Rapid Response

Jackson School Researchers Study Aftermath of Hurricane Harvey on Texas Gulf Coast

BY MONICA KORTSHA

When Hurricane Harvey hit the Texas coast about one year ago, the Bureau of Economic Geology’s Jeff Paine was ready.

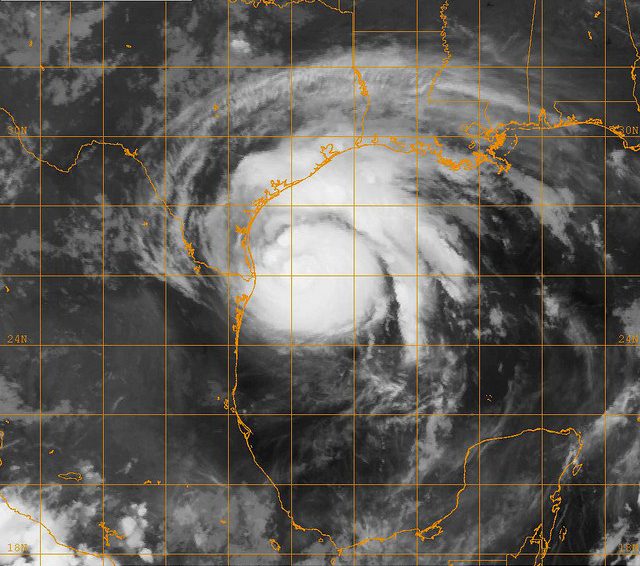

Paine, the coordinator of the bureau’s Near Surface Observatory, had been watching the storm since it was just a tropical wave in the Caribbean. When it rapidly gained strength while approaching the Texas coast — turning from a Category 1 to a Category 4 hurricane in less than 24 hours — he knew that there would be damage to the state’s beaches and barrier islands, home to coastal communities, robust businesses, busy ports and rare bird rookeries.

While first responders and regular Texas residents alike sought to help people directly affected by Harvey — from the flooding in Houston to the wind-damaged homes of Port Aransas and Rockport — Paine began discussions about surveying the damage from the air with the General Land Office (GLO), the state agency that manages the state’s coastal lands. By the following Thursday,researchers from the bureau’s observatory were airborne.

“Within a week of landfall we were out acquiring imagery and topographic data,” Paine said. Geosciences were probably not on most people’s minds in the wake of Harvey. But the days and weeks after a hurricane are a vital time for collecting field data about its impact. This data not only records the extent of the damage but can also hold clues about how the coast is expected to recover and what communities can do to prepare for future storms. Paine’s survey was just the start of this collection process for scientists at the Jackson School of Geosciences, with three research teams — one from each of the school’s research units — heading out shortly after the storm to conduct field work. Thanks to the Jackson School’s Rapid Response Program, they were all able to gather the resources and equipment they needed to get to the coast fast.

"Collecting data early doesn’t help if you can’t get it out to anybody for them to use."

– Jeff Paine, Bureau of Economic Geology

Time was of the essence. With every passing day, evidence of the hurricane was starting to disappear, smoothed away by waves and wind or removed by communities on the mend. Disappearing with them would be valuable information about the potential lingering effects of the storm on beaches, wetlands and the state’s narrow string of barrier islands — a delicate system that forms the first line of defense against powerful storms such as Harvey.

After the Storm, Into the Field

The Rapid Response Program was created with speed in mind. The program funds fieldwork in the aftermath of natural disasters — research that is vitally important for understanding nature’s most powerful forces and their effects on the environment and society, but understudied because of the logistics of funding research on the fly, especially in disaster areas.

The program sent Jackson School scientists to the Philippines to measure aquifer contamination after Typhoon Haiyan struck in 2013, to New York in 2012 to study signs of coastal erosion in the wake of “Super Storm” Sandy, and to the Texas coast in 2008 to study seafloor changes after Hurricane Ike.

After Harvey, the Jackson School quickly mounted a multipronged research mission that leveraged the expertise and resources of its research units.

Paine’s mission was the first to take to the coast. Supported with funds from the GLO and the Rapid Response Program, he and a team of scientists from the Near Surface Observatory captured changes from the air using high-resolution photography and LIDAR, an imaging technique that uses an array of laser beams to measure landscape elevation. From early September through October, they surveyed the entirety of the Texas Gulf shoreline — flying from South Padre Island near the mouth of the Rio Grande to Sabine Pass along the Louisiana border — pausing only for an exhaust pipe replacement and on days when Gov. Greg Abbott or Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick called dibs on the state-issued plane.

“The moment the storm passes, recovery begins.”

