THE END OF AN ERA

After 24 years leading the Bureau of Economic Geology, Scott Tinker is stepping down, leaving behind a deep legacy at the storied institution

BY ANTON CAPUTO

It is difficult to put the Bureau of Economic Geology into a tidy box. It is the oldest research unit at The University of Texas at Austin, dating back to 1909, and the second largest. Yet it doesn’t rely on faculty members for leadership or research.

It is a place where hundreds of students have received valuable hands-on experience and mentoring over the years, but education is not the major focus. It is a research institution organized more like a national lab than an academic department, and it is the state of Texas’ geological survey, meaning it has an official role in informing state policymakers about the natural resources and the environment of Texas.

And looming over all this is the fact that it is largely a soft money institution, meaning its very lifeblood depends on attracting external investment from industry partners, science foundations and government agencies. If not, it withers.

Given this combination of factors, it takes a versatile and visionary individual to successfully lead the bureau. For over two decades, that person has been Scott W. Tinker. Now, after 24 years at the helm, Tinker has decided that the bureau would benefit from new leadership.

“I am firing myself!” he said. “It’s been a remarkably great ride. But I think it’s time for somebody new to take the helm. I could probably do another 10 years, and things would be fine. But this is the right time for new ideas, new energy and new innovation. I believe that the best thing I can do for the bureau is create an opportunity for that to happen.”

Tinker’s impact is undeniable. He has been instrumental in starting a host of high-profile research programs. He has spearheaded the addition of major facilities such as the Houston Research Center, the Austin core repository, and many research labs. He played a pivotal role in the formation of the Jackson School of Geosciences, helping secure the foundational gift from Jack and Katie Jackson as part of a small group of people that Jack Jackson dubbed “The Jackson Five.”

Tinker has been a tireless advocate for energy and environmental education and communication through film, television, radio and other media. But mostly there’s the seemingly boundless commitment to promote — and sometimes protect — the bureau in a dizzying array of arenas that includes academia, industry, international business, nongovernment organizations, the Texas Legislature, and national policy debates.

Bill Fisher, a former bureau director and founding dean of the Jackson School, said that Tinker’s success is rooted in understanding the needs of a unique organization like the bureau and being able to thrive in the uncertain environment it takes to lead it. This takes a rare skill set that involves understanding how to look for and develop new research opportunities, even in areas outside of your expertise, and knowing how to go about opening the doors and forging the relationships to make them happen.

“That involves somebody who is willing to get out of the office and have a lot of visibility. Scott appreciated that very quickly,” Fisher said. “That visibility helps a whole lot in trying to attract and keep the money flowing. All the good ideas in the world aren’t worth a damn if you don’t have the money, and same for all the money in the world if you don’t have good ideas. Scott is very intelligent. He has good ideas and he pushes them.”

Time for a Change

When Tinker decided to throw his hat into the ring for the top spot at the bureau nearly a quarter-century ago, it was the opportunity to grow something “unique” that drew him. He was particularly intrigued by the bureau’s position at the nexus of academia, industry and government.

At the time, Tinker was coming from a 17-year career mostly in the research side of the oil industry, where he was an advanced senior geologist at Marathon Oil’s Petroleum Technology Center in Littleton, Colorado.

He was familiar with the bureau from its national reputation and through fieldwork with bureau researcher and current Jackson School Professor Charlie Kerans.

The two met in the field in the late 1980s when Kerans had just started the bureau’s reservoir characterization research lab. Kerans remembers Tinker being tremendously energetic in the field and on the cutting edge of the latest technology and research.

“Scott was pretty much at the forefront of 3D modeling technology,” Kerans said. “He pushed a lot of the technology forward very quickly and very effectively.”

The two kept in touch for years, teaching short courses together on carbonate reservoirs and publishing a book together in 1997: “Sequence Stratigraphy and Characterization of Carbonate Reservoirs.” So, when the bureau was looking for a director, Kerans was thrilled to hear about Tinker’s interest. But he was also surprised, given that Tinker would have to leave a thriving research career for administration.

Tinker and his family also had much going on at the time. He and wife Allyson had a busy family life with three young boys — Nathan, Derek and Tyler. But it was an era when most major companies were closing research labs. At the bureau, Tinker saw an opportunity to make a move to a place where he could grow and diversify research.

“I saw the opportunity to create something that the world recognizes,” Tinker said. “I thought, what a bunch of great clay. Let’s try to mold this.”

Needless to say, he got the job.

