<p>

<p>

Face Masks, Zoom and Geosciences

How the Jackson School is Handling Coronavirus

By ANTON CAPUTO & MONICA KORTSHA

On Aug. 26, 2020, the first day of the fall semester, it was empty and quiet on The University of Texas at Austin campus. That’s because for most students and faculty members, going to class meant logging on to their computers from home.

By this point, they had plenty of practice. The onset of the coronavirus pandemic shut down campus in March and transitioned all classes online. And although the university went into the summer with high hopes for a return to in-person learning, by the start of the fall semester only about 5% of classes were happening face to face, or more accurately, face mask to face mask. About 76% of classes remained online, and 19% were hybrids that combined online learning with in-person components. Keeping the UT community safe during the pandemic has touched every aspect of university life. Mainly, it has meant finding ways to do things apart that were once done together. Just 16 days into the semester, UT accounts racked up a total 1,219,621 hours on the remote conferencing platform Zoom, which is being used for everything from meeting with colleagues to lectures.

At the Jackson School of Geosciences, it has meant transitioning to whole new ways of teaching geosciences classes, conducting research and building community.

Note: The UT and Jackson School coronavirus response is a constantly evolving situation. Some parts of this article might be out of date by the time of publication. For the latest news on the UT coronavirus response, visit: coronavirus.utexas.edu

THE BEGINNING

The transition officially started March 17, 2020, when then-UT President Gregory L. Fenves announced that all classes would be moving online for the remainder of the spring semester. Faculty members, researchers and staff members throughout the university faced a monumental task. They had just two weeks to transition classes to a virtual setting, communicate the new reality to students, and prepare for a whole new way of teaching and operating the university. That’s not to mention setting up funds for students with emergency needs such as providing a computer and access to the internet, along with more pressing issues such as assistance with food, rent and medical bills.

All in all, the UT-wide efforts involved moving more than 49,000 students online in more than 9,000 classes. For then-undergraduate student Rachel Breuning, who graduated from the Jackson School later in the spring, it meant rushing back to Austin with her parents to grab her belongings from the residence hall and heading back to Houston, where she finished the remainder of the semester from her childhood bedroom.

“It’s happening to everyone, so I don’t feel like I have a right to feel that bad about it,” Breuning said. “I feel we all are just kind of doing the best we can with what we have.”

During these tumultuous early days, UT and the Jackson School stressed compassion in education, making accommodations wherever possible. “The greatest challenge has been to always remember to be aware of the very different circumstances that our students may find themselves in, with respect to having the electronic resources, the bandwidth, the time and space, and support at home to do their schoolwork,” said Jackson School Dean Claudia Mora. “For some, this change placed them in environments where meeting their educational goals can be very, very difficult. Faculty and staff have faced their own challenges, as many are also sharing their workspace with children home from day care or school, and spouses who are also trying to work from home. We have had to all develop greater sensitivity to each other and greater flexibility in our expectations.”

GEARING UP

All schools and colleges faced their own obstacles. But for the Jackson School, with its focus on hands-on experiential learning, the difficulties were significant. Taking students to the field was out, as was working in the lab and the tactile experience of handling specimens.

The job of spearheading the Jackson School’s sprint to online classes fell to a volunteer ad hoc committee led by professor and incoming chair of the Department of Geological Sciences Daniel Stockli, writer-in-residence Adam Papendieck, and IT staff members Adrian Huh and Tyler Lehman. The committee has remained an invaluable resource into the fall semester, said Associate Professor Elizabeth Catlos, with the team providing advice on a variety of online learning needs ranging from microphones to managing meeting security.

“That group provided a great service to make the transition to online teaching less of a challenge,” Catlos said. Papendieck had significant experience with online learning in a previous position at Tulane University, where he developed systems and programs to support international health sciences education, particularly in eastern Africa. He also had the experience of helping Tulane reopen after Hurricane Katrina ravaged New Orleans in 2005. There are some benefits to the frenzied energy of an emergency, he pointed out: No one balked at embracing the new environment. Everyone recognized the need and committed to do their best to adjust.

