The Geosciences Advantage

JACKSON SCHOOL OF GEOSCIENCES ALUMNI ARE FINDING OPPORTUNITIES AND CLIMBING CAREER LADDERS IN FIELDS AND SETTINGS THAT MAY SURPRISE YOU

By Anton Caputo

When most people think of the geosciences, they think of oil and gas, and with good reason. The ties between the industry and the science are long and proud. But the truth is that a top geosciences education prepares students for much more than a career in a single industry. And with most of the major challenges facing modern society having geosciences at their core, employers are beginning to wake up to the reality that geoscientists can be valuable assets.

From climate change and the energy transition to finding sustainable supplies of clean water and dealing with hurricanes, earthquakes and floods — geoscientists have expertise that no other discipline can offer. Add to the mix the fact that modern geoscientists are trained to handle massive data sets and high-tech tools, and the education becomes a foundation for a wide variety of potential career opportunities. Following are some great examples of Jackson School of Geosciences alumni who have used their hard-earned degrees and expertise to forge career paths that might not seem obvious at first glance. Finance, insurance and software are just a few of the examples.

Climate Translator

Kelly Hereid, Ph.D. '12

Businesses and industries all over the world have begun coming to grips with a new reality: Climate change is going to affect their bottom line in any number of ways, and in many cases, they don’t have the tools or the expertise to figure out how.

That’s where someone like self- described “climate translator” Kelly Hereid comes in.

Hereid, who graduated with a doctorate from the Jackson School of Geosciences in 2012, is the director of catastrophe research and development at Liberty Mutual Insurance. It’s a profession that a geosciences education is perfectly suited for, Hereid said, a fact that businesses were just recognizing when she entered nearly a decade ago.

“Now they very heavily recruit climate scientists because they have come to realize this is an important part of their risk management strategy,” she said.

Hereid started her career in reinsurance, which is the industry that handles the biggest disasters by spreading risk among insurance companies. As a doctoral student at the Jackson School, she had no inkling of what her future had in store. Hereid did paleoclimate work on ancient coral to determine how El Niño and La Niña were affected by past climate and how the weather patterns might react to future climate change.

Hereid thought that academia may well be in her future. But after shopping her CV at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union, she was seemingly randomly contacted by someone in the industry asking whether she was interested in reinsurance. That sent Hereid scrambling to Google to figure out what exactly reinsurance was. Once she did, everything changed. Hereid quickly realized it was one of the first sectors that would be affected by climate change.

“It is really an area where the rubber meets the road with climate impacts and climate adaptations,” she said. “The kind of risk management decisions that happen in the insurance or reinsurance industry fundamentally shape how our society will experience climate impacts from hurricanes and wildfires and floods.”

She started her career with Chubb Insurance, the world’s largest publicly traded property and casualty insurance company, where she served as an analyst before working her way up to senior research scientist and assistant vice president.

When she began, the industry was struggling to figure out how climate change might increase the frequency and strength of hurricanes, storm surge, flooding and a host of other variables that could make a disaster even more dangerous and monumentally more expensive. And she found that people throughout the business world were talking about climate risks, but lacked a toolkit to assess the strengths and weaknesses of climate models when applied to business problems.

Her job involves breaking down and reassembling catastrophe models, the tools that insurers and reinsurers use to manage the biggest and most severe disasters, and helping her colleagues understand how they should make business decisions based on the tools. These tools can help determine, for instance, how damaging a megadisaster like Hurricane Andrew would be if it were to hit again today.

Hereid, who is on the Jackson School’s Geology Advisory Council, is tireless in her outreach to students about the relevance of a geosciences degree to modern business. Her No. 1 tip for those looking to break in is to learn how to succinctly communicate complex scientific topics to a diverse audience.

“I came in with a broad geoscience education where I can say something coherent about earthquakes, volcanoes, sea levels and hurricanes or whatever because I have some fundamental understanding of how the Earth’s systems work,” she said. “That really gave me a leg up.”

The results, she said, can be quite fulfilling.

“I think just opening people’s eyes to seeing that there is something you can do with geosciences that will legitimately help us adapt to climate change, that’s what gets me out of bed in the morning,” she said.

