From Pandemic Setback to Research Project

When the coronavirus brought travel to a halt, Professor Bayani Cardenas and his research team took his deep-diving science to Lake Travis

Bayani Cardenas is a geoscientist and a diver.

A professor at The University of Texas at Austin Jackson School of Geosciences, Cardenas studies how water interacts with the environment. He often does it by suiting up and diving in to collect data himself.

His research takes him and his students around the world, from permafrost-covered shorelines in Alaska to coastlines along the Philippines bubbling with volcanic gases.

But in 2020, the coronavirus pandemic brought all that to a sudden halt. In-person classes were cancelled. So was most travel.

Cardenas started brainstorming about how to make the best of a bad situation. He decided to bring his deep-diving science to Lake Travis, coming up with a research project that students and researchers from his lab could carry out from the lakeshore.

“During the pandemic, I knew we could be here safely,” Cardenas said. “We could be at picnic tables and see each other…and my students kept up on their skills on how to collect water samples.”

So, starting in September 2020, the team started making monthly visits to the lake to track its seasonal water turnover.

Lake turnover is when otherwise stratified layers of water at the top and bottom of the lake mix in response to temperature changes that occur during the spring and fall. The mixing process circulates oxygen and nutrients throughout the lake, helping to rejuvenate lake ecosystems.

And though assumed to be happening in Lake Travis, no one had ever studied it.

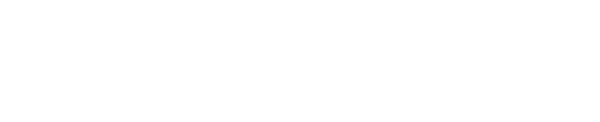

During the monthly visits Cardenas and his project dive partner, UT undergraduate student Jacob Mehr, dove 150 feet to the lake bottom — or as close as they could get if the water was too murky — carrying along a scientific instrument that measured temperature, depth, dissolved oxygen, carbon dioxide, and salinity every few seconds. They also collected a water sample from the lake bottom.