More importantly than just mastering the technical challenges, however, were the sessions on how best to create an interactive and effective online learning environment, how to take advantage of online resources and how to handle online assessment and testing.

Most instructors had little or no experience with online teaching, meaning they were entering a whole new world of education and instruction, Stockli said.

“We urged instructors to maintain a rhythm, including maintaining class times and office hours,” Stockli said. “We advised instructors of small classes to continue live lectures via Zoom and make the recording available via internally accessible cloud archives in Canvas. In contrast, large classes were advised to either go live or with prerecorded 15-minute segments interspersed with live discussions.” During this transition to a new learning model, graduate teaching assistants were among those who were leaned on the hardest, Stockli said. Typically, teaching assistants learn to teach by watching their mentors. But in this situation, there was no playbook or example, and they often were the ones with the important job of leading students in labs and other small group settings.

“They were transformed into instructional designers overnight in a way that they hadn’t before,” Stockli said. “And we really stressed with TA’s that they are absolutely essential in community building. We emphasized that they cannot just be instructors but have to be the connection to the students.” This reality hit home with Alexandra Lachner and Jaime Hirtz, who were teaching assistants in the spring field methods course.

They quickly found themselves helping students navigate virtual field outings largely on the fly and spending additional time offering support and guidance to students. They extended office hours and met students one-onone for virtual meetings. Although they both embraced the expanded role to help students succeed during this difficult time, they said that the more frequent and instantaneous access could be tiring, particularly as they pursue their own graduate work and deal with their personal situations. “It’s been more difficult in that respect,” Lachner said. “We are in a situation that’s kind of nonstandard, so you kind of have to roll with it.”

THE REMOTE CLASSROOM

The move to online classes was more seamless for some than others. Jud Partin, a research associate with the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics (UTIG) who teaches an advanced statistics class for graduate students, had already introduced Zoom meetings in 2019 as a way of bringing together students based at different UT campuses.

However, there are still reminders that these are far from normal times. Partin’s class now includes occasional interruptions from his 4-year-old. “Fortunately, everyone’s quite forgiving these days,” Partin said.

