Dalziel Honored with Penrose Medal

Longtime Jackson School Professor wins Top Geology Award

Ian W.D. Dalziel, a professor in the Jackson School of Geosciences at The University of Texas at Austin, has been awarded the Geological Society of America’s Penrose Medal for pioneering discoveries about Earth’s ancient geography and its past supercontinents. Established in 1927, the Penrose Medal is widely considered to be geology’s most prestigious career award.

In a letter, GSA Past-President Doug Walker said that Dalziel’s scientific contributions marked a major advance in the science of geology and shed new light on key periods in our planet’s distant past, such as the “Snowball Earth” and the “Cambrian Explosion” of multicellular life.

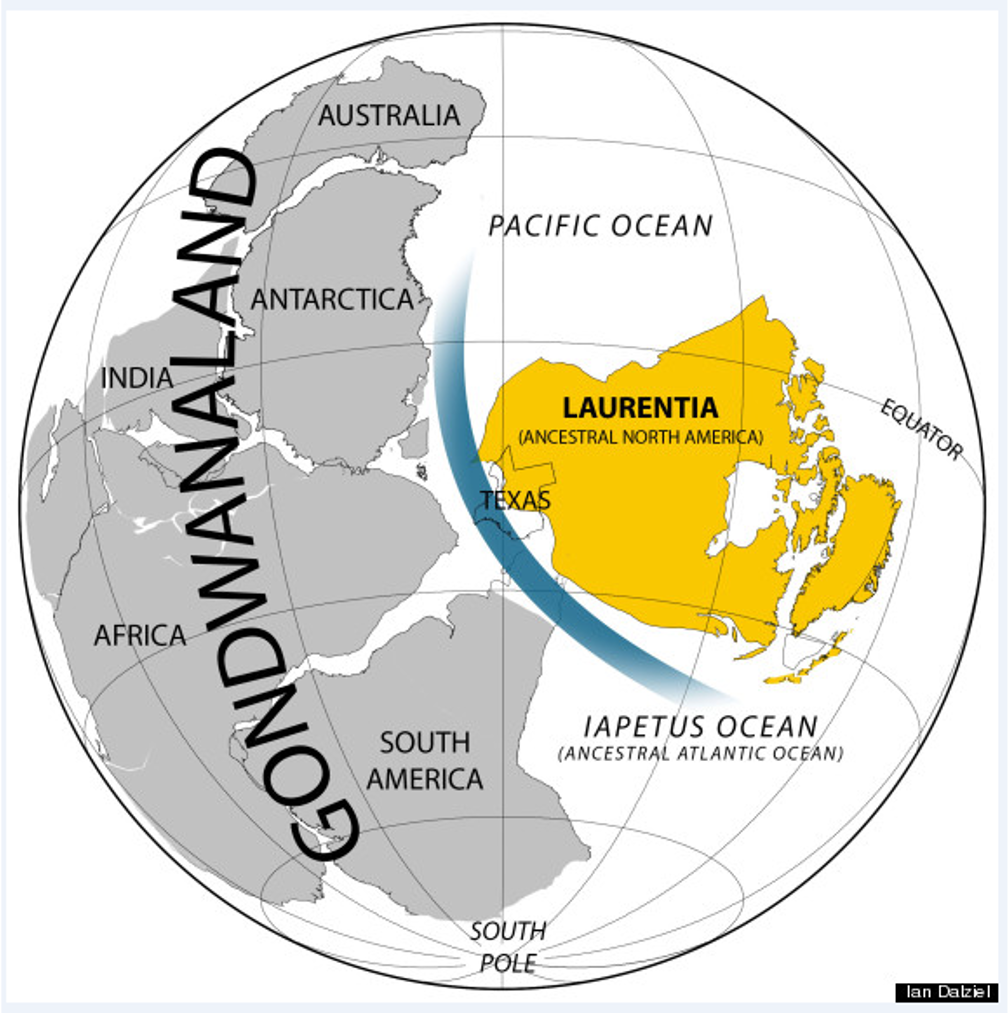

Dalziel’s work has been important in reconstructing the position of our planet’s past continents. His discoveries include evidence that half a billion years ago, during the Cambrian Explosion, Texas lay alongside Antarctica. He also uncovered geology showing that 50 million years later it was part of a large plateau joining ancestral North America to the Andes of Argentina. These and other discoveries spurred a new interest in the geography of our planet from before Pangea, the last time Earth’s landmasses assembled as one, and inspired the idea that other supercontinents had previously existed.