– Jeff Paine, Bureau of Economic Geology

he survey was able to start only days after the storm in part because of lessons learned from Hurricane Ike, said Daniel Gao, a geographic information specialist at the GLO. After Ike, the office relied on LIDAR data collected by the U.S. Geological Survey. Gao said the LIDAR data proved so important after Ike that the GLO wanted to ensure it had a system set up to quickly and accurately gather data after the next storm.

“It was after [Ike] that we were in talks with the BEG where we asked them, ‘If something like this were to happen again, could we quickly get elevation data from LIDAR?’” Gao said.

Harvey was the first chance for the team to put the plan into action.

Paine’s initial GLO flights focused on quickly getting images of the Port Aransas area where Harvey made landfall back to the state so workers could assess the damage and plan cleanup and recovery efforts. These flights zeroed in on beaches and dunes, shipping channels in bays, and coastal bird rookeries, with data from each new flight being added to a digital map operated by the GLO to help guide on-the-ground assessment.

“Collecting data early doesn’t help if you can’t get it out to anybody for them to use,” Paine said. “So we had next-day delivery.”

Although the GLO-funded surveys eventually spanned most of the Texas coast, they didn’t cover San Jose Island and Matagorda Island, the two barrier islands just a few miles offshore that took a direct hit from Harvey. All of San Jose Island and a portion of Matagorda Island fall outside of the state’s emergency response purview, explained Kevin Frenzel, a Jackson School alumnus who now manages the GLO’s Coastal Erosion Planning and Response Act program.

“The fact that they’re not publically accessible means that the GLO doesn’t have authority for a response,” Frenzel said. “San Jo (San Jose) is also a private island, so we can’t expend public money on a private island.”

Nevertheless, the islands are an essential part of the state’s coastal well-being, shielding the coast from the brunt of hurricane impacts and creating coastal channels that guide shipping barges to Texas ports.

“The islands protect everything [along the coast], refineries, communities, fisheries,” said doctoral candidate John Swartz, who participated in the Rapid Response missions. “Understanding how they’re built up and destroyed is really important.”

With Rapid Response support, the Jackson School teams turned toward discovering what happened to the barrier island system when Harvey arrived, with Paine’s team collecting data on the islands from the air and missions led by the other units documenting damage from land and at sea.

John Goff, a University of Texas Institute for Geophysics (UTIG), senior research scientist, took to the coast in September to lead a four-day seafloor mapping survey of Lydia Ann Channel and Aransas Pass, and collect data on how the storm affected coastal sediments — the raw material that builds up barrier islands. Goff’s team included Research Science Associates Marcy Davis and Dan Duncan, as well as Swartz.

And in October, Associate Dean for Research David Mohrig, a professor in the Department of Geological Sciences, led a survey of Sargent Beach and the Matagorda Peninsula, a barrier-island peninsula to the east of Matagorda Island proper.

During the three-day mission the team studied sand and sediments on land, digging trenches to document the history of sediment deposition and tracking how fans of sediment deposited by the storm surge sprawled across the island. Mohrig’s team included Ph.D. candidates Benjamin Cardenas, Kathleen Wilson and Swartz; postdoctoral researcher Eric Prokocki; and Jackson School undergraduates Arisa Ruangsirikulchai, Matthew Nix and Mitchell Pham.

The barrier islands and coastal communities faced Harvey’s 130 mph winds and storm surge. But what set Harvey apart from other hurricanes — and what made it so destructive — was the days-long deluge it dumped on Houston and the surrounding areas. The rain led to flooding across the area, killing dozens by drowning and causing the majority of Harvey’s estimated $125 billion in property damage, according to the National Hurricane Center.

The rising waters also had a geological effect, sweeping up sediments and moving them to new places with the flow of the current. To document this part of the storm, Ph.D. candidate Hima Hassenruck-Gudipati ventured into the field in a canoe to conduct a Rapid Response mission of her own.

“It’s not storm surge, it’s not coastal erosion, but it’s important nonetheless because when Harvey made landfall, it brought all this moisture,” she said.

The mission site was a floodplain in Liberty, Texas, about 40 miles east of Houston. Hassenruck-Gudipati had been monitoring the area for her doctoral research on sediment transport, placing game cameras in trees to track the rising waters during the area’s frequent flood events. Harvey dropped 55 inches of rain in the Liberty area, inundating the plain and causing the nearby Trinity River to overflow its banks. When Hassenruck-Gudipati arrived about a week after Harvey’s landfall, the water was still moving swiftly across a plain dotted with debris.

“The water on the floodplain was moving faster than what we were expecting, so it took some courage to be like ‘OK, let’s just go for it,’ ” Hassenruck-Gudipati said.