Coastal Protector

Kelly Brooks, B.S. '09

Growing up in South Texas, Kelly Brooks fell in love with the Texas coast, visiting often to surf, fish or just hang out with her family. So it’s sort of poetic that years later, she is using her geoscience expertise to protect that same coastline.

Brooks, who earned a bachelor’s degree from the Jackson School of Geosciences in 2009, is a project manager in the Texas General Land Office’s Coastal Resources Division. In that role, she works with coastal communities, nonprofits and state and federal agencies to nourish beaches, restore and protect habitat, and generally protect the state’s critically eroding coast.

She traces many of the skills she uses on a daily basis to her days at the Jackson School and fondly recounts being a “guinea pig” in the inaugural Marine Geology and Geophysics field course in 2008.

“I learned about geophysics, data collection and data processing and interpretation, really the full gamut,” she said.

In addition, Brooks also learned how to design and plan her own surveys, a combination of skills that comes in handy for her current role, particularly when designing surveys for the new Texas General Land Office (GLO) initiative to map sediment and develop a sediment management plan for coastal projects.

“If you have those technical skills, it really helps the agency develop projects that are a more effective and efficient use of state funds,” she said.

For instance, because of her geophysics knowledge, she can help the agency’s Energy Resources Division with seismic permitting.

Brooks didn’t go directly into coastal protection. After finishing a master’s at Texas A&M University focused on geophysical oceanography, she took a position at Berger Geosciences in Houston, where she did third-party assessments of shallow hazards in the Gulf of Mexico — a burgeoning field in the wake of the Deepwater Horizon disaster. But she was itching to move back to Austin to be closer to family, so she decided to look at state agencies. That was her introduction to the GLO.

“When I realized that we had a state agency that was dedicated to coastal resources, that really spoke to me,” she said.

In some ways, Brooks has gone full circle to her undergraduate Jackson School days. She now works with the Bureau of Economic Geology on coastal LiDAR surveys and with the Institute for Geophysics on a project to help find and catalog offshore sand resources.

Ultimately, she said she enjoys her role in managing restoration projects and guiding communities on how best to protect the Texas coast.

“You get to implement these large- scale projects, and you go back and visit and you see how much good they have done,” Brooks said. “It’s really great.”

Jack of All Trades

Kiran Sathaye, Ph.D. '16

If Kiran Sathaye has learned one thing in his professional career, it’s that you have to be adaptable.

Sathaye, who graduated from the Jackson School of Geosciences with a Ph.D. in 2016, is a technical sales adviser at Novi Lab, a company that specializes in software for unconventional oil and gas operators. Novi has proved to be a good spot for Sathaye to follow his passion for the energy industry and data science. He has already filled several roles during his three years there — data scientist, chief geophysicist, and now sales — and wouldn’t be surprised if there are more in his future.

“In our company, the roles and needs that existed in 2019 are not the same that exist in 2021,” he said. “That’s just due to the maturation of the company. In a setting like that, you are going to find yourself either having to find a new company or change the way you contribute to success.”

Sathaye proved adaptable even before Novi. That’s how he got into software in the first place. Sathaye entered the Jackson School in 2011 with every intention of going into oil and gas, but as he neared the second half of his doctoral work, he saw signs of a significant downturn in the famously volatile industry.

Sathaye, who earned an undergraduate degree at the University of California, Berkeley, had contacts in the software industry back in California. After a few phone calls, he tweaked his doctoral project to use data tools more oriented to the software industry and graduated with a job offer from Snapchat as a data engineer. After a year and half at Snapchat, he did a short stint as a software engineer at Tala, a company specializing in microloans and operating mostly in Kenya. One thing he learned along the way was that those who major in physical sciences, like the geosciences, are well suited to process data in ways that are relevant for all sorts of businesses.

But Sathaye still wanted to work in the energy industry. So when he was contacted about a possible position at Novi Labs, Sathaye went for it. He finds the growing company a good fit, and as a self-described “jack of all trades,” he likes the opportunity Novi has given him to flex different professional muscles.

He recommends students keep that in mind as they progress. In his experience in business, it’s important to develop soft skills as well as technical skills, Sathaye said, and avoid locking in too much on any single identity. For instance, as a data expert, he said that knowing specific tools is important to get a first job, but from there you really have to be willing to adapt and constantly learn.

“What I have found is that five to 10 years into the industry that jack of all trades thing starts to become very valuable,” he said. “The important thing is to qualitatively understand numbers and understand how data is structured. The tools are going to be constantly changing.”