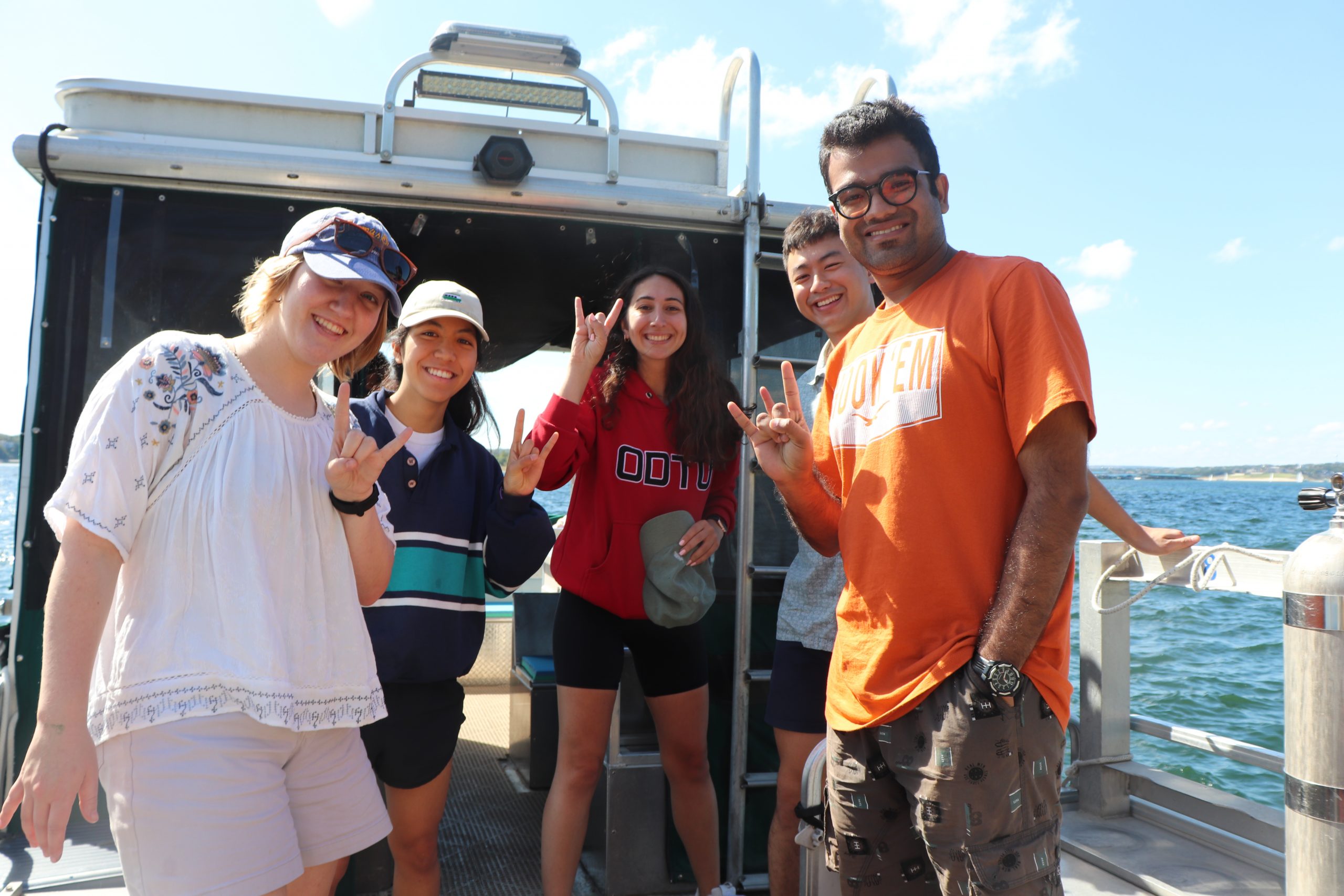

Back at the surface, members of the research team took surface samples and waited for Cardenas and Mehr to return so they could process the water sample and upload the data.

“When I’m here, I’m basically just a diver,” Cardenas said. “They’re in charge of all the science.”

Last month, in November 2021, the team passed a full year of sampling. Their data clearly shows that lake turnover is happening in Lake Travis. But much more has happened along the way, with the pandemic project turning into a full-fledged undergraduate research thesis for UT chemistry and physics major Morgan Teel, who joined the research team in spring 2021.

Teel said her interest in water chemistry started during the early days of the coronavirus pandemic. She was fascinated by reports of cloudy water canals clearing up in Venice, Italy, the result of the pandemic restrictions shutting down traffic and allowing suspended sediment to finally settle.

That fascination got her wondering about the connection between environment and water quality, and led her to enroll in Cardenas’ Introduction to Hydrology course.

When she asked Cardenas about research opportunities, he invited her to join the research team out at Lake Travis. Shortly after, Teel took on the project as her undergraduate research thesis.