She and two field assistants, Timothy Goudge, then a postdoctoral researcher and now an associate professor, and Katja Luxem, a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Geosciences at Princeton University, spent two days on the scene, piloting the canoe through the floodwaters and collecting data on current speed, a key variable for estimating the size of sediment moving through the water and how far it could be deposited on the plain once the water subsided

Harvey by the Numbers

From the floodplain to the coast, the Rapid Response missions documented Harvey’s geological impact on Texas, with the data collected by each unit working together to tell a larger story on the aftermath of the storm. Along the barrier island system, that story centered around erosion. Harvey’s storm surge stripped away massive amounts of sediment from island beaches and carried it into the ocean.

According to the bureau’s LIDAR data, Harvey eroded the 21-mile-long shoreline of San Jose Island, removing sand up to 125 feet inland and eliminating 13 feet of dune elevation in the process. On Matagorda Island, the erosion reached 75 feet inland along the 38-mile-long shoreline and eliminated three feet of dune elevation. The storm brought a similar fate to the shoreline of the Matagorda Peninsula, flattening the beach to a near uniform level.

On San Jose Island, erosion from the storm also cut a series of inlets that sliced up parts of the Gulf side beach. However, rather than being formed by water lashing onto the shoreline, the inlets appeared in satellite imagery to be carved by water actually flowing over the top of the islands from behind. The water was initially pushed through existing channels and passes by the hurricane, built up in the bays and estuaries behind the barrier island, and then topped the island as it returned to sea, with the counterclockwise rotation of Harvey’s winds providing a push.

“The water was pushed right out of Port Aransas,” said Goff.

A computational model of Harvey’s storm surge created by Clint Dawson, a collaborator of Goff’s at the university’s Institute for Computational Engineering and Sciences, helped confirm that theory, as did on-site analysis of beach sediments conducted after the initial Rapid Response missions. But perhaps the clearest evidence for outflow creating the inlets came from three large shipping barges stranded on the Gulf side of the island after the storm. A satellite image taken months earlier shows those same barges secured to mooring posts in Lydia Ann Channel, the shipping channel that runs along the mainland side of the island.

It’s normal for barrier islands to lose large amounts of sediment during hurricanes, Paine said. The factor that will influence the long-term integrity of the barrier islands is whether that swept-away sediment can make its way back to shore.

According to the offshore seismic data collected by UTIG researchers, the fate of sediments that were swept into the sea is uncertain. Signs of seafloor erosion in Lydia Ann Channel and Aransas Pass indicate that the hurricane’s storm surge exited the waterways at high speed, sweeping away large amounts of sediment from the islands and into the Gulf. And at Aransas Pass, two jetties that extend the natural reach of the channel may have exacerbated the loss of sediment by acting like the nozzle of a hose — concentrating the fast-flowing water and shooting it out to sea.

RATES AND SEDIMENTATION ON SAN JOSE ISLAND.

“Without the jetties, the sand could have just been deposited [outside the channel],” Goff said. “The jetties channeled the sediment offshore.”

Offshore sediment can still make its way back to the barrier island system. However, if it happened to venture beyond a point known as the “depth of closure,” the sediment exits the coastal system completely and is unlikely to return. The exact values for determining the depth of closure are still up for debate. However, Goff hopes to learn more about where the sediments went— and whether they might come back— by collecting core samples offshore of the barrier islands.

Whereas the coastline lost sediments, the floodplain near Liberty was a different story, with the floodwaters taking material from the Trinity River and depositing it across the plain.

Hassenruck-Gudipati’s research revealed that the floodwaters maintained high enough speeds for long enough to spread sediment thousands of feet away from the river banks.

“We thought that any sedimentation would happen locally near the banks, not a half kilometer from the bank,” said Mohrig, who is Hassenruck-Gudipati’s Ph.D. adviser.

The data showed otherwise, with the water moving quickly enough to leave deposits in the middle of the floodplain once the water dried up. Over time, this process may influence the lay of the land and affect what areas around Liberty are susceptible to future floods.

In addition, Hassenruck-Gudipati notes that sediment distribution is a good indicator for how other substances, from nutrients to synthetic chemicals, can be transported throughout an environment during a flooding event, information that could prove useful to studying how hazardous materials might have spread through the Houston area.

The data collected by the Rapid Response missions are a baseline that researchers and policymakers can use to gauge Harvey’s effects and are already proving useful to long-term recovery efforts coordinated by the GLO, said Frenzel.

The LIDAR survey data documenting erosion on the coast is helping the agency apply for federal grants for beach renourishment projects, which bring new sand supplies to eroded coastlines. The renewed beaches help bolster the coastline’s resiliency to future storms, Frenzel said, as well as recharge the local economies that took a blow from the storm.

“Our cost benefit for beach nourishment range that for every $1 spent, we get a return of $6 to $8,” Frenzel said. “That’s a heck of a return on investment.”

The Rapid Response results are also helping Jackson School scientists conduct basic research on the geoscience of storms. In particular, findings from the mission led by the department’s David Mohrig are revealing how far-afield events can prime beaches for erosion when hurricanes such as Harvey strike.

