Science at Sea

GRADUATE STUDENTS PULL DATA FROM THE DEPTHS ABOARD SEISMIC CRUISES

BY JESSICA HALL

Kelly Olsen spotted dolphins for as far as the eye could see off the coast of Chile in 2017 while aboard the R/V Marcus G. Langseth. But while the Jackson School of Geosciences graduate student was excited to see the animals, she was disappointed too. The proximity of the protected marine species meant the end of data collection until the dolphins left the area. She would have to wait to gather data for her thesis — how the incoming sediment off Chile influences the development of powerful earthquakes — another time.

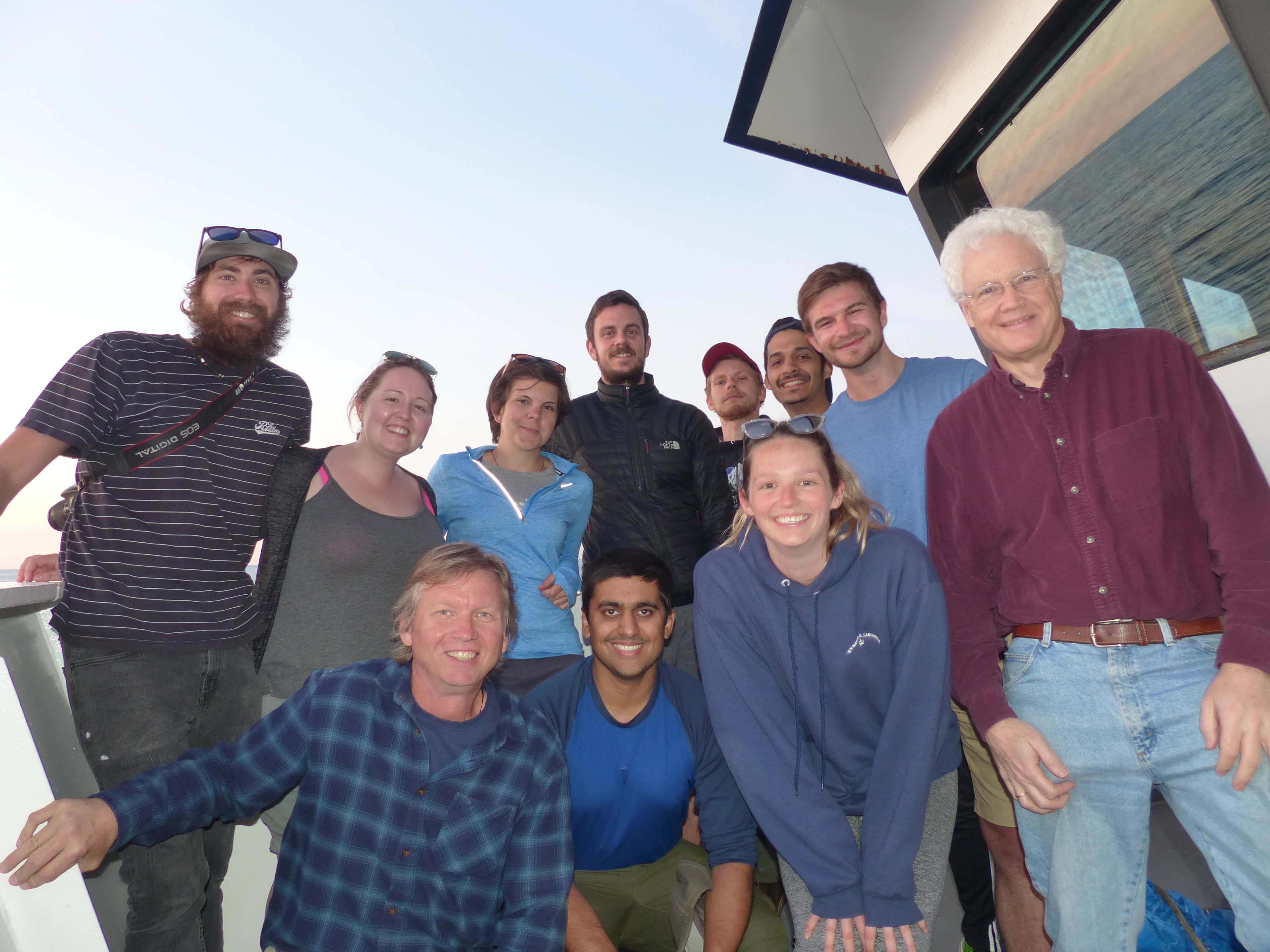

This story is familiar to Jackson School graduate students conducting research with the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics (UTIG), a research unit of the school. Over the last few years, students have had many opportunities to take part on research cruises, from Chile to Alaska to New Zealand.

This research is essential for improving scientists’ understanding of earthquakes and tsunamis. For instance, why do earthquakes in some places — like Chile — happen quickly with great force, but in other places — like in New Zealand — occur very slowly over an extended period of time in what’s known as “slow slip events?” These research cruises are imperative to understanding how our world works and helping those that live in areas impacted in earthquake zones.