“Ian has certainly earned his place among geology’s scientific giants” said Demian Saffer, director of the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics (UTIG) where Dalziel has worked since 1985. “He is a prolific field scientist whose vision exemplifies the spirit of discovery that is at the heart of UTIG’s mission.”

This year’s award is the fifth time that a Penrose Medal has gone to a faculty member or an alumnus of UT’s Jackson School. Past recipients include the legendary oceanographer Maurice “Doc” Ewing (UTIG’s founder) and former Jackson School faculty member Robert Folk.

The award was announced in the July issue of GSA Today.

Dalziel became fascinated with geology at an early age when, as a child, his parents took him on weeks-long treks across the islands and Highlands of Scotland—where he is from. After graduating from the University of Edinburgh with a Ph.D. in geology, Dalziel joined the University of Wisconsin-Madison in 1963, and the Department of Geology and Lamont Doherty Geological (now Earth) Observatory of Columbia University in 1968. His first breakthrough came in 1973 when he visited South Georgia, an inhospitable island about 1,000 miles to the east of Cape Horn. There, he found identical geology to that he had encountered in the southernmost Andes of Chile and Argentina: proof that until at least 100 million years ago, the now distant places were joined, an important idea at the time considering many geologists were still adjusting to the new paradigm of plate tectonics.

The discovery earned Dalziel an honorary membership with the Argentine Geological Association.

“Ian had energy, expertise and willingness to work in places no one had worked before,” said Victor Ramos, who was the association’s president at the time and is now professor emeritus at the University of Buenos Aires. “Most importantly, he worked closely with the scientific community in Chile and Argentina. That way of working was very welcome in South America at the time.”

Dalziel continued searching for signs of Earth’s tectonic history in Antarctica, where he and his colleagues found that the West Antarctic Ice Sheet—the least stable on the planet—lies on an archipelago made up of distinct blocks of crust, all of which had moved, and might still be moving separately. After joining UT in 1985, Dalziel led a team that placed a network of GPS receivers across West Antarctica. For the first time, scientists watched the bedrock rise as the weight of the ice melted away. The findings helped raise the alarm that Antarctica’s melting ice was a more urgent threat to global sea level rise than anyone had expected.

Perhaps Dalziel’s most noteworthy contribution, however, is research that led to the theory of supercontinent cycles—the idea that every several hundred million years, Earth’s continents merge into a single landmass. In 1989, he convinced 25 of the world’s top geologists to accompany him on a field trip to Antarctica where he had a hunch he might find physical clues to Earth’s geography prior to the assembly of Pangea, the only known supercontinent at the time.

“The idea was to bring Antarctic geology into the global mainstream,” Dalziel said

It did. Ideas sparked by the expedition kicked off a wave of research that opened the way to testable hypotheses about pre- Pangea geography, past supercontinents and their sway over global environments. Now in his 80s, Dalziel intends to continue seeking answers (and adventure) in far flung places.

“There’s always connections to be made over the horizon,” Dalziel said, who is currently planning a return to South Georgia. “There’s so much geology out there in some ways choosing where to look for the right clues becomes almost a measure of scientific taste.”

Ian Dalziel was presented the Penrose Medal on October 10 during a ceremony at GSA Connects 2021 in Portland, Oregon.

The previous Jackson School recipients of the Penrose Medal are Department of Geological Sciences faculty members Bob Folk (2000) and “Doc” Ewing (1974), Bureau of Economic Geology research scientist Preston Cloud (1976), and Department of Geological Sciences alumnus John Crowell (1995).

The University of Texas at Austin

Web Privacy | Web Accessibility Policy | Adobe Reader