Broadening the Scope

When Tinker entered the bureau in January of 2000, there was a lot of work to do. The research unit was at a financial low point. Previous leaders had focused on a few international projects, which had petered out for a variety of political and economic reasons. Fisher had stepped in as interim director to stabilize the situation and to find the next permanent director. When he met with Tinker for a breakfast meeting in Denver during the annual Geological Society of America meeting in 1999, he immediately saw the potential.

“I found the guy tremendously articulate and pretty darn insightful,” Fisher remembers. “I went back and told Doug Ratcliff (bureau associate director), I think I just found our next director.”

The next 24 years would be defined by growth at the bureau. Research funding grew from about $10 million a year when Tinker took over to more than $30 million a year today. The number of employees grew from fewer than 100 to about 250. And with the exception of temporary furloughs that were necessary during the worst of the COVID-19 pandemic, staffing at the bureau has been remarkably stable.

“We have had folks here 30 to 40 years or more,” Tinker said proudly. “As long as they are actively contributing and happily engaged, the bureau is a great home. At the end of the day, our success is mostly about our people. When I arrived, the first thing I did was write a list of names and technical disciplines on a white board. We have since hired over 500 people.”

Much of that growth and success can be linked to Tinker’s deft navigation of a changing energy and environmental landscape in Texas, across the nation, and around the globe. Oil and gas still remain the backbone of the energy system, but energy sources are diversifying as lower-emissions technologies and options are added. And there is a growing recognition of the need to understand the broader effects of energy production, including emissions and other environmental impacts. Tinker has made sure that the bureau has stayed ahead of the curve when it comes to conducting research in these areas.

Some of the programs that have either started or significantly expanded under Tinker’s leadership include: the most comprehensive public study of the nation’s seven major shale plays; the state’s seismic monitoring system, TexNet, and a related research consortium to understand the cause of increased seismicity in Texas, CISR; a plethora of research consortiums, including ones in hydrogen energy, geothermal energy, unconventional reservoirs, mudrocks and computational seismology; the Gulf Coast Carbon Center, the nation’s top carbon storage research program; a cutting-edge subsurface micro- and nano-sensor program; and recently, a project to conduct a cradle-to-grave analysis to determine the environmental impact and cost of electricity generation options.

“He built great programs and he certainly put the name of the bureau on the map across the country and beyond,” said Sharon Mosher, who was dean of the Jackson School from 2009 to 2020. “He really grew the bureau into what it is today.”

Spreading the Word

At the same time Tinker helped build the bureau into a research power house, he has been a tireless advocate for energy and science education in the public sphere.

He conceived of and is the voice of “EarthDate,” a radio program produced by the bureau with a reach of more than 450 radio stations in all 50 states and abroad. “EarthDate” will air its 350th episode in January 2024. He conceived of, hosts and moderates the TV talk show “Energy Switch,” which reaches over 100 million households on PBS and explores hot-button topics in energy and climate with two global experts as guests on each show.

Tinker is also the founder and chairman of the Switch Energy Alliance, an energy education nonprofit. The organization offers free K-12 classroom curriculum and materials used by thousands of teachers nationwide, hosts an international case competition for college students, and creates documentaries and educational films and videos. With director Harry Lynch, whom Tinker describes as brilliant, patient and creative, Tinker has co-produced and been the onscreen guide in two feature-length documentaries, “Switch” and “Switch On,” which explore the global impacts of different energy sources. This includes shining a light on “energy poverty” — the array of impacts that communities with unreliable access to energy face — and the myriad benefits that come with expanding access to energy.

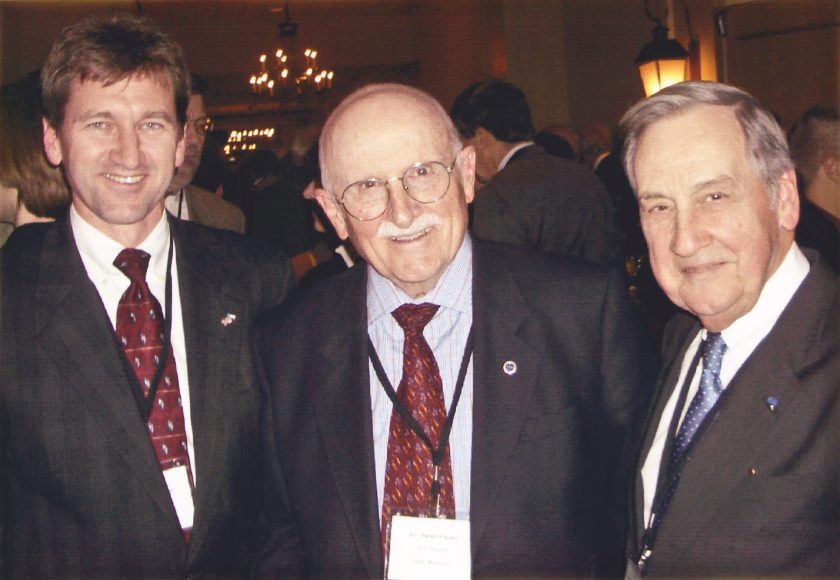

The past 24 years have also given Tinker the opportunity to mix with heavy hitters inside and out of the public policy realm.