The Jackson School provides opportunities for students to gather this data themselves, helping create the foundation of their scientific careers whether in academia or industry. Participating in field research allows them to learn about data collection, meet people from around the world and develop leadership skills.

“It’s important to see the entire process, for collecting and then processing the data,” Olsen said. “It gives me insight into how data sets are collected and the uncertainties.”

Unlike industry cruises, research vessels like the Langseth allow plenty of opportunities for students to have a first-hand experience in the data collection and processing, working side-by-side with lead researchers and the ship’s technical and operational crew during the often six-week long experience.

Most recently, students took part in three cruises conducted off the coast of New Zealand from October 2017 to January 2018, taking advantage of the Langseth’s schedule in its waning years of operation. (The research vessel is slated to end operations in 2020.) The missions were dubbed Seismogenesis at Hikurangi Integrated Research Experiment (SHIRE), Hikurangi 3D and South Island Subduction Initiation Experiment (SISIE).

Research Professor Sean Gulick, the co-principle investigator of the SISIE mission, explained that bringing students aboard helps build them into better geoscientists.

“I think it’s critical for students to have the field experience,” Gulick said. “It is part of what makes us geoscientists; it’s an observational science.”

COLLECTING DATA

For the students, being aboard these cruises gives them insight into how to use the various equipment, including ocean bottom seismometers, airstream guns and multibeam sonar.

“It’s eye opening to see how much work goes into collecting the data and why it’s so expensive,” said graduate student Andrew Gase. “A lot of people have put a lot of work into these data sets and don’t get recognition for the work they’ve done.”

Students are studying everything from the development of megathrust earthquakes, to failure of lithosphere and tectonic history, to the changes in physical properties and structures of oceanic crust. By using various means of data collection, they are able to have more information to interpret and better understand how earthquakes are happening and how the structure of our planet comes into play.

Dominik Kardell, a graduate research assistant, had spent very little time in the field prior to the SISIE cruise this January in New Zealand. He described the cruise as an unparalleled learning experience.

“One of the things I knew very little about was how some of the scientific instruments worked and how to use them to efficiently collect geophysical data,” Kardell said. “My eyes were opened towards many research components that successful scientists need to be able to manage.”

On the SISIE cruise in January, the team came across two named storms and had to seek shelter behind an island, delaying work by days. The five primary investigators were constantly in communication with each other and the crew. And while they were ultimately successfully in gathering the data they required, hard decisions were being made every day, Gulick said.

Involving students in those decision making discussions was a priority, he said. Learning how to collect data means also knowing when to stop data collection for safety — for those aboard the ship and the instruments.

“Decision making skills are a critical part of being a scientist,” Gulick said. “Doing that under pressure is part of the job, it’s exciting to see it being done in front of you and maybe advising.”

LIFE ONBOARD

As Andrew Gase explained, being onboard a research cruise is a lot like Groundhog Day. Each person on the ship is assigned a shift, and that is when they work every day for the duration of the cruise. And in wide-open ocean, the scenery doesn’t change much.

A typical day includes:

• Breakfast

• Shift work (either in the lab or as a watcher on deck)

• Down time (typically spent napping, reading, exercising or

processing data)

• Lunch

• Shift Work

• Down Time

• Dinner

• Sleep

A key thing to remember is that the research is happening around the clock, so breakfast could be at lunchtime or dinner time depending on the time you were assigned. Graduate student Brandon Shuck said he made sure to do one thing on each of the two cruises he was on last year.

“I tried to watch as many sunrises and sunsets as I could,” he said. “On SHIRE I saw sunset every night. And on SISIE it was sunrise every morning.”

This helps break up the monotony of day-to-day life on the cruise, Shuck said. Senior Research Scientist Nathan Bangs shared a few other tips to help with the monotony.

“Patience, keep your eyes open, and talk to people,” he said.

LOOKING TO THE FUTURE

Research cruises are building up what scientists know about how earthquakes happen. The knowledge doesn’t stop there, though. It’s essential data for real-world applications that seek to protect people from devastating events, like early warning systems for earthquakes and tsunamis.

“Our career depends on collecting high quality images of the earth, and it depends on the next generation to know how to collect it,” said Gulick. “We want to instill in [students] the excitement and attention to detail that has to occur at sea so what you come home with will satisfy the science questions and move the science forward.”

And that’s just what they are doing. Each student expressed an interest in continuing to go into the field and conduct research, whether their own or to help fellow scientists. Olsen recently went to Alaska to gather data aboard a different research vessel for the added experience. And other students described it as invaluable for their own career plans, which include both academia and industry. But to Gase, the fact that the data could have a life beyond his own projects is what makes collecting it so worthwhile. What he finds could play a part in advancing research and helping others.

“It’s cool to go in field and work on big projects,” he said. “It’s going to be used by people for decades.”

The University of Texas at Austin

Web Privacy | Web Accessibility Policy | Adobe Reader