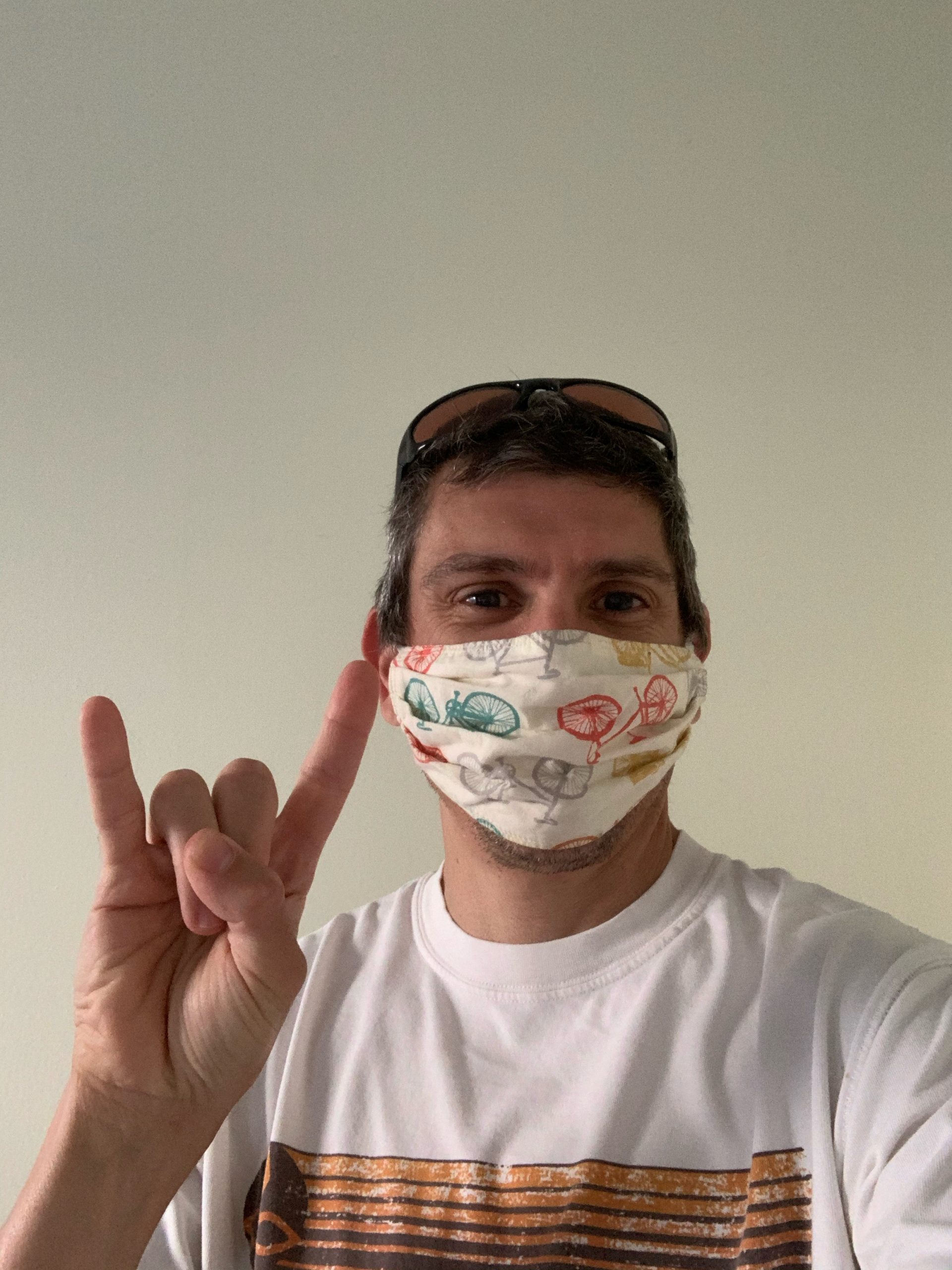

Other classes presented more difficulties. In field methods, the class went from traversing outcrops themselves to controlling an avatar in a virtual field experience that resembled a computer video game. In the virtual field, students still had to make maps and generate a geologic history. But collecting the data from outcrop entries in a digital field notebook just wasn’t the same, said Barbara Sulbaran, an undergraduate who took the course during the spring. “I can’t physically look at the rock. All of what you’re supposed to do is already done,” she said. “I love my field notebook, and I haven’t had to look at it [since quarantine].”

And in large lecture classes, connecting with students through a screen proved to be a challenge.

Assistant Professor Daniela Rempe and Professor Richard Ketcham were co-teaching Introduction to Geology when the course first shifted to online learning during the spring. About 115 students should attend each lecture, but online only about 40 to 50 showed up — a number that Rempe said she was fairly happy with given the situation. The course was conducted over Zoom and blended prerecorded lessons with real-time discussions and interactive exercises. And while Rempe found that students were quick to use the chat function to ask questions during class — a nice change from the large lecture halls where it was rare for students to raise their hands and pose questions — hardly anyone would turn on their cameras or microphones. Rempe was left addressing a screen of dozens of blacked-out little boxes.

“Maybe they are on their phone or maybe they don’t want us to see where they live,” Rempe said. “It’s hard to say why they do that, but that part has been very frustrating.” With guidance from UT leadership, the Jackson School spent the summer developing two plans for teaching during the fall semester. The first plan prioritized face-to-face learning. The second plan was a hybrid model in which online classes were prioritized while still allowing for classes that blended online and in-person learning, as well as a small number of only in-person classes.

In early June, when the coronavirus infection rate had plateaued in Austin, there were high hopes that the fall semester would mean in-person learning for most everyone, said Charles Kerans, the chair of the Department of Geological Sciences. However, a spike in COVID-19 cases in early July finalized the decision to prioritize online learning. This fall, about 56% of Jackson School classes — 30 out of 53 — are being taught exclusively online. Almost all the rest are available as two options: online or hybrid courses that blend in-person and online learning.