“I met Henry Kissinger and Walter Cronkite, many state governors and Cabinet secretaries, Earl Campbell and Andy Roddick, dozens of industry CEOs, university presidents and elementary students,” he said. “It has been an incredible ride, really.”

Yet, when Tinker looks back on his years and accomplishments, he doesn’t focus on specific research initiatives or movie premieres, but instead dives into the commitment and support of the people around him.

Wanda LaPlante, who served as Tinker’s first executive assistant for a decade, said that during his early days at the bureau, he spent long hours getting to know everyone in the organization by meeting and listening to people. She remembers being struck at how Tinker and Allyson balanced the demanding new life with three young sons, and daughter Claire soon on the way.

“It was very much a family feeling for me,” she said. “He (Tinker) really cared. He’s very compassionate and really wants to do the right thing.”

The bureau’s culture under Tinker also became distinctly international. He likes to quip that when he first started, the bureau employed people from three countries: Texas, Oklahoma and Louisiana. Now, there are full-time staff members at the bureau from six continents representing at least 25 nations. That’s a tribute to the bureau’s global reputation, he said, and its efforts to cast a wide net to bring different skill sets and perspectives to solve scientific problems.

“We’ve got different cultures, socioeconomic backgrounds, educational backgrounds, government systems,” Tinker said. “That type of diversity is not always easy to manage, but very powerful.”

Looking back on his years at the bureau, Tinker said he has reflected on what it has meant to him. He credits many people with helping along the way, particularly wife Allyson, his visiting committee members, wise researchers such as Martin Jackson and Shirley Dutton, LaPlante, state geologist colleagues including Jon Price and Nick Tew, and past directors Fisher and Peter Flawn (a former UT president and bureau director who passed away in 2017). These and many others were always willing to lend an ear and their counsel, he said.

“I had lunch with Peter Flawn a few days before he passed,” Scott recalled. “He chaired the bureau’s visiting committee that I formed back in 2000 and remained a wonderful mentor. Peter was a man of few words, but said to me that day, ‘I often wonder what would have happened to the bureau if you had not arrived.’ That meant a lot to me.”

Teamwork is Key

The bureau became part of the Jackson School in 2005, when the school was formed. Although an academic unit, it operates more like a research business, from how research is funded to how teams of scientists are organized, to how it is staffed.

For instance, being a soft money organization, the bureau can’t run its account balances down to zero at the end of a fiscal year.

“Our full annual budget does not arrive at the beginning of each fiscal year. Instead, we are on a continuous treadmill to bring money in to support our scientists throughout the year,” said Deputy Director Jay Kipper, who has acted as a combination of chief financial officer and chief operating officer for two decades. “It’s very different than the way the rest of the university works.”

And on the research side, it is common for bureau research teams to employ engineers, scientists, economists and experts from other fields on a project. According to Tinker, this creates an environment where fundamental research is conducted in service of practical problems, and where researchers can thrive and expand their impact by working as a team.

Senior Research Scientist Julia Gale said this arrangement benefits the science and scientists. She began her career at the bureau just before Tinker took over. She was a little nervous about the soft money aspect of the organization, particularly since it was at a time when the organization was facing funding issues and looking for a new leader.

Very soon, she said, she was immersed in a “phenomenal team atmosphere” while working at the bureau’s Fracture Research and Application Consortium (FRAC) that was unlike anything she had experienced at academic institutions. And she found the bureau under Tinker’s leadership to be very nimble and thoughtful with its employees, allowing them to move from one project to another to align skills with the available opportunities.

“One of the advantages of being in a team is that if you don’t have a good idea, maybe somebody else will,” Gale said. “That’s a nice dynamic to have. You try your best to get good ideas and follow through, but you know that the others in the group are going to have your back.”

