meantime, Moretti is keeping his distance from the fossils. Proximity can lead to bias when it comes to species identification, and he doesn’t want a potential hunch to undermine the scientific method he is developing to analyze the bones.

The method involves creating a species score-card of sorts that will allow him to systematically compare anatomical traits from each of the three cave cats to those from dozens of possible cat species contenders.

If a cave cat has a lot of traits in common with a particular species, it’s probably a match.

Moretti has already had success carrying out this type of analysis. In 2022, he determined that an avian ankle bone from an archeological site in New Mexico belonged to a thick-billed parrot. In that case, he only had a single bone. The new nearly complete wildcat specimens offer much more to work with. If successful, the ancient DNA analysis can help ground-truth his results, too.

Moretti also hasn’t forgotten about the muddy pawprints pressed into the passageway. He is collaborating with a LiDAR company on a portable system that can scan them so the exact dimensions can be compared with the foot bones from the cats. If it’s a match, the mystery of how the ancient wildcats of Natural Bridge Caverns met their end could be solved.

Although Moretti is closing in on answers, the identity of the cats and the details of their death remain, for now, shrouded in mystery. For Moretti, he said that the journey of exploration comes with its own rewards.

“I’ve had to learn about ancient DNA. I’ve had to learn about LiDAR. I’ve had to learn about these different aspects,” he said. “And it’s great because it means the research is more interesting and more strongly supported. But it also means I know how to do more things too, and I can apply that to the next project and keep building those skills and learning more.”

And who knows what else is waiting to be found in the depths of Natural Bridge Caverns?

The University of Texas at Austin

Web Privacy | Web Accessibility Policy | Adobe Reader