Introduction to Geology — the same class that Rempe and Ketcham taught entirely online during the spring — is now a hybrid course and taught by Associate Professor Tim Shanahan. Usually, the course would be capped at about 250 students, the maximum capacity of the Jackson School’s largest lecture hall, the Boyd Auditorium. But online learning has allowed the course to take on more than double that amount. The 550 total students currently enrolled across the two class sections is a record breaker.

“It’s nice to see there’s so much interest in geology, and the feedback I’m getting from students is that they’re really excited about it,” Shanahan said. “But teaching on Zoom, when you look down and see that you’re at like 275 people is a little bit crazy.”

Shanahan said that students are still hesitant to turn on their cameras and microphones. He faces the same screen of black boxes as Rempe. But he is working to promote engagement in other ways. He changes the Zoom background to match the lecture material. (For introductions on the first day of class, Shanahan, a paleoclimatologist, opted for a photo of him and graduate students taking a sediment core from a lake.) He also streams music from the class Spotify playlist, which was started by Rempe, as students log in for lectures. Sometimes he plays student requests. But he can’t resist matching the song to the lecture when the opportunity arises. A lecture on continental drift started with Sia’s “Unstoppable.”

Shanahan has also made a point to check in with the freshmen in the class at the start of the semester, organizing smaller Zoom sessions of about 20 people to answer questions and provide guidance. He is hosting similar sessions with international students, who face their own unique challenges, such as making sure they can take an exam at a decent hour in their time zone.

HANDS-ON LEARNING NEAR AND FAR

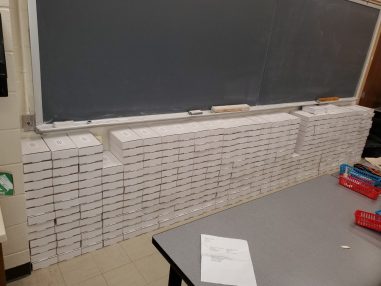

During the spring, the quick shift to online learning meant that students enrolled in Introduction to Geology did not have access to rock and mineral specimens that they would usually examine in the course’s lab sections. They made do by studying structure and faulting with paper models. This fall, making sure that remote and socially distanced learning still included real rocks was a top priority. The Department of Geological Sciences ordered a total of 632 custom rock kits — each containing 30 specimens — for every student enrolled in Introduction to Geology and Physical Geology. Students taking the course entirely online had their kits mailed to them, with some kits going as far as Saudi Arabia. To offset the $60 cost of the kits, Shanahan wrote the lab manual for the courses and provided it to the students for free.

Earth Materials is one of the few classes with an in-person option available for both lecture and lab, along with online and hybrid options. For some classes, students bring rocks and minerals from the lab to lecture in plastic containers. The course instructor, Associate Professor Elizabeth Catlos, also has larger samples — which she disinfects with a generous spray of Lysol before class — arranged on a table at the front of the classroom.

“If this course was offered only 100% online, I think the students would have a huge disadvantage,” Catlos said. “They are taking a field class after this, so how do you do a field class without working with hand specimens first?”