Coastlines Unzipped

There’s a theory in sedimentology that when a hurricane disturbs sand and sediment along a coast, that initial disturbance makes the coastline more vulnerable to more erosion. Unsettled sand grains are simply easier to move.

“Once you’ve had a big erosion event and liberated a lot of sand that makes the coastal deposit, it’s much more susceptible to future reworking by subsequent storms that happen in fairly short order,” Mohrig said. “You sort of unzip it.”

The theory makes sense conceptually, but according to Mohrig, there’s little field data to show just how much more easily erosion happens after an initial hurricane strike. An unusual sediment fan observed by Mohrig’s team on Sargent Beach is helping to show how this “unzipping” process works and what forces can influence it.

Sediment fans are deposited during storm surge events, with the sediments recording how far inland the storm surge reached. The team expected to find an uninterrupted swath of sediments left by Harvey. Instead, they found that the fan contained breaks and areas where the deposits doubled in thickness. When the team dug a trench into the sand to get a better read of the depositional history of the beach — with each sedimentation event recorded as a distinct layer — the break appeared there in the form of a dark layer made of material much smaller and finer than the surrounding layers.

“That break left us scratching our heads and wondering what caused it,” said Kat Wilson, a Ph.D. candidate who took part in the mission.

The researchers initially attributed the breaks to Harvey’s surge receding and advancing at different points during the storm. However, aerial photos of the fan collected by Paine’s mission combined with data on wave energy off the coast during the weeks after Harvey suggested a different story: Hurricane Nate and Hurricane Irma — two storms that didn’t make landfall on the Texas Gulf Coast — were nevertheless still able to disturb sediment on its beaches. The storms even generated about as much wave energy as Harvey, though over a much shorter period.

Wilson notes that under different circumstances, the waves generated by Nate and Irma wouldn’t have disturbed the beach at all. But the erosion caused by Harvey, which flattened the beach and disturbed sediments, allowed the waves from the far-away storms to wash over the shoreline and leave deposits of their own.

“The coast was already damaged and still in the recovery phases,” Wilson said. “So distant storms can definitely cause an outsized effect to the coast than what otherwise would happen.”

Mohrig said that the Rapid Response findings illustrate how effects from one storm can influence the damage done by others. The sedimentary record uncovered in the trench has inspired his research team to look for signs of more storm interactions for past events, including Hurricane Ike and Hurricane Ida, and how erosion and deposition linked to hurricane events influence the coastal landscape over time.

“This is the most interesting thing to report scientifically, this idea that you can remobilize these things by far-afield events,” Mohrig said. “When we think about our coast being hit by big, eroding storms, we have to think more broadly than we often do. Other storms in the Gulf can do a lot of damage — particularly if there’s been a previous storm.”

Building on Knowledge

It will take years to understand the longterm effects of Hurricane Harvey on the Texas Gulf Coast. The data retrieved by the Rapid Response missions will be an important starting point for evaluating how the coast is recovering, and what actions the state can take to prevent damage from future storms.

“Very rarely have data like this been collected so early,” Paine said. “We have good data for what the conditions were like right after the storm. And that’s really critical because the moment the storm passes, recovery begins.”

But the Rapid Response data is just part of what makes the analysis possible. The researchers were able to put their findings in context thanks to consistent monitoring of the coast by the Jackson School and state and federal research organizations.

"The reports and data we get from the [BEG] are just spot on. It's a big asset that we have the university here."

– Kevin Frenzel, General Land Office

Paine compared his group’s LIDAR data with surveys conducted by the Army Corps of Engineers in 2016; Hassenruck-Gudipati had been monitoring the site in Liberty for months prior to Harvey; and Goff’s baseline data for the seafloor surveys came from channel surveys collected in 2009 and 2012 by Jackson School students during their Marine Geology and Geophysics summer field courses.

Together, the data are helping Jackson School scientists evaluate the aftermath of the storm. It will take ongoing research to determine the storm’s long-term effects and what should be done to mitigate them.

“It’s hard to know at this point how much permanent damage was done,” Paine said. “Material will be coming back to the beach and dune system within weeks, months and years after the storm.”

Having data collected in the wake of the storm — when dunes were flattened, channels were scoured, and a flood plain was still filled with water — will make this future data even more meaningful.

Frenzel, the geologist from the GLO, said the Rapid Response data from the bureau will be key in informing how Texas will rebuild.

“The reports and data we get from them are just spot on,” Frenzel said. “It’s a big asset that we have the university here.”

Rebuilding is just part of the process. According to Mohrig, the Rapid Response missions kicked off research on the state’scoastlines that will last for hurricane seasons to come.

“We’ll be monitoring how recovery happens,” he said.

The University of Texas at Austin

Web Privacy | Web Accessibility Policy | Adobe Reader