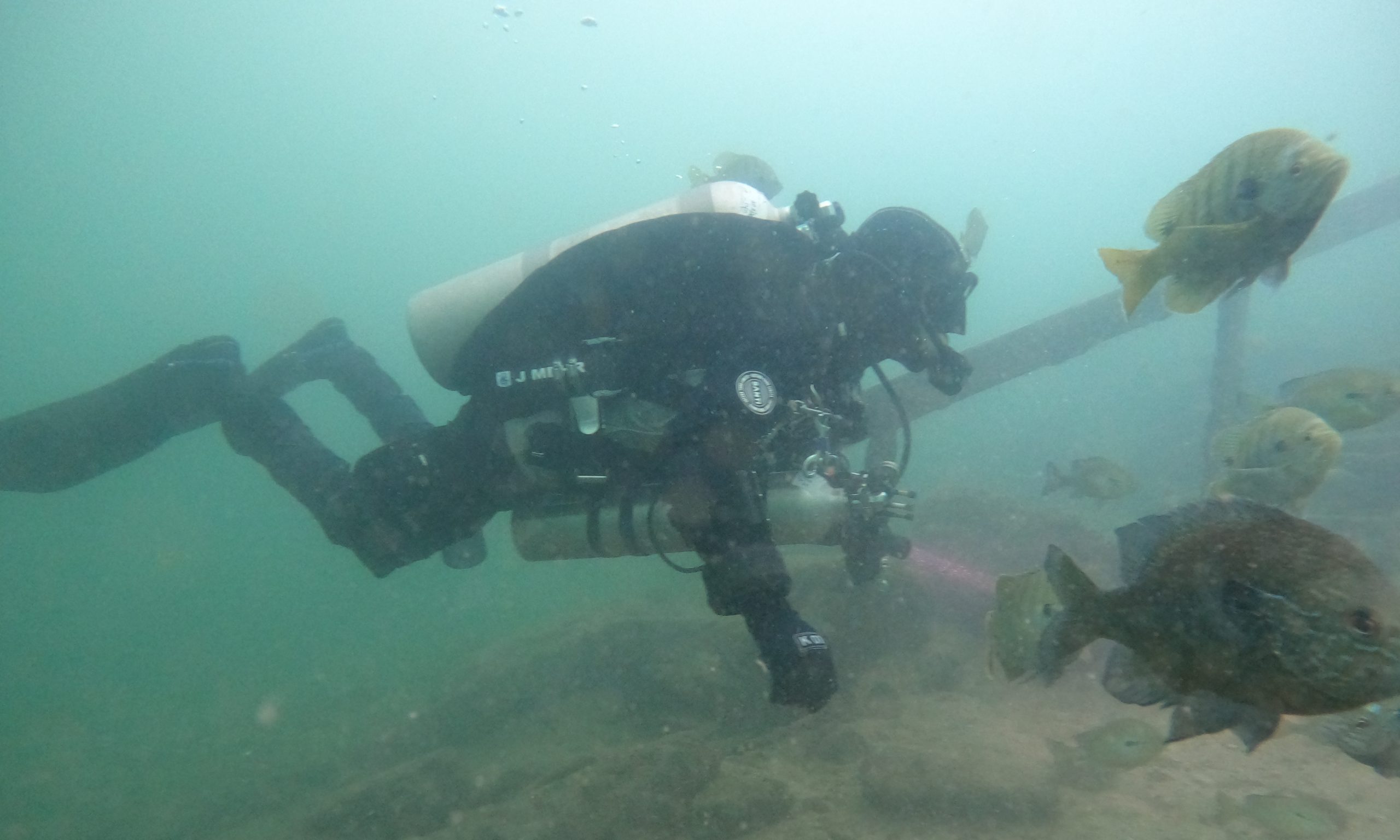

The temperature data collected by Cardenas and Mehr alone show that lake turnover is happening. In January, the lake is about the same temperature at the surface and bottom, enabling mixing. By August it has has stratified into two distinct temperature layers, the surface being 85 degrees Fahrenheit, the bottom around 53 degrees Fahrenheit.

For her thesis, Teel is analyzing what this stratification and mixing means for the lake’s water chemistry, how its oxygen isotopes, carbon, and alkalinity change with the seasons.

These metrics are related to ecosystem health and could help reveal how the lake’s habitability changes over the year. Her data will also serve as a baseline comparison for future studies on the lake’s water chemistry.

“It’s one thing to say the lake stratifies, that’s good to know, but the next step is what does that mean in terms of organisms and chemical reactions,” Teel said. “The chemistry is helping us know the consequences of that.”

The project has been a learning opportunity for Cardenas, too. He said that he has Mehr, his dive partner, to thank.

Mehr is an engineering major who has been diving for half his life. He learned about Cardenas’ diving research in 2018 from a social media post, and reached out about opportunities to take part. There was nothing available at the time. But when Cardenas needed a diving partner for the Lake Travis project, he knew exactly who to call.

Mehr is a member of Global Underwater Explorers, a diving organization that trains its members to treat every dive like it’s a technical one, where divers can’t necessarily return to the surface if they hit a snag. Members carry standardized equipment, follow protocols for packing tools and troubleshooting problems, and learn to breathe a special blend of gases that keep nitrogen from building up in the blood where it can lead to disorientation.

By diving with Mehr, Cardenas has picked up a whole new diving skillset.

“My personal development as a diver who uses science for diving has elevated,” Cardenas said.

Jackson School of Geosciences Ph.D. candidate Cansu Demir said that being part of the research team has been a lesson in how obstacles can become opportunities. In 2020, she wasn’t able to conduct fieldwork in Alaska as planned. But by taking part in the Lake Travis project she saw how Cardenas turned an idea into tangible student research – even in the midst of a pandemic that shut everything else down.

“It’s cool because I’m learning from this,” Demir said. “The professor comes up with a cool idea, it turns into a big project, and now there is an undergraduate conducting research on this. This is how projects form and students make their thesis out of it.”

Teel is currently doing just that. She expects to have the results in early 2022.

The University of Texas at Austin

Web Privacy | Web Accessibility Policy | Adobe Reader