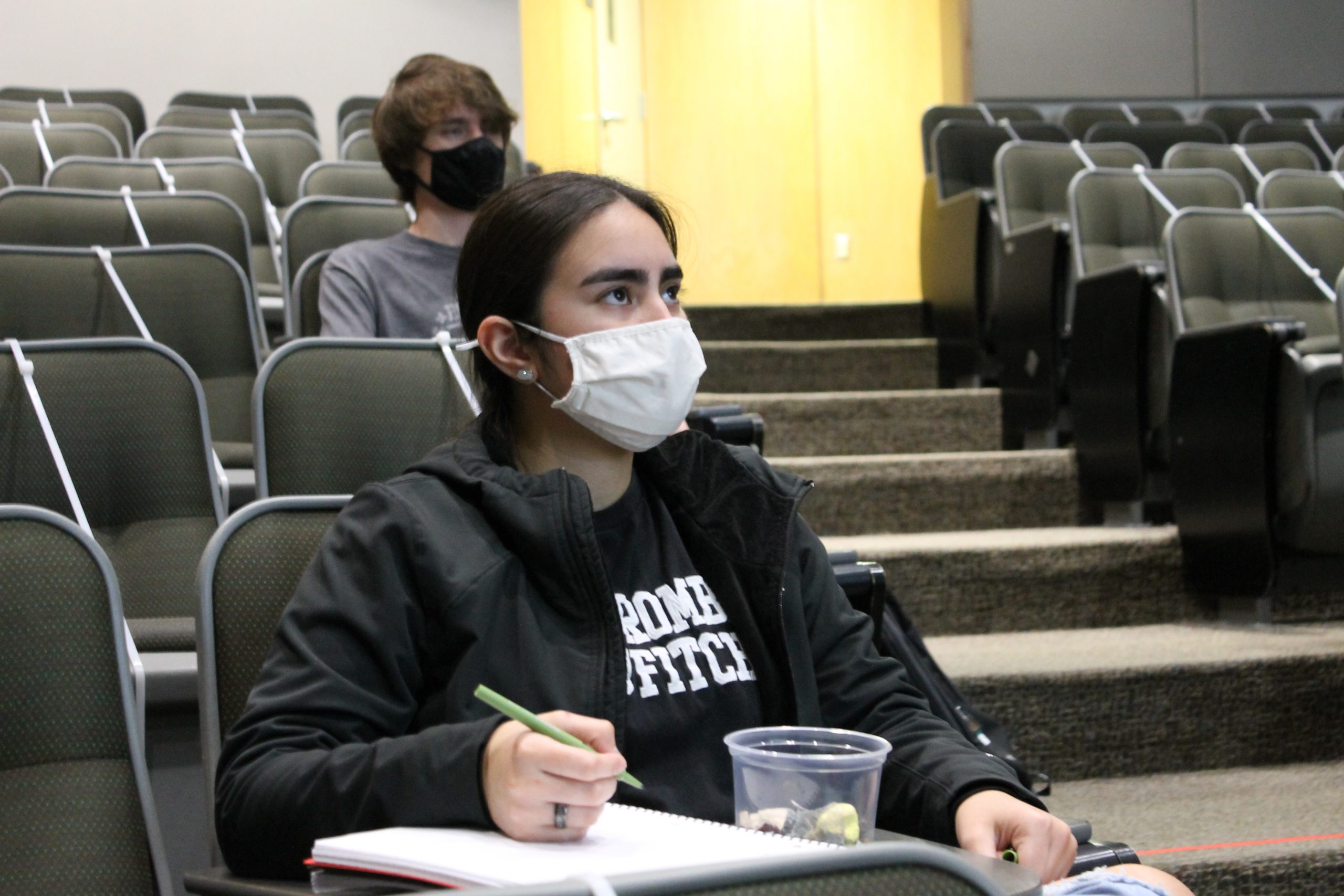

The in-person class meets in the usual lecture space of the Boyd Auditorium, but with a number of safety precautions in place. Most of the seats are zip-tied closed, leaving only socially distanced spaces available. Arrows on the floor mark walkway directions. Two poster displays at the front and the back of the room serve as cleaning supply caddies. And everyone wears a face mask, with Catlos opting for a clear plastic one when she is lecturing so students can lip-read and see her facial expressions.

For the course’s in-person lab, maintaining social distancing has required students in the same lab section to be split up across two classrooms at opposite ends of a hallway. At first, this presented a problem because a sole teaching assistant teaches the lab. But installing a digital doorbell between the classrooms has proved to be a quick fix, Catlos said. Students simply ring if they need to call the TA for questions or need help.

The doorbell is a creative solution to a less than ideal situation. The ultimate goal is to have classes where everyone can be together again someday. However, some of the technological workarounds have, in some cases, proved to be advantageous over in-person learning. Like Rempe, Shanahan has noticed an uptick in student questions using chat. And Associate Professor Daniel Breecker, who livestreams his Physical Geology class from a classroom turned recording studio, said that he is planning on bringing the digital polling he has integrated into his remote lectures back into the classroom with him, whenever that may be.