Hydrogeologist

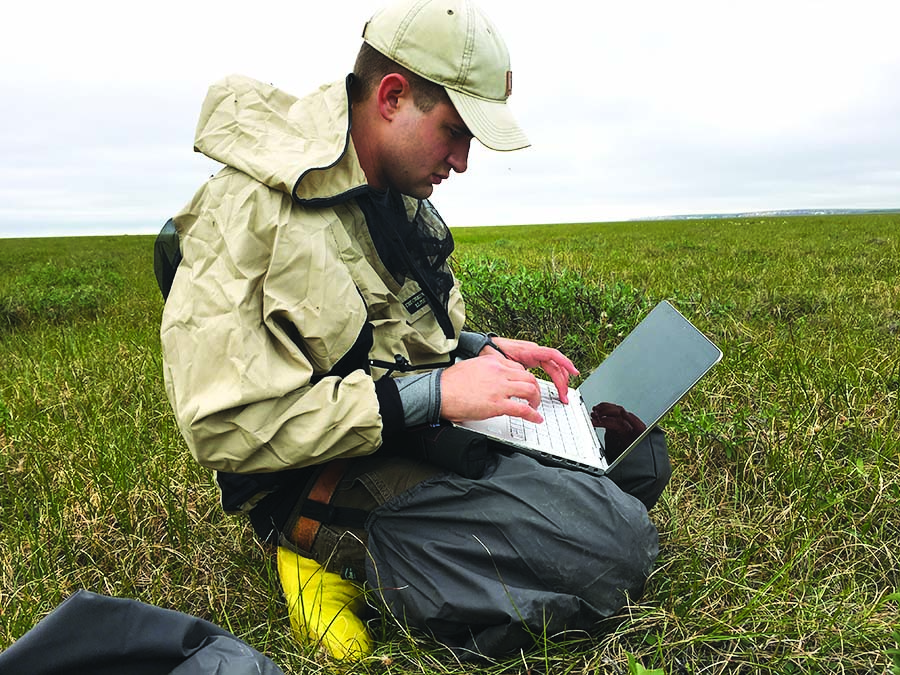

Chuck Abolt, M.S. '15, Ph.D. '19

Chuck Abolt’s introduction to Los Alamos National Laboratory came in 2014 during a Jackson School of Geosciences hydrogeology field camp in New Mexico’s Valles Caldera at a field site that bordered the lab. He found the area beautiful and the idea of working at the lab intriguing, particularly when he discovered it did permafrost work similar to his own graduate research.

Two internships and a couple of degrees later (Abolt earned a master’s from the Jackson School in 2015 and a Ph.D. in 2019), Abolt now finds himself finishing the second year of a three- year postdoctoral fellowship at Los Alamos. His work involves two projects on Arctic permafrost: One focuses on using satellite data to determine where permafrost is thawing most rapidly; the other uses computer simulations to predict how quickly permafrost will thaw over the next 100 years.

Abolt’s move to the national lab didn’t happen by accident. Shortly after he was introduced to Los Alamos, he discovered that the lab uses cutting- edge codes for simulating thawing and freezing through a program called the Advanced Terrestrial Simulator (ATS). He immediately downloaded ATS and began using it in his work.

“That way, when I reached out to the lab, I could say, ‘Hey I already have a little bit of experience using this.

It’s a component of my dissertation and I would love to benefit from your expertise if you could take me on for the summer,’” he said.

This sort of hustling attitude wasn’t a first for Abolt. After high school, he majored in Spanish and biology at Duke University and thought seriously about pursuing a Ph.D. to become a Spanish professor. But shortly after graduating in 2012, he concluded that he didn’t love humanities research and wasn’t sure about his career prospects. He did some online research and came up with a list of valuable degrees that included hydrogeology, which piqued his interest.

Lacking any background in the subject, he emailed professors and researchers at the Jackson School to see whether they could offer advice or, ideally, take him on as a master’s student. The most promising response came from Michael Young, a senior research scientist at the Bureau of Economic Geology.

“I told him, I have a humanities background, and I’m pretty good at technical writing. Maybe I can edit some of your manuscripts or something like that,’” Abolt said. “In the meantime, I read a bunch of textbooks in geology to prepare before I got started in the master’s program.”