Michael Young, a senior research scientist at the bureau and current Jackson School associate dean of research, served as Tinker’s associate director for the environmental division from 2010 to 2020. He came to the bureau from the Desert Research Institute, where he was acting executive director of the Division of Hydrologic Sciences, which he describes as a fairly typical academic setting. One of the keys to the bureau’s success, he said, is finding people who can thrive under the research model that Tinker has nurtured.

“We focus on people who really want to do collaborative research,” Young said. “We have a lot of broad, comprehensive research groups and programs that are successful. That is really a totally different type of model than you would see at most academic departments.”

A Lasting Legacy

One of the overarching accomplishments that Tinker is credited with is diversifying and expanding the bureau’s funding sources and research initiatives by keeping the bureau active on the national and international scenes. International examples include major projects with Pemex, Mexico’s national oil company; several projects in China; a carbon storage research agreement with Trinidad and Tobago; and a resource analysis project in Timor- Leste. But nowhere has the success been more evident than inside the state of Texas and with the bureau’s role as geological survey.

Every state has a geological survey. Their roles vary, depending on the laws and traditions of each state, but most act as a resource for legislators and policymakers. According to Nick Tew, the director of the Alabama Survey and former president of the Association of American State Geologists, under Tinker’s leadership the bureau has become a geological survey that stands apart.

“The main difference is that the bureau is a very large survey that operates on an entrepreneurial model,” he said. “Success under this model requires visionary and creative leadership from the director and senior staff. Scott and his team have provided this type of leadership for 24 years.”

Successes include funding for the statewide TexNet seismic monitoring system and the connected research consortium Center for Injection Seismicity Research (CISR) to address increased seismic activity, working with the General Land Office on coastal erosion issues, and other projects with the Texas Water Development Board, the Texas Railroad Commission and the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality.

There’s also the state’s investment in the bureau’s STARR program, which conducts research to increase the production and profitability of the state’s earth resources, to support public education. Since its founding in 1996, state funding has grown from about $500,000 a year to $5 million a year. That increase, Tinker said, came under the leadership of state Comptroller Susan Combs, who was a member of the bureau’s Visiting Committee at the time.

And it has certainly paid off. Over $500 million — or 13 times the cost of the program — has been returned to Texas through increased royalties and severance taxes since the program began.

Kerans credits Tinker directly with fostering the bureau’s relationship with state agencies. Before Tinker arrived, he describes the bureau as having little status or influence in the Legislature. “I think Scott had gotten us to a point with the state where we never were,” he said.

According to Young, much of the success experienced by the bureau during Tinker’s tenure stems from Tinker’s ability to hire the right people as his associate directors and trusting them to do their jobs. This has freed up Tinker to forge the relationships that will ultimately pay off in research support, and to stay ahead of important scientific trends and needs.

“Scott has the job of flying at a 30,000-foot view, looking at how things are going to change in the next three to five years, and trying to make those connections and getting those doors open,” Young said. “He opens those doors, and then eventually it’s up to us to make a compelling case for the work we want to do.”

Tinker agrees with Young’s assessment of the bureau’s associate directors and points to them as key to the bureau’s success, particularly with the flat organizational structure.

“My associate directors are remarkably talented and highly experienced leaders,” Tinker said. “They bring deep industry and military experience to the bureau, run their divisions, and we knit it all together into a nice bureau fabric. It’s vital for me to delegate responsibility and authority, and support them behind the scenes so that they can do their jobs effectively.”

According to Kipper, that involves keeping one simple reality in mind.

“We try to eliminate bureaucracy and excessive management so that the researchers can really focus on their research and get it out in publications and presentations, because at the end of the day, the bureau’s reputation is built by our people.”

Even with Tinker stepping down, he is not likely to disappear any time soon.

He’s staying until a replacement director can be found and then will take on a part-time role based in Houston. There, he will continue his work to “open doors” for bureau researchers. He also plans to continue lecturing around the globe — he does an average of 60 keynote and invited lectures a year at conferences, universities, in board rooms and beyond — and advancing energy education. This includes his work on energy poverty, an effort to ensure that energy-poor nations aren’t forgotten as the world continues to search for the energy answers of the future.

There have been only eight directors in the bureau’s 114-year history.

Tinker said it’s an honor to be among them.

“It has been a true privilege to serve the bureau. It provided a unique opportunity for us to impact global society in a meaningful way,” Tinker said. “Now it’s time for someone else to have that remarkable opportunity.”

Scott Tinker at a Glance

Education |

|

Professional and Academic Service |

|

Current Boards, Councils and Commissions |

Academia

Federal and State Government

|

Policy and Government |

|

Awards |

|

The University of Texas at Austin

Web Privacy | Web Accessibility Policy | Adobe Reader