“In person, you ask a question but only one person will answer. So this actually is an improvement,” he said. “This is an opportunity to try out some stuff and see what I like and figure out how to incorporate it into the class when all this is over.”

RETURN TO RESEARCH

When UT shifted to online learning in March, laboratory and fieldwork were put on pause. Some projects were able to adjust to remote work. Assistant Professor Tim Goudge is still studying Martian geology using remote sensing data from satellites. And during the spring, doctoral student Omar Alamoudi made good progress on building a machine for rock physics experiments in his home office.

But for many Jackson School scientists, getting back to research meant getting back to the lab. At the Department of Geological Sciences, Associate Dean for Research David Mohrig led the charge to do so safely. The school quickly put in place a rotating schedule for researchers to keep lab density low, and a check-in system to keep track of people in case of the need for contact tracing. (So far, there have been no cases of coronavirus spread tracked back to laboratory work). Within two weeks of the university’s closing, 20 researchers were able to return to the lab. By August, that number was 360, about 80% of the school’s research staff.

For the fall semester, research and classes are being kept completely separate, Mohrig said, a setup that can potentially keep research going even if all classes shift to remote learning again.

“If the classrooms have to close again, the research can continue,” Mohrig said. “We don’t have to rebuild that enterprise.”

The Jackson School’s two research units, the Bureau of Economic Geology and UTIG, are abiding by similar research protocols as the department. Most of the bureau’s 15 labs are up and running, along with its core research center, which has set up socially distanced core-viewing areas. At the institute, most research is able to continue remotely. However, the field missions and scientific cruises on which much of the raw data is collected have been put on hold.

Local fieldwork has resumed on a case-by-case basis. Bureau researchers are maintaining TexNet seismometers across the state. In late July, graduate student Chris Linick travelled to the McDonald Observatory in West Texas to repair a gravimeter (See page 75). And although two of the Jackson School’s field camps were canceled during the summer, the school’s capstone field geology course, GEO 660, continued — but in a scaleddown, socially distanced form. (See page 68).

Kerans is continuing to bring Jackson School students into the field this fall as part of his course on carbonate and evaporite depositional systems. He opted for a field setting for the course’s labs, which is better suited than the classroom for social distancing — and for fresh air, he notes. Although field research overall has been scaled back, when it comes to sharing research results, going remote has been a boon for lectures and seminars.

Catlos said that the Jackson School’s DeFord Lecture Series has undergone a revival of sorts now that they’re streamed over Zoom and open to the public. Attendance at recent talks has been about 200 people, with scientists from across the world tuning in.

Zoom seminars at the bureau and UTIG have also seen a bump in attendance. And according to the latest cohort of doctoral students, presenting their dissertations over Zoom enabled more people to attend — from friends and family, to research collaborators, advisers and even potential postdoctoral research collaborators.

“It was really nice to be able to invite people that I would like to work with,” said Chelsea Mackaman-Lofland, who earned a doctorate in April.

LOOKING AHEAD

Thomas Quintero finished his final semester at the Jackson School in the spring.

Like many students, he was able to go home to his family to finish the semester. Between his senior thesis, finishing classes and helping his older brother renovate a home he just bought, it was a busy end to the semester. In all honesty, he said, he was ready for school to just be over so he could focus on the next phase of life.

Nevertheless, he was glad he could close out his college career with a graduation ceremony. He wasn’t able to walk across a stage. But he was able to gather with close family to watch the Jackson School’s virtual commencement ceremony. Quintero said that they paused the video to take pictures in front of the slide that listed his name alongside Bachelor of Science in Geological Sciences.

“I’m thankful there was something,” said Quintero, who is now putting his geology degree to use as an intern at an organization that is using geospatial analyses to determine where water capture systems should be built in Detroit, Michigan, neighborhoods so residents’ drainage fees can be reduced. He plans to attend graduate school later on.

Remote and socially distanced learning has changed everything this year — from introductory geology classes to graduation. Although it’s hard to say how long it will remain the norm, the Jackson School community is working to constantly adapt, improve and remain resilient to a whole new way of being geoscientists.

The University of Texas at Austin

Web Privacy | Web Accessibility Policy | Adobe Reader