It worked. Young employed Abolt as a technical research assistant and was his adviser for his master’s and Ph.D. work.

Two years into his career, Abolt said he is certain he made a good choice.

He would like to stay on as a staff researcher at Los Alamos after his postdoc, which he points out is more common at the national laboratories than at a university. To do so, he said he’s going to have to expand his research out of his current comfort zone. But he said that Los Alamos is the perfect setting for doing so because of its concentration of experts and the supportive environment. For example, he recently started working on a project about small earthquakes in New Mexico.

“It seems like the people who are most successful at the lab are those who are most able to adapt and are undaunted about doing research that is unrelated to anything they have done,” he said. “As different projects and different funding sources come in, you can really make yourself useful.”

Investment Banker

Indre Altman, M.S. '20

Indre Altman’s path through the geosciences took a conventional route for the first few years. She was introduced to the science as a high school student

in the Jackson School of Geosciences GeoFORCE program. This led to her majoring in earth and oceanographic sciences at Bowdoin College in Maine, which fit the bill for the Houston native’s desire to explore the northeast.

It was an internship during her senior year with Asia Pacific Partners in Mongolia where things started getting unconventional and put her on a path that would eventually lead to the investment banking industry.

Altman worked as a mining research intern. Her job was to brief the CEO on contracts and geotechnical reports and write a primer on the Mongolian mining industry. But what really caught her eye were the unique challenges that came with doing business in Mongolia, from the culture and politics to the logistics, financing and fundraising.

“I started to develop an interest in other areas of the mining and energy sectors,” said Altman, who double majored in government and legal studies at Bowdoin.

Looking to expand on these growing interests in graduate school, but still wanting to improve her technical geosciences education, she found the Jackson School’s interdisciplinary Energy and Earth Resources (EER) program a natural fit. She graduated from EER with a master’s degree in 2020 and a job at Lazard as an investment banking analyst specializing in the energy industry.

Altman had been considering investment banking since about the time she started graduate school. She was drawn to the industry because of the strategic role it plays in helping companies grow and remain resilient. Because she wasn’t in a business school, she had to find ways to plug herself into the industry’s recruitment.

“The best advice I can give to people who want to recruit from something in business or finance is to really utilize LinkedIn, friends or other recruiting networks to get those conversations going,” she said.

That’s exactly what Altman did, turning a distant connection into a meeting over coffee with someone at Lazard. From there, she leaned on a friend from high school and fellow UT student who was getting into the industry to prepare her for the challenging interviews.

The work paid off. She landed an internship with Lazard and then the analyst position. She now spends her days modeling transactions and helping administer and manage the logistics of business deals. She said the industry isn’t for everyone, but that it is great for those looking for a fast-paced, competitive environment, and that it recruits from all manner of backgrounds.

The EER program — with its fingers in geosciences, engineering, management, finance, economics, law and policy — really prepared her for the challenge, she said.

“Honestly, the EER program was a lot more challenging than I anticipated, but in a very positive way,” Altman said. “Because it is interdisciplinary, there is a big learning curve in multiple areas.

And for all of those, you have to master a different way of thinking.”

Environmental Insurer

Dana Carstens, B.S. '16

Not long ago, Dana Carstens was unaware that the field in which she now works even existed. As an environmental broker for Willis Towers Watson, Carstens negotiates environmental pollution coverage with underwriters on behalf of her clients.

It may seem like an odd place for a geoscientist to end up, but to Carstens, the fit is perfect. She’s far from alone in this particular niche of the insurance industry.

“Most of the people I work with are geologists or environmental scientists,” she said.

The sites her clients are looking to insure often have long and complicated industrial histories that could leave a legacy of contamination. Understanding how to pore through environmental reports to find a site’s environmental history and comprehend its geological attributes including subsurface flow, soil and water quality and aquifer characteristics are all vital when trying to place and negotiate environmental insurance policies.

It took a few stops before Carstens ended up in environmental insurance.

Carstens comes from a family of oil and gas professionals, but she didn’t want to go that route. She earned an environmental science bachelor’s through the EVS program at the Jackson School of Geosciences and followed that with a master’s in geology from Tulane University in 2018. She loved geospatial and hydrology work and considered going for a Ph.D. and a career at a federal agency like the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, but the specter of five more years of school didn’t sit well. She had heard about environmental consulting in school and thought that might be the right fit.

“In your head it sounds like an exciting career path,” she said. “I just kind of assumed that’s where I would end up.”

She was right. Carstens secured a job as a geologist with the environmental consulting firm Roux after earning a master’s, working to remediate pollution on old industrial sites through groundwater and soil monitoring. She enjoyed putting her geology, geographic information system (GIS) and geospatial skills to work, but said that ultimately consulting was probably not a good long-term fit. Everything changed when her company’s insurance practice leader moved to her office.

“He ended up taking me under his wing, and he introduced me to the environmental insurance world,” Carstens said.

At Roux, the insurance group worked with underwriters to perform loss control evaluations on a portfolio of properties to identify pollution risks and how these risks can affect the company’s insurance program.

She moved to Willis Towers Watson in January 2021 after someone from the company reached out to her on LinkedIn. Moving there has allowed Carstens to work in environmental insurance full time. She now uses her technical knowledge from school and her previous consulting experience to negotiate with underwriters for better coverage on behalf of her clients.

“I get to learn about some really unique locations, and I really enjoy putting my geology background to use in an atypical way,” Carstens said. “I’m very happy with my choice.”

Cloud Manager

Yomi Olufowoshe, B.A. '12

Yomi Olufowoshe’s career path is a lesson in what can be achieved by following opportunity, and of the unexpected places a good geosciences education can take you.

Olufowoshe is an account manager at Google, working with large international clients in the retail, consumer package goods and energy services industries. His duties include helping customers determine how to best use cloud services to increase revenue and market share, reduce costs and solve their toughest challenges.

“It’s not necessarily what I envisioned,” he said. “But it feels right.”

It was a bit of a winding road for him to get there, but Olufowoshe clearly doesn’t mind taking a chance.

For instance, as a high school athlete in Alberta, Canada, Olufowoshe could picture himself at either The University of Texas at Austin or the University of Southern California. Trying to decide between the two, he left his fate up to the outcome of the 2005 National Championship game. So Vince Young’s last-minute end zone dash brought both the crystal football and Olufowoshe to the Forty Acres.

He came with a lifelong interest in geology, but his plan was to pursue an education in medicine and become a cardiac surgeon. That all changed during his junior year when he took Jackson School of Geosciences Professor Chris Bell’s Life Through Time class, which reawakened his passion for the geosciences.

Because of the late change, Olufowoshe didn’t have much time to map out his postgraduation plans. As an undergraduate, he had heard that a master’s degree was needed to forge a career in the geosciences, but he wanted to get some experience under his belt before he made any other big decisions.

“I thought, ‘Let’s explore this industry a bit to identify what about it piques my interest,’” he said.

It was a late internship opportunity with Landmark, the software arm of Halliburton, that set him on his path. Landmark liked him so much that they offered Olufowoshe a full-time job in the quality assurance department. His job entailed looking for bugs and defects in the software before it was released and working with the development team to fix and document the issues.

This gave him the opportunity to apply geological concepts he studied in school while testing the software, sometimes with eye-popping results.

“The interpretation I had done in class was all by hand,” he said. “The first time I was able to do a full correlation just by clicking through with a mouse, my mind was blown.”

Olufowoshe filled several roles at Halliburton, transitioning from his position in quality assurance to a product manager and then to a global sales role where he dealt with large oil companies and international accounts. Eventually, he was stationed in Italy where he helped with training and served as liaison between Eni and Landmark.

Olufowoshe’s journey up the ladder at Landmark eventually got the attention of Google. He discussed multiple potential roles with the company before accepting his current position, which he started in April 2021.

Olufowoshe is still extremely active in the Jackson School. He serves on the Geology Foundation Advisory Council, has been a GeoFORCE mentor, and regularly talks with students. He’s a proponent of all that a geosciences education has to offer, particularly the ability to think critically and solve problems.

He also encourages students to get to know professors and scientists and to take every research opportunity available. Those relationships, he said, can reveal new horizons.

“When I was in school, you were really only shown a few options career- wise,” he said. “There are so many opportunities that are available, and without that exposure, you really don’t know what’s out there waiting for you.”

The University of Texas at Austin

Web Privacy | Web Accessibility Policy | Adobe Reader